How Return of the Obra Dinn refreshes the nautical disaster tale

Taking the puzzle game by storm

Warning: contains spoilers.

When Ernest Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, was trapped in unyielding ice, it was clear the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition had taken a bad turn. In late 1915, after months of anxious waiting, the sheer pressure of the ice crushed the most advanced ship of its time “like a nutshell”, according to captain Frank Worsley. Stranded on the ice for ten months, the entire crew, battered but alive, was eventually rescued. Far less lucky was the crew of the whaleship Essex, which sank in the middle of the Pacific after a sperm whale attack in 1820. When the few remaining survivors were rescued months later, they were sucking the bone marrow from what remained of their fellow sailors.

The crew of the Obra Dinn share a similarly morbid fate.

Lucas Pope’s new game is all about uncovering the myriad deadly accidents that took place aboard the ship. It draws on stories like those of the Endurance and the Essex, and adapts them to build a puzzle game around them. From Robinson Crusoe and Moby Dick to this year’s The Terror, there is something about nautical disasters which is oddly irresistible to landlubbers and makes them perfect raw material for spinners of yarn. That old favourite, the theme of ‘man versus nature’, goes some way towards explaining it, but there’s still greater depths to plumb.

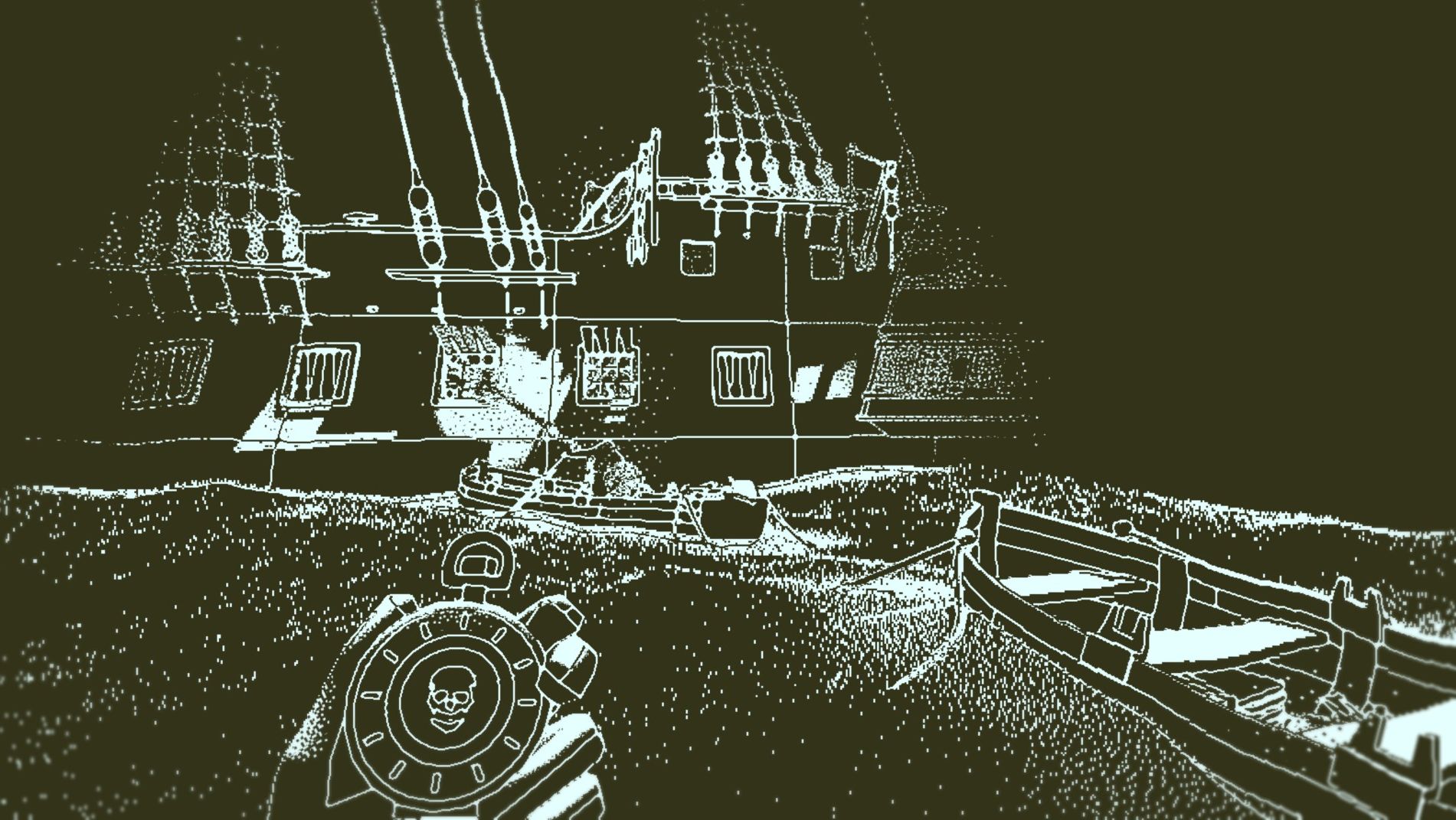

Most sea-faring games, from Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag to Sunless Sea, look at the ocean’s expanse with spyglass-induced far-sightedness, drawn to distant locations beckoning like lighthouses. Very few look to the ship itself as their actual setting. Obra Dinn is a rare exception and makes great use of its compact space in a way that shows deep understanding of the appeal of nautical disaster stories.

