Premature Evaluation: The Endless Mission

Dee aye why

Few things fill me with dread more than a blank canvas, especially one that’s aching with untold potential, or even worse, infinite possibility. I'm talking about Little Big Planet, Super Mario Maker, and now this, The Endless Mission; games in which you are thrust into the role of the world’s omnipotent architect, an unpaid and underqualified level designer shackled with the burdensome responsibility of creation. It takes a real level designer many decades and hundreds of thousands of pounds to learn their craft, probably. That this genre expects me – a man regularly pushed to the cusp of a mental break when building IKEA furniture – to design anything worth actually playing, is frankly insulting to everybody involved.

All of these games start out in precisely the same way. You wake up in some ivory white mausoleum in the clouds, where in the corner sits a fatherly old man with rosy cheeks and a big bushy moustache, and he’s definitely God, and he turns to you with a twinkle in his eyes and chuckles, “this is your world now, my beautiful child. Anything you can imagine can be made real. There are no limitations but those that you set yourself. And all you have to do...” he pauses dramatically, placing a coarse finger on your lips as the walls of the imaginarium collapse into themselves like a toppling house of cards, folding through higher dimensions and blinking out of existence as the sound of a tuning fork hitting crystal rings clear in the cold air. “Is think it.”

And then God is gone in a puff of logic, and he’s taken the clouds and all of the details with him, and you’re left standing on a vast and featureless grid beneath a sunless grey-brown sky. Press F to sculpt your first imagination cube, says an on-screen prompt. So you do, and with a wet pop a single joyless object materialises there in the airless voidscape. Dooming an unconsenting cube to exist here alongside you forever is a small act of selfishness, and you soon learn that sharing the curse of perpetual loneliness somehow does not make the burden half as heavy. You can now pick which colour the cube is. Green? Nice. Well done, you’re on your way to crafting your first level.

