Outcast (Reprise)

Originally written for the UK's resplendent Edge magazine, this look at action adventure masterwork Outcast features a handful of retrospective comments from one of the key developers from the project, Yves Grolet. Mr Grolet was one of the founders of French Belgian development house Appeal, and was one of the key proponents of third-dimension bearing pixel, the voxel. Grolet is now a senior games bloke at the dubiously named 10Tacle Studios.

I've given the original text a spruce up by replaying Outcast, and erasing almost everything I originally submitted... Because there's nothing quite like rewriting history. Read the entire thing by clinking that the link, down there. Yep.

The Outcasts

Made up words are one of the routine hazards of science fiction. Outcast was chock full of multisyllabic titles, places, and awkward names for alien ostriches. Ask a veteran of the game the first thing that they remember about it and it might just be these contrived concatenations of vowels and consonants. It's was a small joke among journalists of the time that Outcast's characters had to pronounce quite so much unlikely gibberish, making reviewers feel that something like a Klingon dictionary was just a successful game launch away. Fortunately Outcast was a commercial disaster, so no such alien codices were forthcoming...

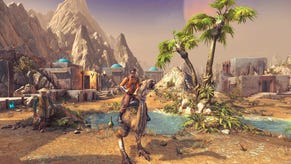

Nevertheless these verbal absurdities were just one facet of one of the most ambitious attempts to create a cogent, living, breathing world for players to explore. In fact, the first thing an Outcast player is genuinely likely remember is the comparative scale and the exceptional breadth of freedom that the game supplied us in 1999. Outcast's many different lands, from desert to swamp to icy tundra, were utterly free to roam, and occasionally well structured enough to set the player on the road of an epic quest to save both his colleagues and the entire world. (Incidentally fixing the small problem of a continent-devouring black hole, back home on Earth.)

Despite the fact that an errant singularity was eating our homeworld, players were encouraged to take their time in exploring this new planet. In so doing we were able to build up a reputation among the peasants and rebel clans for whom our hero, Cutter Slade, was something of messiah. Outcast's towns, villages and alien wildernesses remain one of the outstanding visions of what PC gaming could and should be like: it was a game of exploration, and of gun-fights in rice-paddies. Outcast took an extraordinarily open-ended approach to a serious sci-fi universe - with characters going about their own business, and AI beings reacting to your whims - while simultaneously allowing a storyline to emerge through the player's interaction with complex scripts. Its a rare feat indeed.

I spoke to one the founders of that original Appeal team, Yves Grolet, to ask him a few questions about what he'd got up to in the years leading up to Outcast's completion. Grolet was already a veteran of the French games industry at that time. Having started out as a programmer for Ubisoft at the age of nineteen, he went on to jointly found the development house Appeal in 1995, working on Outcast until its release in 1999. In 2002 he launched his own company, Elsewhere Entertainment, and has subsequently joined 10Tacle.

Clearly Outcast was important game for Grolet personally, but why should we regard it as an important game in the great celestial scheme of gaming? "I think it was the first game with an open-ended 3D immersive world that the player could explore at his own convenience, at his own pace and in the order he wants," explained Grolet. "It was also the first time that a game blended action and adventure in a seamless manner and without scarring either of those two components."

Grolet's not kidding. Outcast's alien planet was populated by a vibrant culture that swept from peasant-filled fields to grim and dusty deserts. Once the tutorial (infamous for its near-impossible stealth training) was out of the way, players were able to access any of the huge terrains that made up the game's different regions. Go anywhere, talk to anyone, you just had to stay alive long enough to unravel the bigger mysteries. Working with the natives against their oppressors was an huge task and keeping people on-side took some work, even for the most dedicated adventurers. For Appeal this meant a massive effort in scripting conversations and creating bug-free AI for the alien peoples.

Grolet was keen to emphasize this point: "Outcast was a game that featured an alien world that appeared alive with citizens "living" their life during the game. The AI was one of the most difficult parts to develop because the citizens had to do their job, react to the player missions, react to the player reputation and also react to danger and combat happening around them. The difficulty was to have the citizens prioritise and select the appropriate behaviours at any moment of the game."

