Word Play

[A version of this feature was originally printed in UK videogames bible Edge. It's about the use of Text in videogames, both in the mainstream and over in the world of Interactive fiction. It features material from Chris Avellone (Planescape Torment), Sheldon Pacotti (Deus Ex), Adam Cadre (Photopia, Shrapnel) and Emily Short (Galatea, Floatpoint). I've expanded it to fit in in some of the quotes I couldn't fit in Edge's word-count. Which were many. If you've read my Planescape Retrospective, you'll recognise some key riffs. This feature very much grew from that one. And enough waffle. Let's do this thing.]

In the beginning was the word. And the word begat a phrase. And the phrase was “Avoid Missing Ball For High Score”. Gaming’s public relationship with words started here, and continues to this day. It’s these first furtive fumblings which produced the most lasting signifiers which define games in the public eye, and will continue to do so as long as the form continues to exist in its current state. Icons like “Extra Life” and “High Score” are as much a signifier of gaming as any of the corporate mascots.

But this isn't about that.

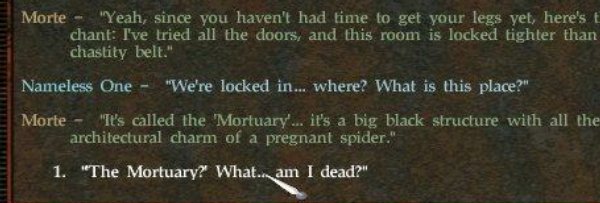

This is about their continuing use today. Words remain one of the more enigmatic yet efficient tools available to a professional game designer, and certainly one of the most overlooked. And its efficiency cannot really be overestimated – both in terms of player and development time. “Language (and prose in particular) remains an important tool for game designers because it's malleable,” notes Sheldon Pacotti, writer on Deus Ex and now at Spector's Junction Point, “One sentence can go from the Bronze Age to 21st-century Shanghai to the bridge of the Starship Enterprise. Imagine the development budget to represent that last sentence visually. Especially in adventure games, language is critical for conveying history, prophecy, and the multiplicity of a gameworld/society. Consider the dwarves' song about Smaug at the start of the Hobbit. It moves from legends about the dragon to a prophecy of its doom in a matter of seconds, and for me this is where the book suddenly becomes not just a story but a complete world."

"As the poly counts go up and the underlying technologies become ever more obscure," he continues, "I hope that game designers will strive to go beyond linear space-time. The rush of immediate experience is what makes video games unique, but it's also the medium's greatest liability. We need to do more with the past, with consciousness, with point of view. Many designers feel this, even if they aren't sure why, and that's why text didn't vanish after the advent of SVGA. Language is simply the cheapest tool for carving up space and time.” The reverse is equally true – while with enough of a budget, through montage or other effects, you can duplicate much of what words can do, it eats up time. For any amount of given time with the player, words can present a greater flow of ideas. While each of these may lack the impact of a single image, the developer can send barrages of concepts to send the player reeling. “We could accomplish many of the same things with cinematic techniques (montage, flashbacks, flash-forwards, narration) if we were willing to invest the time and money”, Sheldon notes. Time and money, of course, aren't infinite.

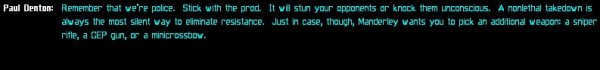

This has traditionally found its home in either role-playing games, adventures or games hybridised with those genres. Consider the most extreme – and artistically satisfying – example of what words can allow in recent times, Black Isle’s Planescape Torment, which crammed 800,000 words into a relatively short for the genre, but impressively dense, RPG. “We just thought that there was so much you could do with written description – facial expressions, motions of the hand, etc, that we didn’t have the art resources to represent,” remembers Chris Avellone, lead designer on Planescape: Torment, and now at Obsidian, “To do all the cinematics, animations, and movies to capture the memory sequences, companion expressions, and other moments just would have been impossible.” It also went against the occasional stated wisdom that text is just too much work. “I don’t think text is any harder to produce than building tilesets, models or doing anmations,” Chris, whose fellow designer Colin McComb credits as having written literally half of Planescape, adds “if you love doing it, it’s no work at all.”

