Premature Evaluation - Sigma Theory: Global Cold War

From the developers of Out There

There are few people I find as fascinating as Mister Julian Assange, the debonair hacker and out-of-work Geralt cosplayer who hid inside an embassy for seven years, skateboarding into the ambassador’s bedroom and demanding to know the new wi-fi password so often that they finally got annoyed and kicked him out.

Assange has the campy flare of a mid-tier Drag Race contestant, randomly appearing on his chic little balcony like he’s Evita addressing his adoring public, except instead of Madonna it’s Santa Claus from a Japanese horror film. One time, he popped out of his room waving a hundred-page United Nations ruling, like he was Michael Jackson and the document was an imperilled, dangling baby. He’d clearly used Ecuador’s inkjet to print it out too, tying up the only printer in the building for any diplomats who needed it for scanning in trade agreements and whatnot. He clutched that thick ream of purloined A4, still warm from the printer tray, like it belonged to him. And it was in full CMYK too, judging by the brilliant azure blue of the UN logo on the first page. There was a man who wasn’t paying for his own printer cartridges. And for that reason, at least, he deserves to be in prison forever.

So, in single-player, turn-based strategy game Sigma Theory, you are the head of intelligence for your chosen nation during a new cold war, ushered in by an era of rapid and sudden technological advancement. Countries across the globe have simultaneously discovered a brand new tech tree, which will unlock incredible new discoveries the likes of which have hitherto only existed in the most Deus Exish of our paperback science-fiction novellas. We’re talking transhumanism, robotic eyes that follow you around the room, singularities, bionics, hypnosis, space taxis, an algorithm that can predict the stock market – all of them are course-of-history bothering inventions, world-changing prizes to be unlocked by whichever nation can research them first.

Here’s where your secret army of assorted Julians Assange comes in. You’ve got a paltry two scientists to begin with, covering a mere two of the five branches of this new Sigma science tree, and a couple of drones to send out around the X-COM style world map. You can hire four undercover agents to head out into the field to locate and investigate the science teams and governments of your allies, with the ultimate goal of coercing their nerds to defect to your side one by one. This is all while whistling innocently to yourself, pretending that the world’s countries are all still bezzie mates, and trying to avoid eye contact with the prime minister of Turkey during continental breakfasts at G20 summits.

By the way, I’ve probably grossly oversold how cool Julian Assange comes across in this comparison. In Sigma Theory there are hacker agents that will defect to other nations and steal your research to use against you, certainly, but none that will sulk in their bedroom for the best part of a decade and then smear their own excrement over the walls in a dirty protest. At least none that I’ve seen so far. I’m still unlocking new agents.

Moving your people around the map is consistent with the futuristic cold war setting. You can’t just whizz over the Atlantic in a military gunship to airdrop them into a populated area, instead they either travel on regular airline routes (which means they’ve got to forfeit any weapons they’ve got) or they can take a more circuitous route over land and sea to keep hold of their armaments (the Megabus method). This way they also avoid any local arrest warrants they might have.

Once in place, your agents can start uncovering intel, locating scientists, and if they’re especially skillful, digging up dirt on the country’s leader, all at the risk of failing and increasing tensions between nations. At any time you can call a meeting with another head of state and use your dossier of intel against them, either by appealing to their traits or by showing them the compromising photographs you found in their Dropbox folder called “boring tax stuff nvm lol”. Your dialogue choices send an affinity meter swinging up and down, hopefully so that when you ask to borrow a scientist, it’s high enough that they’ll hand one over without asking for anything in return.

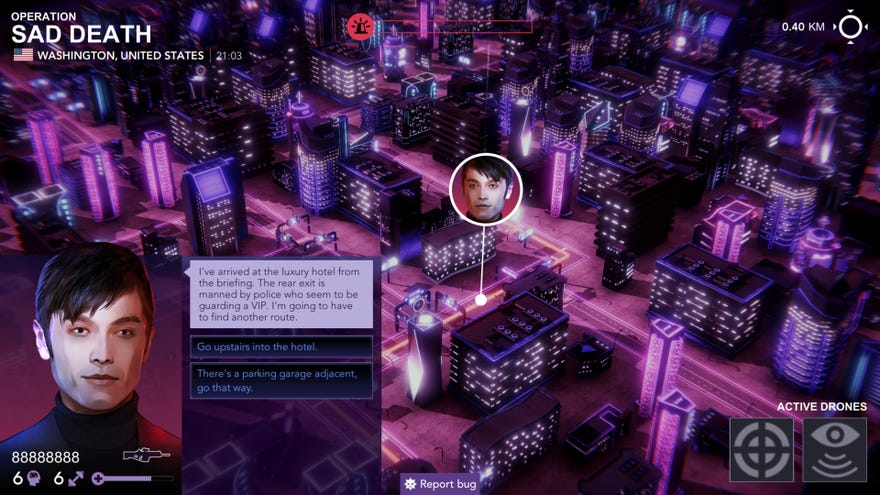

As it plays out, Sigma Theory’s dual strategy prongs are chummy diplomacy and filthy espionage, and this is no more felt than when exfiltrating a defecting (or sometimes straight up abducted) scientist. An escape dash mini-game has your agent sneaking through the city to an extraction point, encountering potentially dangerous situations along the way and prompting you to choose the appropriate course of action. An understanding of your agent’s personality helps in choosing the best route – whether or not they should beat a couple of policemen to death, or jump into a taxi to slip past a checkpoint – as does having surveillance drones in place and a sufficiently low threat level with the host nation. Failure means capture, which opens up the opportunity to send in another agent to spring them out of prison.

There’s a well written meta-game playing out as you research these paradigm-obliterating technologies too, which tackles some meaty themes of technophobia and the encroaching paranoia of the world’s superpowers. The fear that another, less scrupulous nation might use this new technology for nefarious means justifies your own nation doing precisely that before anybody else can. Though it doesn’t have to happen this way, you can freely share your discoveries with the rest of the world as you make them, keep them secret, or even sell them off to shady private enterprises, whose allegiances have an effect on your game. I sold advanced hypnosis tech to a military contractor and turned every country in the world into a dictatorial police state overnight, after I naively believed I’d only be helping a bunch of people get over their fear of flying. A doomsday clock keeps track of these kinds of things, and creeps closer to midnight the more reckless you are. Your scientists have scruples too, annoyingly, and are just as prone to being turned as anybody else.

These complex ethical arguments can be a little more domestic too. Like when my sexy husband, the handsome and brilliant Andreas Bourdain (he took my surname, which I thought was a nice touch), asked me if I wouldn’t mind /not/ giving the world limitless free energy, because he still owns a bunch of nuclear power plants in the third world. I gave him two months to divest his nuclear interests, a cowardly hedged bet that inched the world one minute closer to annihilation, and our marriage one step closer to divorce.

Andreas, I love you honey, but the world needs bitcoins.