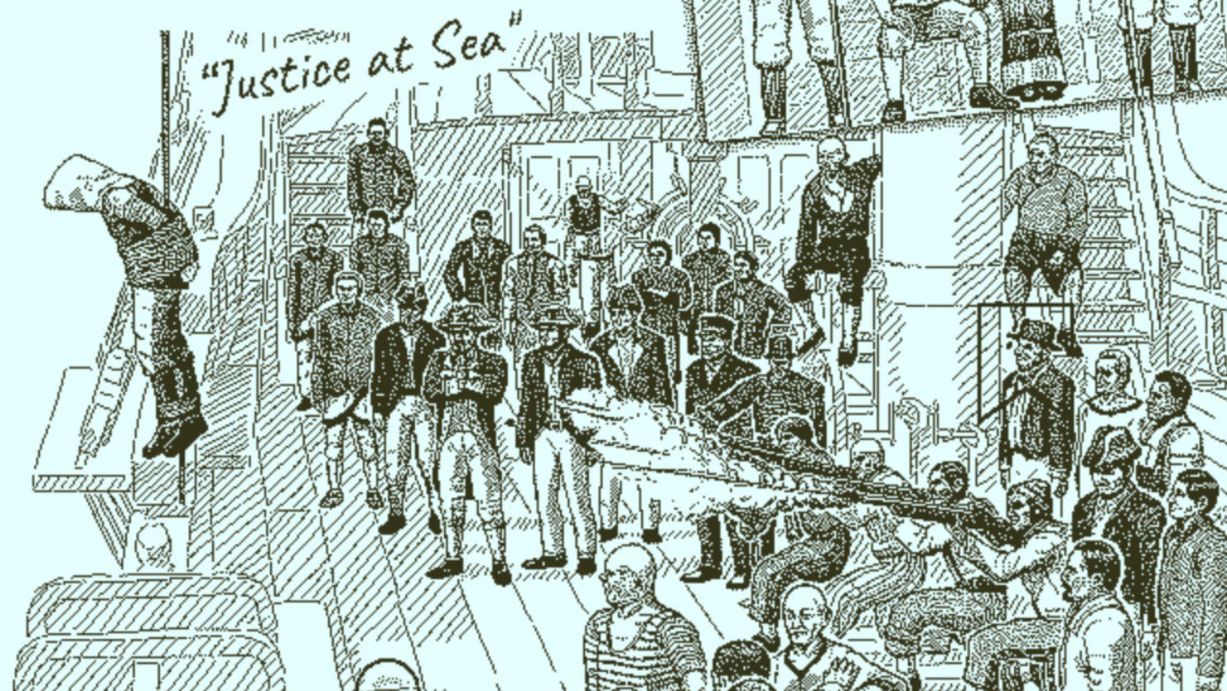

Every nautical story is anchored in two places at once; the big stage of the ocean, and the smaller one of the ship, circumscribed and contained within the former. The sheer contrast and imbalance between the two is full of dramatic potential. The Obra Dinn is a small world in its own right, a place where people sleep and work, play and socialise, live and die. With its crew and passengers from many countries and walks of life, it’s a small-scale mirror image of the larger world around it, but also far removed from it. The conduct and routines of its inhabitants and the use of its spaces are governed by rules which we as players have to figure out for ourselves. Mates are accompanied by stewards, officers have their own cabins while sailors must content themselves with hammocks, and the working environment of the carpenter in his workshop is very different from that of a topman climbing the rigging.

But since Obra Dinn does a very good job of reminding us that people are unpredictable and life is messy, life on board is rarely as orderly as the East India Company would have liked. And while the intrusion of the sea in the form of a giant kraken and other monstrosities aren’t entirely without blame, there are far more interesting conflicts here. The Obra Dinn circumnavigates the maelstrom of lazy drama and recognises that the most compelling tensions come from within rather than without.