Torment's also interesting in that most of the most important moments in the game only vividly appear in the text. To choose a memorable example, it’s a game whose “best” endings close with a conversation rather than the traditional open brawl with the end of game baddy. That these conversation trees prove so memorable is a testament to its power. “I think written descriptions of moments allows the player’s imagination to paint how the scene plays out (and fill in the gaps), and it ends up being stronger for it,” considers Chris, “The more you let the player bring to the experience, the better.”

An interesting parallel is the first generation of “Talkie” graphic adventures, while often extremely commercially successful, were often at the receiving end of the typical complaints that book-to-film conversions face in the multiplex: that the characters simply didn’t sound like how people imagined them. Text happens inside the mind, and so can be more personal. Of course, if a game is dense enough in words, it’s not as if there’s even the option of full voice-acting. Planescape, like many other RPGs, only voiced the first line of a character and the important scenes. “It was just a practical decision – there were just too many words,” remembers Chris, “but I think many people would rather have heard the game rather than read it. Still, voice acting wouldn’t have jived with the stage directions in the dialogue, however, which could have been jarring”.

Words can also carry meaning by their mere presence. Take the presence of English words in Japanese games, even those which will never be shipped outside of that marketplace. “The Japanese people see the US English with a very cool image,” explains games analyst Shida Hidekuni, “From the very begining of the game development in Japan, the developers used the poor English they knew at that time to make their game sound cool to users.” In other words, English text used purely as an aesthetic iconic form. “Even if Japanese people don't speak very good English (or not at all),” continues Shida, “they have a some kind of natural attraction to it. So English is used in everything in Japan, sometime with not much sense and often mixed with Japanese. If you look at ordinary devices like Fridges, the buttons are written in English. Games are only part of this cultural phenomenon.”

Words also have another subtle, indirect use. The modern world is, by its nature, packed full of words. You simply can’t avoid them. When trying to model a world, a way to add to the realism in a non-intrusive way is to include a selection of them. It’s the technique that been used to flesh out the more non-linear worlds of PC RPGs for time immemorial. Even if the players don’t read these background texts – and the majority of them really don’t – their presence creates the illusion of a more authentic world by implication. In the same way that that even though, outside of the Sims, no-one ever actually feels the need to use a toilet in their mechanics, their presence in a modern day office is required or the world would seem off. Even when they’re not being read, words are being seen and can make up an important part of the conceptual scenery. “In Torment, we had to give the illusion that the player was surrounded by thousands of dimensions and planes, even though he was only traveling to two or three,” notes Chris Avellone, “and item descriptions and stories NPCs told went a long way to making that more believable to the player”.

”It's somewhat telling, though,” thinks Sheldon Pacotti ruefully, “that we need to make an argument for language at all. I agree completely that some game developers need to be convinced even of the value of words. What I'd like to see is a growing awareness that game design itself is words.” Words exist in the superstructure of any gaming experience. Games are more than pure phenomenological reflex. “Good entertainment in any medium begins with words, which are the tools we use to organize thought,” he notes, “But most game design proceeds in a very chock-a-block fashion. In such an environment, words are just another system or feature, when what we should be striving for is a game experience that doesn't segment easily into different components.” Text is a tool, like any other available, and part of its charm is how it integrates and sublimates with all others. “How nice it is to play a game like Civilization, in which drama, strategy, text, and game mechanics all blend together seamlessly,” Sheldon laments, “It's like reading Erasmus or Proust. Such experiences are all too rare these days.”

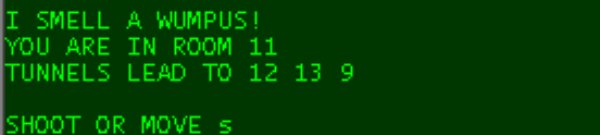

While words may be best understood in mainstream games in a holistic sense, as one of a game designer’s many multimedia tools, there is one corner of the modern games scene which it is dominant. This is the form which Graham Nelson, programmer of Inform whose release precipitated the modern scene, memorably described as "a narrative at war with a crossword puzzle". That is the Interactive Fiction – or “IF” – Community. Or, as they were known in the eighties, text adventures.

