The RPG Scrollbars: Voices In Your Ear

List-listen to this, hacker...

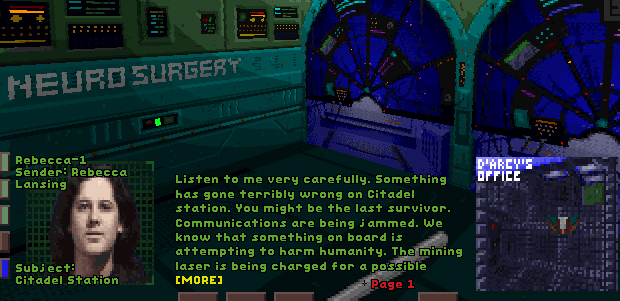

Looking back on System Shock, one part inevitably stands out more than any other. SHODAN. The goddess of Citadel Station. With her words she turned a futuristic maze into a horrific hunter/hunted situation, where survival was about clawing back control and beating the machine at her own game. It’s an impressive achievement… but especially when you consider that really, she was little more than a few well written voice files and a world that let them temporarily seem like something more.

Since the start of gaming though, there’s been technology… and there’s been showmanship. One often gets mistaken for the other. We see advanced AI in characters that simply broadcast what they’re doing. A simple line of dialogue at the right moment can make a game. In Deus Ex for instance, being shouted at for going into the ladies’ wasn’t simply a cute bit of scripting, but its way of saying that it was always watching. And you were never going to know what it was watching out for.

Sometimes, characters just commenting at all can create wonders.

It’s hard to remember just how big of a deal speech was in the 80s and early 90s, back when most of us had a PC speaker capable of half-heartedly farting out a tune. A few companies, notably Access, managed to squeeze more out of it, including speech. Arcade machines too occasionally served up the odd soundbyte, at a reported price of around $1,000 a word. But computers didn’t talk much until the 90s. First they didn’t have the ability. Later, they lacked the storage space. While there were talkie games and CD-ROMs and SoundBlasters before it, it wasn’t really until ’95 or so that most PC gamers could be expected to have both. For ages, speech was largely a novelty.

Origin of course was well ahead of that curve, as befits the company whose motto was “Your PC Can’t Run This”. Their games shipped on floppy, but it was possible to buy “Speech Packs” to jazz them up a little. And I do mean a little. Wing Commander II for instance was largely restricted to in-cockpit comments. Ultima VIII: Pagan only gave voice to a handful of characters, like the Titans, and the kind of voice that answered the question ‘what does buyer’s remorse sound like?’

But Ultima VII… that was a different story. If you had a SoundBlaster, the quest took on a whole different atmosphere thanks to the villain, the Guardian, being able to break into your game at a whim. He could do it without sound, his big head being superimposed onto the screen with a caption, but that wasn’t half as effective as his gentle sentiment to “Sleep, Avatar…” when you went to bed, or finger-wagging “Thou shouldst not do that, Avatar!” when you inevitably pinched something. The use of speech turned him from a villain who honestly didn’t really do anything much into a focus for the entire quest. He wasn’t in some spooky castle. He was in your mind, slowly stripping away the pretence of having Britannia’s best interests at heart. Every time he spoke, his booming voice – the only voice in the game – was a mini jump-scare. Loud cacklings. False guidance. That smug sense of power; of being able to let you go about your business because failure isn't even on the table.

The result was one of RPGdom’s most memorable, most intimidating, most active feeling villains, despite, as said, him not even having a presence in the world until the final five seconds of the game. And also of course, looking a bit like a poorly constructed Muppet. (Even Origin admitted it, via Easter Egg...)

Fast forward only a couple of years. While I don’t know specifically if the Guardian was an influence on SHODAN, the fact that Warren Spector was on both series seems to make it likely. Certainly she uses much the same tricks – psychological ones as much as anything else. She doesn’t just threaten, because threats get old. She cajoles. She teases. She taunts. Above all else, she takes credit for everything that happens. The framework of Citadel Station, helped by already feeling like a coherent place where everything has a purpose, becomes her plaything.