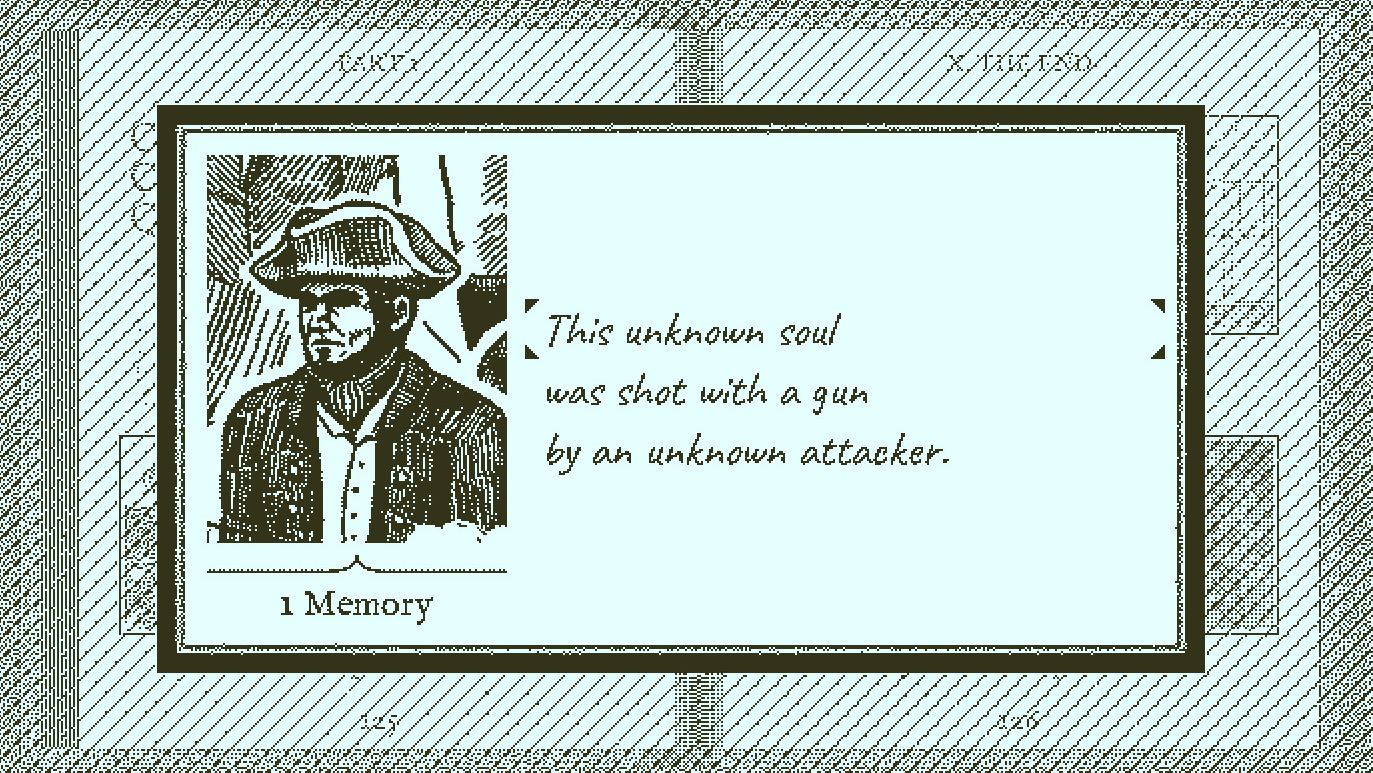

It is, after all, the obsession of the mad Ahab rather than the albino whale that famously dooms the Pequod. In Ian McGuire’s dark novel The North Water, it is the unlucky collision of a murderous sociopath and the greedy scheming of others which leads to shipwreck. Because of its out-of-order flashbacks, the fate of the Obra Dinn at first looks like a confused muddle of mutinies, storms, mad scrambles for survival and random sea monster attacks. However, it’s soon revealed that most of the blame should be placed on human greed and a botched theft by second mate Edward Nichols, which results in a murder, the execution of a Formosan scapegoat, and then spirals out into an escalating cacophony of mutinous plots, abductions, murders, revenge killings and an outright war between the Obra Dinn and the denizens of the deep.

This story can seem confused and haphazard at times. Its dizzying catalogue of unlikely calamities is almost a self-conscious reference book for the whole nautical disaster genre, listing all the ways one might perish at sea: Drowned, check. Stabbed, check. Eaten, smashed, strangled, check. And yet, its depiction of the noise and tensions aboard a vessel, with all its potential for conflict, misunderstandings and accidents, feels wonderfully lifelike and just as compelling as those of the best nautical stories told in other media. Wandering an abandoned vessel increasingly littered with corpses and phantoms conveys the density and claustrophobia of this place, packed with all kinds of people who often do not even speak the same language, and whose informal bonds are often in competition with the official hierarchy of a ship.

In this way, the job of the sea monsters isn’t to excite, not even to provide tangible symbols for the violence of the sea, but to intensify the latent disorder already present within the ship. The forces of the sea soften the seemingly rigid borders defined by planks and hull. They dissolve the illusion of strict social order that is supposed to hold together crew and passengers like a thick layer of tar. People