Three hours in Total War: Three Kingdoms, the first Total War soap opera

Bulls in a China shop

Once about people in the aggregate, Total War is increasingly a series about the antics of individuals. There's something of the slippage from RTS to MOBA in how Creative Assembly has edged towards a more intimate breed of strategy, built around asymmetrical relationships between overdressed oddballs rather than mere economic considerations or the splash of army on army. Total Warhammer is the obvious play-maker there, with its vast archive of Games Workshop celebrities, but in Total War: Three Kingdoms, we may have reached a new tipping point. Where even Twarhammer's crusty old lords and heroes are more structuring devices or combat specialists than characters, Creative Assembly's latest often feels like the stabbier kind of daytime TV.

Based on three hours with a campaign build, characters act on you much more often than ever before, and to grander effect -- from rivals trying to drag you into their orbit, to the larger-than-life souls who (providing you don't annoy them) lead your armies and run your provinces. For instance: during my first hour I managed to become ruler of a bunch of cities by doing almost nothing. I'd been nice to a neighbouring ruler a few turns before by, as far as I can recall, agreeing not to stamp all over his units till it suited me. Said ruler then took to his deathbed and, overcome by memories of my wisdom and comportment, named me as his heir.

Admittedly, this kind of thing happens to my man Liu Bei -- one of the game's 11 faction leaders -- quite a lot. A rugged “Virtuous Idealist” and friend to the commoner, he tends to be viewed more favourably by other parties in the early game. As grandson of a previous Emperor, he can also peaceably annex cities under the control of the old Han Dynasty by spending “unity”, a specialised resource earned by doing nice things for other characters. Still, it was a bit of a shock to find five more settlements in my hand, especially given that I'd just run out of food for my existing towns. Also a surprise: my dearly departed neighbour's lands were choc-a-bloc with raiding armies.

The AI turn hadn't even ended before another leader, the “Hubristic Warlord” Yuan Shao, popped up to ask me to join his coalition, presumably drawn to my spiking fortunes. Then a bunch of other, lesser bigwigs asked me if I could ask Yuan Shao if they could join the coalition too (this entails haggling with other members of the coalition on the diplomacy screen). Then some sneaky devil called Yuan Shu tried to bribe me into endorsing his claim to the old imperial throne. The outcome of all this hustle was that my view of the world map expanded overnight from a sleepy circle of mountains to around one fifth of a viciously contested continent, while my food reserves sank even further into the red. I didn't even have time to put down my tea.

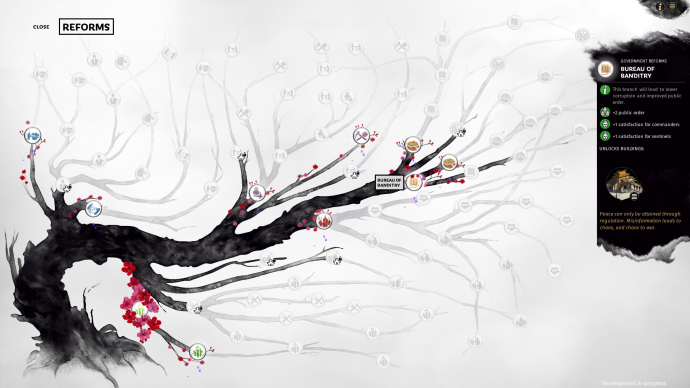

Since reading Brendan's E3 preview and trying out a battlefield demo myself in August I've been wondering how far Total War's social dynamics go, in a game that is still broadly about tech trees, taking cities, building up cash reserves and blindsiding the bejeezus out of dug-in archers. There are still plenty of things I haven't explored -- in particular, spying, whereby you can pretend to fire a hero in the hope that a rival will recruit them and, better yet, hand them a massive retinue and the keys to a city. But thus far, it feels like Creative Assembly's tacit channelling of Game of Thrones and Crusader Kings II is yielding fruit. There's so much more to consider as a faction leader, both in terms of managing other leaders and keeping a lid on the antics of tempestuous followers.

For instance, you can assign your buddies to a variety of positions within your empire, from faction heir right on down to lowly town administrator. Give the right people the right jobs and you'll reap a tidy assortment of buffs -- when made heir to your faction, mountain king Zhang Yan bequeaths empire-wide bonuses to troop movement through forests, for example, while other characters boost city stats like public order. Beyond that, you need to make appointments because anybody who doesn't feel like they're doing their bit will receive an on-going morale cut, to the point that they'll up and quit.

Each supporting character's allegiance will also rise or fall depending on how well they think you're running the show -- who you keep at arm's length, who you keep faith with, who you betray. And then there's the question of relationships between individual characters, all evolving as formations clash and territory changes hands: rivalries, blood bonds, tantrums when you pick this hero over that one for promotion, long-standing friendships based on shared accomplishments, or the squabbling that results when you put heroes with fragile egos in the same army.

OK, so I'm still getting a sense of the practical payoffs beyond people in loud hats calling each other arseholes on the battlefield, but even early on, there's a lot of background churn. At one point I enlisted a second hero to back up one of my generals (heroes have classes and other traits that determine what kind of troops they can recruit, so you'll probably want a mix of personalities in any decent-sized army). A turn later the two were best of friends, gaining bonuses when they fought side by side.

Much of this toing-and-froing reflects the choice of period -- right after the collapse of the Han Dynasty, with the old emperor a hostage of the renegade tyrant Dong Zhou. “Everyone's sort of retreating to their homes to consider their ambitions,” observes narrative designer Peter Stewart. “There's a lot of powerplay in politics in the opening 10 turns or so, when everybody's trying to solidify who's worth trusting and who isn't.” If things do calm down past a point, once each side has a few settlements to tend to, there will still be plenty of jockeying for position leftover for the endgame.

The aim of every faction leader is to become emperor, which involves not just amassing material power but climbing a faction hierarchy. Rise high enough to declare yourself emperor, and the second and third strongest leaders will launch competing claims, rallying their allies and vassals to form the three kingdoms of the title. The exact composition of those power blocs will, Stewart says, reflect the many spats, agreements and conspiracies that have unfolded along the way. “Your rivals and nemeses start to make themselves known, and you'll see who your true friends are and who you probably shouldn't have trusted all along.”

The fact that your lords and lordlings bear telltale epithets such as “Arrogant Opportunist” seems to cut against this promise of continent-wide intrigue, but Stewart assures me that characters can still surprise, even if you know broadly what to expect. Indeed, knowing how they

The longterm effects of such gambles aside, one aspect of Three Kingdoms I'm still working out is Wu Xing. It's a concept from ancient Chinese philosophy, referring to the relations between the elements of wood, water, fire, metal and earth. Each building and hero in the game belongs to one of these elements and either defeats or supports another. “So you have this idea of the Strategist class with his units being very strong against fire, because water douses fire,” comments senior designer Leif Walter. “At the same time the Strategist supports wood, because water nourishes wood, so the Strategist unlocks formations for spearmen of the wood element.”

As a “design lens”, Wu Xing cuts against the triangular logic that defines older Total Wars, though you'll still feel the old strengths and weaknesses in play during combat. “We're sort of moving away from the idea of rock-paper-scissors, which is one beats one beats one beats one,” says Stewart. “This is supports-defeats, supports-defeats. And when you connect them all up, it's quite a complicated little map, and that underpins a lot of the gameplay design, which is also relevant to the history, because it underpins a lot of how they thought about life at the time.” It's a change of direction that could prove quietly transformative, and as with those barmy character mechanics, I look forward to digging into the fine details.