Logically, you know that when you step into a room, all the walls fall down, and SHODAN declares “Welcome to my death machine,” that’s a trap by a human designer. In the moment though, it’s easy to imagine her having worked on this while you explored the previous level. It helps that, while it’s actually quite rare, System Shock is good at knowing when it’s time to show some degree of control, usually by having her think like a player. What would you do if you knew your enemy was going to arrive by lift? Send all of your people to mug them as they step onto the floor, of course. And so that’s what she does. Or if the player starts doing some real damage, bring in the heavy guns from another floor – the cyborg warriors and assassins who raise the stakes just as the player is feeling comfortable about slaying random zombie monsters.

The script of System Shock versus Shock: System Shock 2 (its full name according to the intro, making it official!) makes for interesting reading. For starters, it wasn’t really until then that SHODAN became fully developed as a character. In the original game for instance, she’s canonically male. Admittedly, for most players, that didn’t last too long. The gap between System Shock and the Enhanced CD version was only a couple of months, and it’s the CD version that’s been played the most. Most of her feminine traits however aren’t on display. By Shock 2 for instance, her model would have gone from a largely amorphous blob to a sharp-edged smirker with full lip and long wire hair, and her role as an evil mother figure/creation goddess more fully established – to the Many, as well as the player, who becomes an adopted agent to be groomed and enhanced.

What both games do well though is to balance out her mad howling with a sense of odd vulnerability – used for very different purposes in each game. In Shock 1 for instance you start the game with her having no idea who you are. She’s simply curious, but not too worried. “When my cyborgs bring you to the electrified interrogation bench, I will have your secret and you will learn more about pain than you ever wanted to know.” As you play and begin to dismantle her empire from within however, the taunts and threats take on an increasingly desperate edge. Every defeat is a chip away at her self-belief that she’s a goddess, and the entire game is spent chip-chipping away at exactly that. One security camera at a time. One plan at a time. Ultimately, getting the upper hand and winning. The regular check-ins move from being intimidation, to confirmation that everything’s gone well. Her palpable, if unspoken, frustration becomes the best reward you can possibly get. You want to beat her to annoy her.

Something else that both SHODAN and the Guardian have in common though goes beyond their actual script. Their ability to talk is in itself a demonstration of their power. Nobody else in Ultima had ever had a voice, if we ignore the truly appalling FM Towns version of Ultima VI that pretty much nobody has ever played anyway. In System Shock, you can collect audio logs from the dead, but the only other characters able to directly phone you up are all routinely cut off and silenced as soon as SHODAN notices. “I prefer a quiet station, thank you,” she almost yawns, with every repeated conversation being conveyed as being hard work on the part of would-be helpers.

This is largely why System Shock and Ultima VII managed to live on as the defining examples of the style. The more characters capable of talking to you, the less pronounced the effect becomes and the more voice becomes, well, just what we expect characters to have. Someone butting in during, say, a Dragon Age game is just another character, or someone merely casting some kind of magic spell. Instead, voices in heads largely went the other direction, towards friendly Mission Control Voice type figures. Blackbird in Strife for instance. Red from Penumbra. All well and good, but not the same as a good old nemesis to build up a proper antagonistic relationship with. Even when the villains joined the party, as in Deus Ex or Bioshock, it took a real hook like the latter's twist to get back into the spirit that their predecessors set up.

It’s really only now that we’ve seen characters able to top these early voices – GLaDOS for instance being funny rather than cacklingly megalomaniacal, or the Narrator in The Stanley Parable. Both offer definite debts to SHODAN especially, though dial down the mad ranting for comedy – ironically, resulting in the more horror-focused bits of both games being that much scarier as a result. Hurrah for contrast!

They do however prove that there’s life in the techniques that these games used so effectively way back in the day, which is all the more important with Shock 3 finally on the way. The awesome thing about now as opposed to then is that we finally have engines and designs capable of not just covering up the lack of real complexity, but pushing both sides to create worlds that feel responsive, and villains who seem to be doing the responding. While the Guardian’s era is over, SHODAN’s could be just beginning – with real schemes, world control, and far more than just empty threats.