leave their posts to help where help is needed most, steal provisions to abandon ship, or withdraw themselves to quiet corners to discuss mutinous plans. In the end, the few remaining crew members commit the ultimate sacrilege and try to murder their captain. Few things would be able to survive the savage pummelling of a kraken, and neither proper decorum nor a rather abstract sense of duty are among them.

The unfolding chaos and noise is not just compelling to witness, but also has an important role to play. The disorder of the monsters destabilises the scaffold-like rigging that supports us as we go about making connections and identifying crew members. The cunning investigator still has to rely on their knowledge or educated guesses about how things aboard this ship are supposed to work (who sleeps where, what clothes are worn by people of different rank, how some people like mates and their stewards tend to move together) but now you also have to take into account the irregularities that come from unpredictable human action and invasions of murderous mermaids. As a result, Obra Dinn's puzzles are less about pure logic than about understanding of the fuzziness of human behaviour and relationships.

In other words, Obra Dinn takes up the tropes of nautical disaster stories not to repeat or subvert them, but to repurpose them for the format of the mystery puzzle game. The pairing of cerebral puzzle solving and the spectacle of a tragedy at sea is not as strange a combination as it sounds. After all, stories of historical shipwrecks would often come to people like so much flotsam washed ashore; uncertain and fragmentary bits of information around which stories and mysteries might grow like a pearl from a grain of sand. In this way, Obra Dinn capitalises on one of the most intriguing aspects of the genre by asking us to piece together the puzzle ourselves. It blows fresh wind into the sails of both the nautical disaster story as well as the puzzle game, infusing the latter with the humanity the genre often lacks, while giving us the opportunity to experience the former from a new vantage point.