In the commercial sense, the text adventure was dead as the nineties rolled in, with the mainstream concentrating on the full flowering of Lucasart’s graphical adventures. However, like most of the eighties' forgotten genres, it lead to an underground cult of devotees collating on the newsgroups. Prompted by complaints that all the good games were in the past, Graham Nelson created Inform which allowed the creation of Interactive-fiction-masters Infocom-style adventures. Since then, with the simultaneous growth in popularity of the web, hundreds of adventures, of various sorts have been made, with Inform’s files are now capable of being run on interpreters for every system from the Oric to the Gameboy – and that’s not even considering the other alternative Interactive Fiction creation systems. Yearly competitions – such as IF Comp and the XYZZY Awards – provide a forum for new games to debut and be discussed. It’s very much a living community.

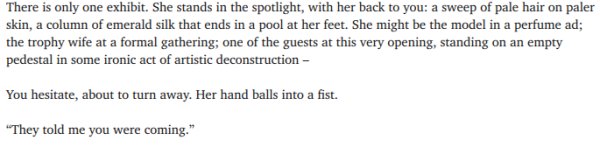

And the merits of the text adventure remain. They simply weren't necessarily supplanted by necessarily better technology – just more populist, accessible ones. “There's a great deal of beauty to be found in verbal expression,” notes Emily Short, IF author of critically acclaimed games like Floatpoint, Galatea and Savoir-Faire, “This sounds trivial, I know, but many of the IF pieces I like, I like for the writing: the rhythm of the prose, the attitude of the narrator, the wit or grace of the phrasing.” Having text as your only medium also changes the sort of experiences you make. “There are things you can write that you can't draw effectively,” Emily adds, “The reverse is also true, of course: graphics are superior at conveying spatial relationships, color and light, a sense of scale. But words are better at showing the subjective and the internal. It's hard to draw into a picture what the viewpoint character feels about what he sees; it's much easier to imply in a verbal description.” There's even simple utilitarian uses to text in play. “Words are handy for highlighting only the important aspects of a scene, and downplaying the unimportant ones,” Emily adds, “In a text game you can say "There's something glinting under the water", and the player knows 1) that there's something there he should be thinking about and 2) that he's not expected to know exactly what it is yet. I've played a few graphical games where I was scratching my head trying to figure out what a pictured object was”.

There's also advantages in terms of it being one of the longer standing genres. People understand them. “Having established conventions of form is freeing when it comes to content: because the author doesn't have to spend all his time teaching the player a new play style, he's free to cover some different and more surprising territory,” notes Emily, “How can we play with (or against) the reader/player's expectations? How can we use the form to express new things that have never been handled before? It's possible for those sorts of things to read as self-indulgent, dull, or obscure, but at their best, such experiments can have very startling effects. Adam Cadre has written a few pieces of IF that, like a good piece of stage magic, draw you in and get you to participate in something you fully understand only at the end.”

To choose a relatively minor, but clever, example – and we suggests you skip to the next paragraph if you’ve already been convinced of the worth of this work and plan on playing it yourself, and you can do so online in the following link – in 9:05 you find yourself waking up in the bedroom, covered in mud. A phone rings. You answer it, being told by a loud-voice that you’re late for work. What follows is a selection of normal morning tribulations as you get washed, ready and head to work. It’s only when you turn up in the office is it revealed that it wasn’t actually your house, and you were a burglar who fell asleep in the job. The contextual cues are enough to fool you completely. It’s an exquisitely told short joke, but this sort of trick has been used to examine a far broader range of emotions.

