Unearthing the folk horror of Mundaun

Scary as folk

The rural idyll has a strange pull on us. Picture a green and pleasant land: white sheep dot rolling hills like puffs from a steam train. Children with flowers in their hair dance round coloured maypoles. All the while, in a white marquee, where bunting flaps in the breeze, oversized ribbons are being awarded for best sponge cake. Dig deeper however and we discover old hatreds buried beneath the pastures and furrowed ground.

There is growing nostalgia for the quaint charm of pastoral life, but alongside this a subgenre of horror that has seen a revival matched only by the restless undead. This is folk horror, with its haunting landscapes and eerie atmosphere. It’s a somewhat shapeless category that evaporates as soon as you try to pin it down. But one game is trying to capture it.

Most commonly, folk horror refers to a string of British films from 1968-1974 known as the Unholy Trinity: Witchfinder General, The Blood on Satan’s Claw and The Wicker Man (to be clear, I mean the original, not the Nicolas Cage remake which is horrifying in its own unique way). Set in picturesque places steeped in folklore, these films offer muffled glimpses of horror as opposed to full-frontal shocks. They’re weird tales of black magic, superstitious cults, strange rituals and satanic pacts that burrow into the hate-filled heart of the nation.

Despite folk horror coming to define a particular era of British film and TV, the genre can just as easily apply to work from other times and places. There are contemporary film examples like A Field In England and The Witch. On top of this, it's distinguishable in literature, in the short stories of writers like M.R. James and Arthur Machen, both of whom H.P. Lovecraft called “modern masters”. Folk horror is international, and people are increasingly interested in it today. As the genre spans multiple forms of media, it raises the question: why are there so few video game examples? Where’s our Wicker Man?

