Wot I Think - Torment: Tides of Numenera (for series newcomers)

For those new to torment

You do not know the past of Torment, and so chose to hear everything.

No, you don't need to have played 1999 weird fantasy roleplaying game Planescape: Torment to enjoy this spiritual sequel. There are references and commonalities, but they're not in any way necessary to understand or appreciate it. What is required is a reasonable degree of patience, and an enjoyment of reading and of big ideas.

To summarise as briefly as possible: this is an RPG set in a world of equal parts magic and technology, and at which the relics and detritus of other worlds and realities have washed up. You, as a male or female character dubbed 'The Last Castoff' are born into it in adulthood, with apparent ties to a divisive 'god', and from there you must uncover the secrets of your own past, but more importantly make an ongoing choice about who you wish to now become.

Torment: Tides of Numenera does contain action, and many of its situations can be resolved with violence if you so choose, but to do so would be to cut yourself off from the game it most wants to be. The game is one of obtaining as much information as you can, and then making decisions with often far-reaching and sometimes tragic consequences based on your analysis of that information.

I don't mean simply moral decisions here, but also that Torment will drop hints about possible solutions in its dialogue, leaving it up to you to put two and two together about how you might resolve its many quests or dilemmas, and the possible consequences thereof. This is an RPG for attentive players, not those who merely wish to accumulate increasing powers of destruction.

Think of it as the dialogue-based decision-making of Mass Effect or The Witcher, but expanded enormously, with far more scope to elicit further information before choosing your actions, yet also avoiding obvious binary nice/nasty choices. An empathetic choice is not always the best choice, while slaying an apparent villain might well close rather than open doors.

Simple morality is sidestepped via the titular Tides system, which effectively sees your character's personality defined according to your various and ongoing actions. A gold character is one who has tended to be sympathetic to others and self-sacrificing; blue prides knowledge all else; red is impulsive, whether driven by passion or aggression. Your Tide(s) will shift as you play, and attempts to be one sort of person may be foiled by making difficult choices that favour society over the individual or vice-versa, or yourself over others, or vice-versa.

Though your Tide has only subtle effects on how others respond to you, the messages that denote changes to it does become something to personally strive for - to feel relief that you have done what you feel is true to you, or horror that you may have gone against your nature. Additionally, tending towards one behaviour or another is likely to lead to consequences that other Tides will not experience. On paper, Tides are comparable to the Alignment system of Dungeons and Dragons - lawful evil, chaotic good and all that. Here, though, they are mutable across the course of the game - this means you create your character as you play more than you do finesse an established template over time.

By contrast to that, Torment drops new players in at the deep end, with a torrent of unfamiliar terms in character creation. With a few exceptions (for instance, the choice between, essentially, a wizard, a warrior and a bit of both archetype, which is primarily a combat rather than behavioural factor in any case), there's plenty of scope to drag your character in a different direction if you don't feel comfortable with what you initially rolled.

This is not true simply of being able to divert your skills into other areas (mechanical prowess or charisma, for instance, instead of combat-related abilities), but also that, in any dilemma, you can 'spend' your pool of key stats on increasing your chances of success. This is known as the Effort system, and it means that even if, say, you only have 1 point of Might, you can spend that to potentially succeed at smashing open a box or prising a scale off a weird psychic cube.

You'll get it back when you rest or use particular items, or maybe one of your party members has the points to spare instead, so you're never locked into anything for too long - go with your gut and you'll find a way to succeed. This is, in many ways, an RPG that's far more about you and what you want than it is about the story it seeks to tell.

However, Torment is deeply invested in the story of its world, the story written around the edges of your decisions, and at times this can be to its detriment. The first hour browbeats players with fictional terminology and elaborate lore, though this eases off thanks to a combination of combing some understanding from it and gradually accumulating more personal goals and connections. Throughout though, Torment can seem more interested in a forensic examination of its many ideas about the philosophy of the self and the knotty problems of faith than it is emotional resonance.

The central character in particular, a body once occupied by a mortal god but which has seemingly taken on its own identity since said deity moved on, can come across as even more of a cipher than he or she is (clearly deliberately) intended to be. Though others may find themselves following lines of conversation and thought that I never even saw due to one choice or another, I did find that this character's dialogue options tended towards endless inquiry about the fiction of the world rather than their own feelings about their bizarre state. The central plot has similar artifice, with a couple of key reveals coming across as an abrupt gotcha lurch rather than the earned emotional rug-pulls they're intended to be.

Similarly, some party members (of which you can have up to three at any one time) seem too obviously defined by their admittedly inventive central conceits - the woman who is surrounded by the flickering, ghostly shapes of her alt-reality selves; the man with the mysterious living tattoos; the bizarrely ever-cheerful guy with a body-wide halo - rather than how their relationship with the player might build. For instance, another companion character is, avoiding full spoilers, a sort of sister to yours, but there are vanishingly few options to explore the strangeness and importance of this. It's just an accepted fact, treated as less interesting than the external dilemma that preoccupies that character.

Other companions are much more successful, with either more of a sense that they are real people in this world rather than walking concepts or because their relationship to the player is evolving and with long-term effects. One, in particular, has a glorious pay-off, which many may not see because of how this person is presented for the bulk of the game. Torment rewards persistence most of all - also shown by the way seemingly incidental side-quests sprout true and meaningful results far later on.

Much of this game, its world and its story hits harder in hindsight than at the time. It is most successful in how its questions - and your actions in response to them - resolve, whereas at the time some can seem like uncertain wandering or grinding through conversations with a endless army of characters. This is not true only of how factors both big and small come to bear in the end-game, but also much earlier.

There is, for instance, a tavern early in the game, in which every one of its ten or so characters offers vast amounts of conversation. To start with, most of these seemed like incidental flavour. After a time I began to see links. Then I made discoveries. Then I saw new things entirely (literally). I must have spent an hour and a half just in that one alehouse, resolving one deft and interwoven mystery that involved everyone inside it. On the surface, I was just running back and forwards across the same room, to the same handful of characters. In my head, I was metaphysical Poirot.

Torment is often like this, the seemingly incidental turning out to be the tip of some immense and intricate iceberg. What I loved most about it was losing myself to it. Entering a new area, cracking my knuckles, knowing that there would be so much to dig up here, and that, when I left it, it would be profoundly changed by my actions. Quite probably without a single body hitting the floor too.

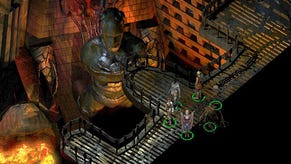

It's frequently a beautiful game too, although its rather simple 3D character models are not at all the equal of its lavish, painterly environments, while the UI is not entirely elegant. Though many of Torment's strengths are in the images and agonies it conjures in the mind, it is reliably a delight to enter a new area and slowly unpeel the gloriously strange sights within.

It has its pacing issues, does Torment, and sometimes it can be too preoccupied with showing off the quality of its ideas and language over and above getting its emotional hooks in. Nevertheless, this would be considered a triumphant, wildly inventive and highly reactive roleplaying game even if Planescape: Torment had never existed.

Torment: Tides of Numenera is released today for Windows, Mac and Linux, via Steam, GOG or direct from the devs.