It’s also possible to play through in a quarter of hour break from work, which is another interesting trend in the community. Not all games are novel-sized epics, with short works – either as a polished narrative unit in themselves, or to explore some coding possibility to allow better future games – relatively commonplace. Equally, it’s also a hard game to “lose”. The IF games spread along the whole range of possibilities between the dual poles of cross-word puzzle to narrative, with there being some examples where you’re dragged through the story, no matter what you do. Even in the most extreme cases, however, there’s a uniqueness to its approach that make the even nominally interactive IF compelling.

“I suspect that most people involved with IF got into it because they really enjoyed the IF works they'd encountered back during its brief window of commercial viability,” Cadre argues, “I didn't. I liked some of Infocom's outfit (at least once I equipped myself with hint books so I could actually get farther than a few moves in) but the only piece of commercial IF that really captured my imagination was A MIND FOREVER VOYAGING. I had never given a thought to writing IF until I discovered Andrew Plotkin's A CHANGE IN THE WEATHER on Infocom's MASTERPIECES CD, and I thought, "Hey, you know, I bet I could use this medium to create a different sort of thing..."

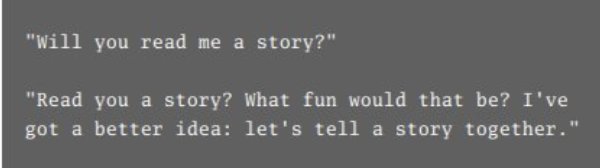

Where is the community going next? “The thing about IF is that its creators can face whichever challenges they want,” notes Emily, “There's no marketing department. IF tends to evolve because specific people decide they want to try experimenting with specific things that have never been done before.” She focuses on areas such as accessibility, plot branching – a difficult thing to do with a modern budget, but relatively trivial in non-intensive text – and better characters.

“Characterization has come a long way in interactive fiction,” she adds, “So has plot delivery. The economics of a graphical game may be against widely-branching plot; text costs less, so that it's easier to justify writing more scenes and endings than any one player will ever see. And much modern IF combines genres or defies genre categorization entirely; instead of having "a horror game" or "a mystery game", you find games (justifiably!) catalogued as, say, "Science Fiction / Mystery / Historical / Horror / Indescribable / Experimental / Religious / Existential / Surreal". IF written as an experiment may not itself be very interesting to gamers with only a casual interest in the medium, but those experiments eventually lead to a much better understanding of how to convey dialogue, or involve a player in a complex landscape, or do any of a number of other things that are useful in a robust, well-designed story or game. Recently we've seen some very exciting new IF, stuff that shows a maturity of technique that comes from years of toying with the possibilities.”

Adam Cadre, however, is more downbeat: “I imagine that it'll probably gradually die off again. I suspect that most everyone who would be inclined to take a crack at IF has already done so. I know a lot of people who wrote a game, often a well-received one, and that was pretty much it; they'd gotten it out of their system and had no inclination to write a second one.” Emily Short is more optimistic on this point, “I really don't know how long the community will last,” she argues, “But there are still new people becoming interested in IF who have never tried it before; this is pretty evident from the newbie posts on the newsgroups.”

Over in the mainstream, expectations are even lower. Will anyone go as far as Planescape did in the future? “Probably not,” opines Chris Avellone, “I think a text heavy game is a tough sell to any publisher now, and even so, most games coming up are focusing more on voice-acting, which is probably better for the player. As an example, working on Knights of the Old Republic 2: The Sith Lords requires that LucasArts and us here at Obsidian manage a great deal of voice recording, and while it doesn’t have the freedom of text, I think it’s pretty powerful to hear characters actually delivering the lines instead of reading them. It’s just a LOT of work.” In fact, voice-acting actually supplants writing, just because it can convey more information. “When you have the right voice actor, you (1) have to say a lot less for production reasons unless you are filthy rich, and (2) you don’t need as much text as to get your point across – the character’s voice and tone alone can say a great deal,” Chris adds.

So does that mean the writing’s on the wall for writing? In the current industry model of more-Hollywood style games, some of their traditional roles will continue to be usurped by speech. That is, the spoken word triumphing over the written one. However in certain areas, either inside games as context or as underground games, they’ll continue to work their special magic. After all, we’re not bored of words yet. Or, at least for this text-based blog, we kinda hope so.