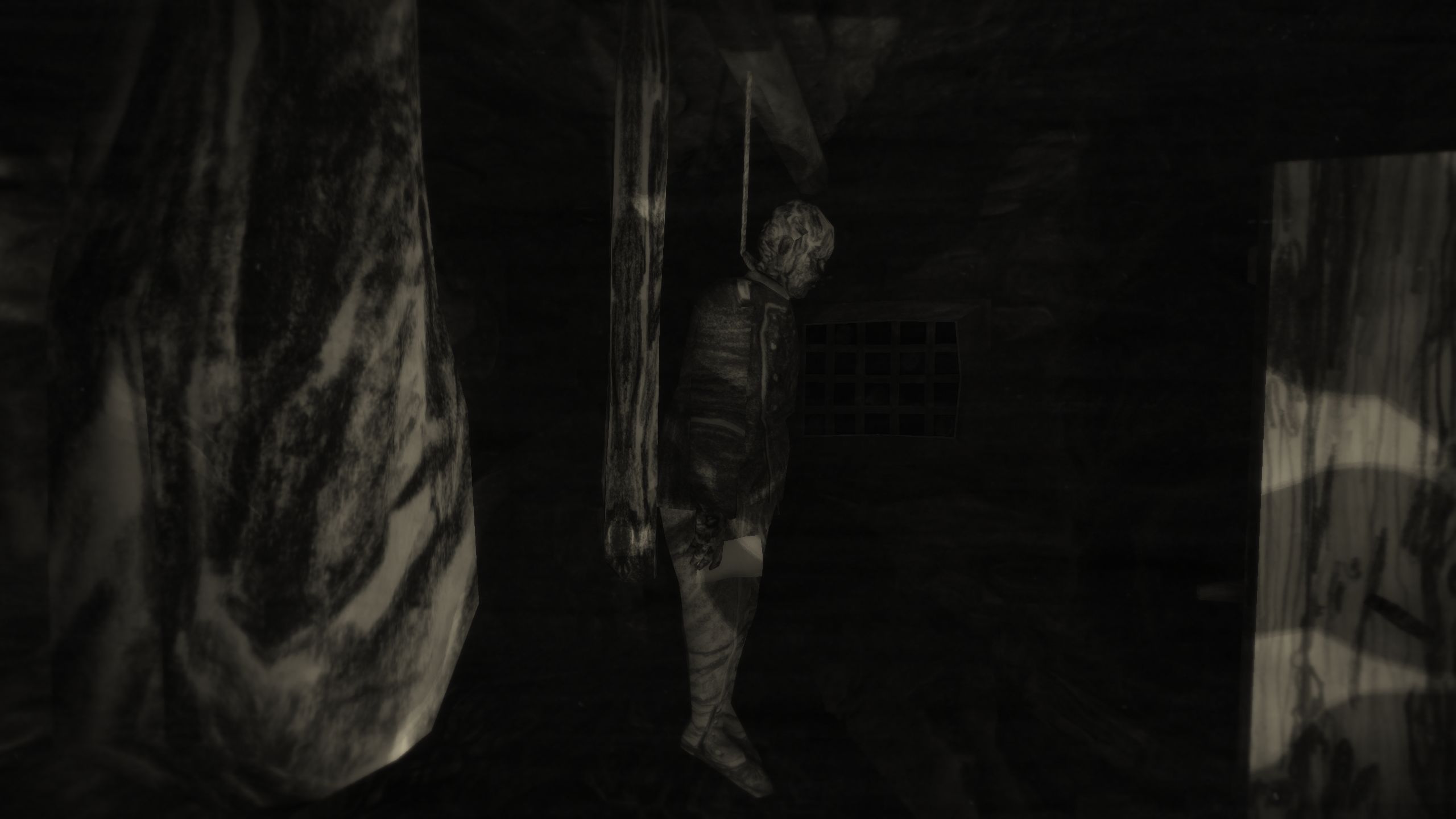

It might be Mundaun. This upcoming "hand-pencilled first-person horror tale" from Swiss game designer and illustrator Michel Ziegler has more than a few similarities to the 1973 British cult classic in which Christopher Lee and his pagan cult burn people alive inside a giant wicker effigy. In Mundaun you'll explore an open, alpine area, all the while looking for traces of some diabolical secret by chatting to kooky locals and solving puzzles in the mountain air. As with The Wicker Man’s Sergeant Howie, you arrive in a peculiar place and have to find out what in God’s name is going on. There are also creatures which roam the land -- such as the haymen, who cut a familiar straw-form. Most recognisably, it evokes a very specific mood. Michel explains it as there being "just something in the air, something unsettling.”

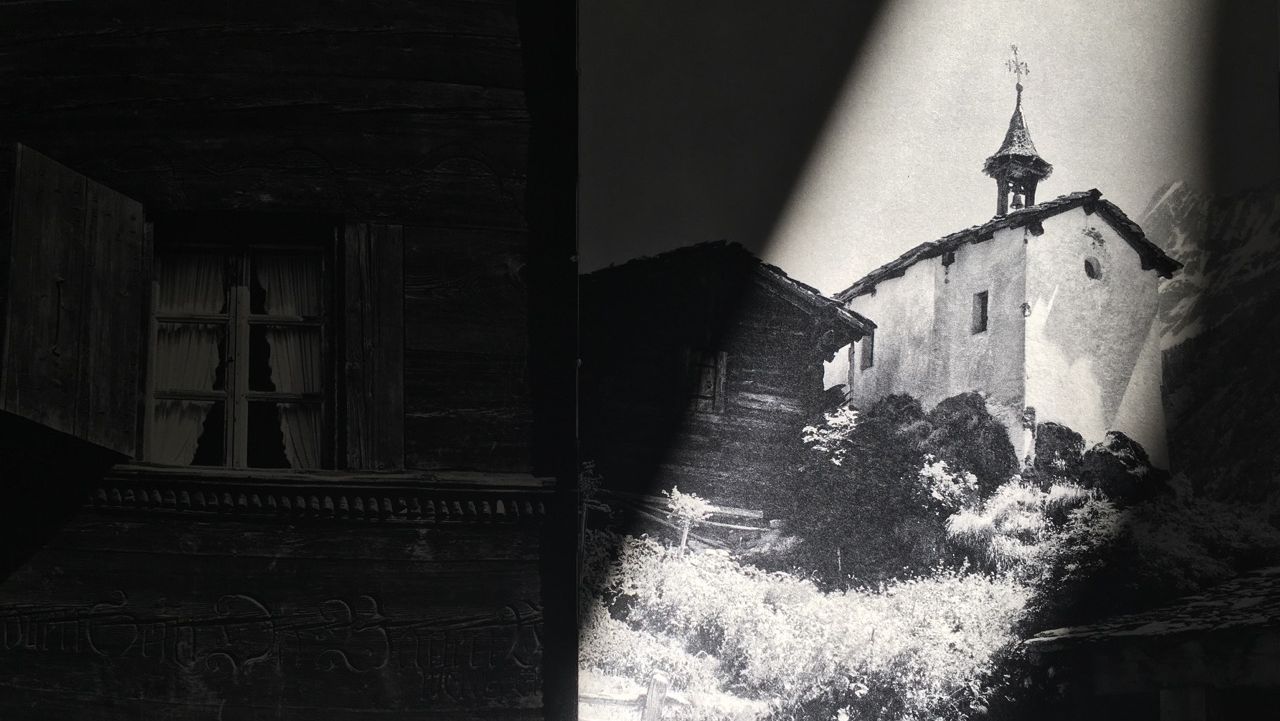

The landscape of Mundaun, based on a real area of the Swiss alps, couldn’t be further from The Wicker Man’s Summerisle. This setting was the starting point for Michel.

“I’ve always been fascinated by this particular landscape,” he says, “the steepness and the old buildings. It is a place almost standing still in time, where the past is visibly reaching into the present.”

Like so much folk horror, the land plays more than a background role -- it becomes a character in itself, a historical presence that reaches out and affects us, as if it possessed agency.

In Michel’s desire to evoke the “eerie, mysterious quality” of the past, Mundaun’s landscapes chip away at the deathly quiet so often associated with rustic, provincial life. In his essay on the eeriness of the countryside, Robert Macfarlane talks about fictions which reveal the “skull beneath the skin”. This is perhaps the most important aspect of folk horror -- that comforting, Arcadian lands hide dark secrets and ancient atrocities. Similarly, Mundaun’s own mysteries will creep to the surface, the land peeling back to reveal horrors over the course of the game. Evil lingers, waiting to be unearthed, or to break out.