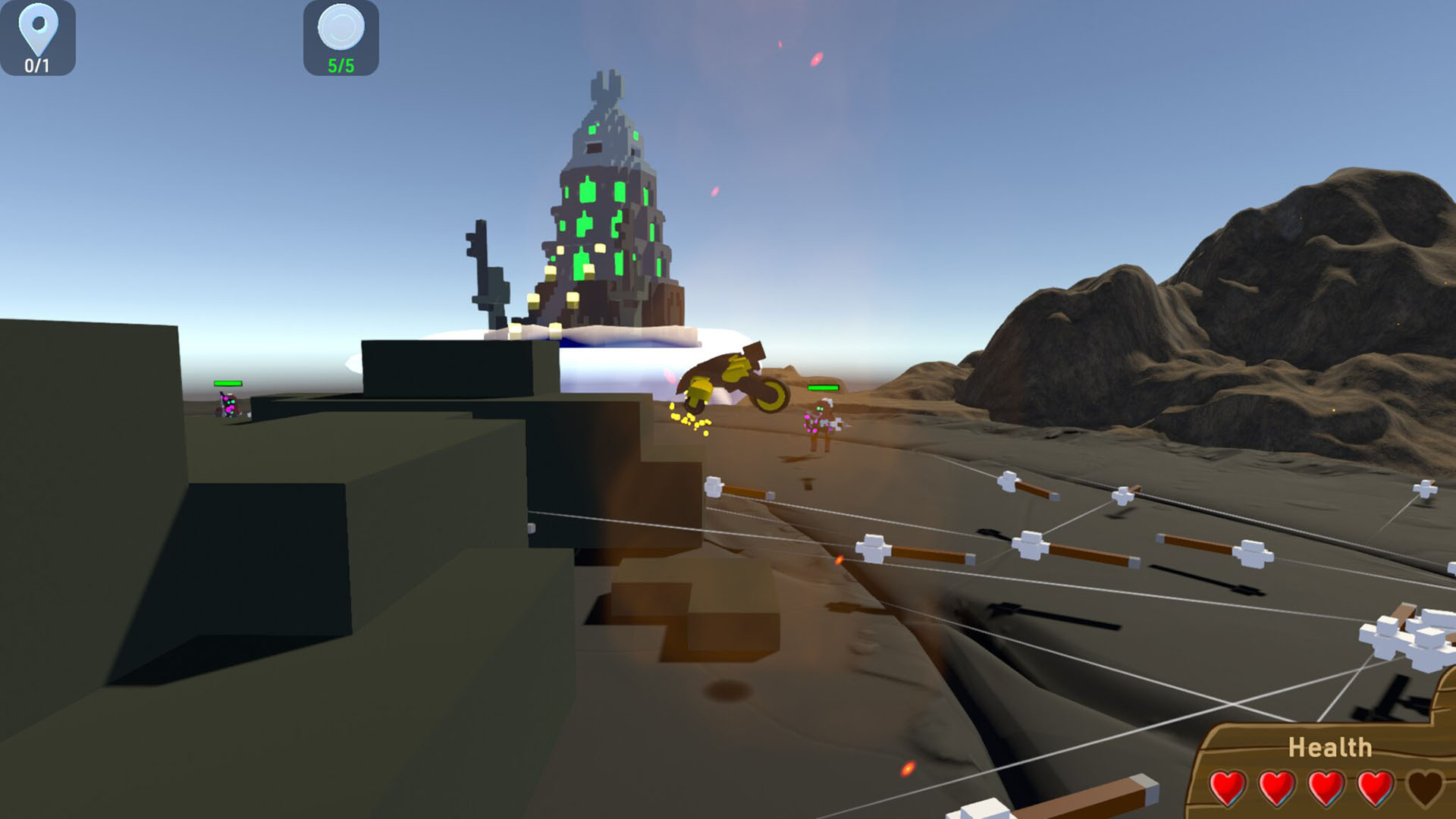

The Endless Mission at least spares you from the incapacitating horror of a totally empty sheet of paper, instead giving you three existing genres to start out with. There’s a floaty platformer, in which you play a pirate cat on a mission to collect some pineapples. There’s a Flash-tier real-time strategy game, in which you play a hovering mouse cursor commanding little voxelated armies. And there’s a futuristic racer, which looks to have been thrown together really quickly as some background detail for an arcade scene in a 90s action film, after the legal team couldn’t secure the rights to the PS1 version of WipeOut. Everything has the production value of something you’d find free on a CD-ROM inside a box of Shreddies.

Play any of the game’s pre-built levels and you have the ability to switch into a live editing mode, clicking on rocks and platforms and enemies to edit their attributes on the fly. You can make things really big, or really small, or rotate them on the spot, or position them so that they’re hovering uselessly in the air. You can adjust the dimensions of the main character, scaling them up on one axis so that they’re twenty feet tall and paper thin, or tinkering with gravity so that they zoom off helplessly into the sky.

This is all to familiarise the player with the editing tools available to them, and the game’s incongruously well-voiced story mode – in which the universe’s benevolent guide has you popping into each genre in turn to fix some problems with corrupt data – gradually unlocks more ways to hack the world. Far from an enjoyable puzzle concept, these real-time hacks feel more like you’re fixing the game as you play it.

Slip into the full editor and you’ll run forehead-first into a sheer wall of insurmountable complexity, the severity of which no amount of hand-holding tutorials could ever hope to bring you up to speed with. There’s an unbridgeable chasm between playfully tweaking a soldier’s attack strength so that he can successfully overpower a bad guy in the story mode, and constructing anything that could reasonably be considered a useful creative expression in the editor.

The most successful example of this genre, Media Molecule’s Little Big Planet, was a masterclass in surgical learning curves and intuitive tools and interfaces, turning new players into reasonably competent level designers over the course of a curated series of platform levels designed to drip feed and invisibly test an understanding of the building blocks of the game world.

If Little Big Planet was a thoughtful, caring tutor, then The Endless Mission is more likely to give new players a concussion and dump them by the side of the road. The game is at least very ambitious in the amount of control it wants to eventually hand to its players, but there is just no crossover of people who want this degree of creative jurisdiction over the thing they’re playing, and those who are unwilling to sit in front of a Unity editor to make it themselves from scratch. On a practical level, the game struggles to run on my machine, which is perfectly capable of playing the new cowboy game with all the settings turned up. Editing anything with these flipbook framerates becomes a test of your patience.

This isn’t simply a failure of my own ability or imagination either. At any time you can pull up a list of other players’ creations (there are just a few dozen) and they are all – apologies if you’ve made one – tremendously bad. Just damningly, depressingly awful. The limited genres are clumsily remixed into a series of abortive arcade games, reused assets bolted together like some horrible Frankenstein creation, each one more confounding and surreal than the last. In one, you’re the pirate cat leaping through platforms hanging in an empty white space. In another, you’re the car driving along a fire escape, collecting coins on an endless and inescapably pointless mission.

I left bamboozled and afraid, but more certain than ever that the means of production must never fall into the hands of the proletariat.