For the most part this approach was extremely rewarding. Even more recent games such as Morrowind (or Oblivion) have struggled to provide such a sophisticated and believable game world – one in which NPCs aren't simply mannequin conversations waiting to happen. Grolet is justifiably proud of his team's success in making people feel like they could approach a living world in any way they saw fit. Even massively multi-player games have not yet reached the same level of complexity and believability that Outcast achieved with its reactive, active alien persons. Watching peasants flee as a battle erupted was peculiarly authentic - almost as if what matters most isn't how sophisticated or pretty the residents of digital worlds are, but instead how we respond toward their actions. If they flee like animals, and potter about like animals, then they must be alive.

Nevertheless many gamers were put off by odd visuals and uncertain purpose, as Grolet concedes "The biggest failure is that the software rendering appeared a bit outdated at the release of the game." Appeal had made the peculiar decision of employing voxels, the 3D pixel technology made infamous by Novalogic's Comanche and Delta Force games. The 3D card revolution that was taking place around the development of Outcast meant that traditional polygons leaped ahead in sophistication, leaving the CPU-dependent voxel system looking clumsy and outmoded. "At the beginning of the development of Outcast, 3D cards did not exist," says Grolet. "We decided to use voxels because it was a method that allowed us to render realistic natural landscapes. We decided to render landscapes instead of indoor environments because it was refreshing and different from the other games. Moreover, natural landscapes were a richer source of inspiration for us to make a world that allowed the player to dream about epic adventures."

Outcast's rolling landscapes and wondrous water effects did indeed entrance many gamers, but (with the exception of the rippling water) it simply didn't stand up to the likes of Id Software's Quake technologies for sheer visual impact. "The difficulty we encountered with voxels was that the image cleanness was not as good as the ones rendered with 3D cards that started to appear during the development and dominated the market at the release of the game," explained Grolet. "We had to face a transition of technology and we decided to stick to our initial choice to stay coherent with our vision of huge and detailed natural landscapes."

It was a brave move. While Voxels did have some major constraints, particularly on how detailed the models for the game characters could be, it did allow for a landscape of a kind of size and complexity that are only just being achieved by polygonal approaches today. Of course for gamers who'd just invested in shiny graphics cards it wasn't really an option to fork out on new a CPU for a quirky French adventure game, no matter how impressive its ambitions. Voxels fell from grace, with Outcast looking like their death knell. Subsequent CPU power increases mean that these unusual 3D tools might one day make a return, perhaps in further hybrid approaches like that of Black Hawk Down, where Novalogic mixed voxels with mainstream polygonal models, but they were not to be used for Outcast II, a game for which Appeal would take quite a different, and ultimately fatal, approach.

With critical success and a small but enthusiastic fan-base behind it, Outcast was set up for a sequel, but Grolet wasn't to be a part of that doomed project. "I quit Appeal at the beginning of the development of Outcast II because I did not agree with my ex-associates on the way to handle Outcast II. I would rather not give any details here. Unfortunately, two years after my departure, Atari (then Infogrames) decided to cancel Outcast II. It was a sad decision that disappointed everybody."

Yet Outcast still persists on the fringes of PC gaming, a part of the free-roaming adventure lineage that stretches from the ancient 3D adventure Midwinter right up to present-day offerings such as the Stalker and Oblivion. That there internet has proved a haven for the iconoclastic 3D adventure, with an effort to create a sequel to Outcast being undertaken on an open-source website, where fans of the game have taken on the old voxel engine and attempted to give it new life with their 'Open Outcast' development project. Point your web browser at www.openoutcast.org to check up on the continuing legacy of one of the PC's finest creations, including a tech demo of the Outcast remake available to download and, well, walk about in.

You can pick up Outcast on budget, or from Amazon for a couple of quid, and I think it's worth doing. It's neither gone, nor, in my mind at least, forgotten.