Click GIF to watch.

Many of Michel’s inspirations involve a degree of shadowed ambiguity. All of Mundaun’s textures are pencilled by hand, a style which seems to turn even everyday objects into what Michel calls “dark, oppressive things”. Another influence is the art of Pieter Bruegel, who painted landscapes but also peasantry. Regular farming folk.

“There is an ominous undercurrent in Bruegel’s drawings of the hooded apiarists,” says Michel. “Are they really just going about their work?”

Bruegel’s faceless beekeepers (“Not the Bees!”), who could just as well be masked cultists, are the basis of one of several enemy types in the game, and reinforce a certain suspicion towards folk and their opaque ways. This is common to the genre, with folk being inscrutable or difficult to decipher. According to Michel, Mundaun’s villager’s possess “their own obscure spoken language,” highlighting the ability of communities to alienate. You do not belong.

The depiction of rural labour is important to folk horror. The director of The Blood on Satan’s Claw, Piers Haggard, has talked about creating a “sense of the soil” under which rotten things might fester and threaten to emerge. Michel wants to evoke this uncertainty.

“The way that our ancestors worked the land seems almost forgotten to us,” he says “It’s just not a modern concern in our daily lives. Some of their tools and contraptions seem archaic and it fuels the darker part of my imagination to consider what they might have been for.”

Michel has a clear interest in the grounded life of his world’s inhabitants.

“Incorporating details is very important, as is visual research. I never want to default to the generic.”

Like in other examples of the genre, such as the malignant whistle in M.R. James’ Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad, artifacts have a powerful presence. In James’ story, a professor uncovers an old whistle amongst Templar ruins. Of course, like anyone would, he gives it a good blow, only to be tormented by infernal visions and assaulted by crumpled linen. Many of James’ short stories feature these kinds of objects which awaken the supernatural, giving the impression that mundane things can contain unknowable horrors.

As with The Wicker Man, Mundaun begins with the arrival of an outsider, that ubiquitous folk horror archetype, alienated amidst the strange customs and traditions of an isolated village. For Michel this arrival “just makes sense.”

“The audience can discover this new, strange world through their own eyes.”

It’s also an opportunity to “set the mood”. The bus journey to Mundaun was heavily inspired by the title sequence and remote hotel of The Shining, he says.

Many of the elements that come across as strange and ancient and which act to alienate the player do so due to their superstitious and religious nature. “Symbols of Christianity are omnipresent in Mundaun,” says Michel. This is evident in places like the meticulously detailed chapel which is based on a real location.

“There are many signs of superstition in the form of carvings or trinkets, supposedly protecting against evil spirits. We have many myths in which the devil walks among us, scheming and tricking mortals into pacts. The fear of and attempt to defend against and banish this old evil is the main factor in the presence of religious imagery.”

“Probably the single biggest influence on Mundaun is The Black Spider,” reveals Michel.

The Black Spider is a novella written by Swiss author Jeremias Gotthelf. It uses the narrative frame of an ancient black post -- an artifact like M.R. James’ haunted whistle -- to explore the history of the village, where in days past desperate peasants made a deal with the devil, only to renege on the contract and be blighted by plague and terrorised by a demonic spider. The black post marks the point where a brave mother defeated the creature, but it also symbolises the possibility of a resurfacing; of the repressed returning. Michel says he uses a similar narrative structure in Mundaun to explore the past, although he points out that Mundaun shares only “the mood, tone and certain motifs of folk tales, not their plot.”

“The past and its buried secrets are a big theme throughout Mundaun. On his journey up the mountain, the player will uncover what happened piece by piece through dreamlike flashbacks.”

One scene that Michel has shown depicts soldiers buried in the snow rising up out of the earth. Another tale shared on his developer blog tells of an old corporal who hides-out in a bunker years after the war has ended. Perhaps this is what Michel calls the “past resurfacing”.

Another influence on Michel’s work are old photographs and postcards depicting rural life. Historic photographs are almost inherently eerie and ghost-like, and Michel uses them as a concrete reference to build his “artifacts, buildings, clothes and faces.” These mementos of alpine life are “hugely influential”.

“The contrast in those photos leads to really dark shadows,” he says. “They are beautiful and haunting, and who knows what is hiding in those pitch black corners.”

I asked Michel whether he thought there was any contemporary relevance to the kind of horror he was creating.

“Maybe we fantasise about living in a past where things were simpler, more clear and contained. An honest life, closer to nature. But then of course, horrible things occurred in this supposedly quaint world.”

Our enchanted visions of the tranquil countryside have always been mythical. Forgotten histories -- dispossession, poverty, war, massacre and murder -- threaten to burst from the spectral soil like so many sores and blisters. If anything explains the recent revival of folk horror, it is the idea that the past is not so easily exorcised. Old hatreds never remain buried.

Mundaun is due out in Spring 2019 September 2019