Wot I Think: Surviving Mars

Sim City amongst the stars

I shed a surprising amount of tears during the founding of my first red planet colony in Surviving Mars. None of those tears had anything to do with the pipe leak that killed 58 people, I hasten to add. For those, I just swore at my repair drones and made more colonists work gruelling night-shifts at the polymer factory so we could patch up the air tubes.

My tears, I'm afraid, came instead at testaments to my own magnificence: when a dusty patch of sand patrolled by listless worker robots and automated factories saw the construction of its first bio-dome, when the first humans from Earth arrived to stake out a new life in this place I had built for them, when the first non-Earth baby was born. Live inside my work, ye Martians, and try not get caught inside a meteor storm.

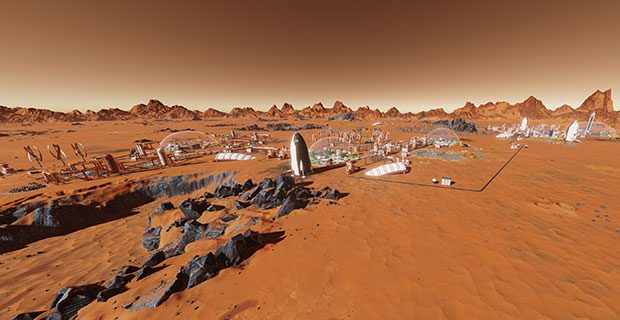

The elevator pitch for Surviving Mars is Sim City (or Cities: Skylines) on a near-future red planet. It's a town-building sim but in a place that initially has no oxygen, water or food, and in which freak weather could mean a total wipeout of an ill-prepared colony.

Surviving Mars is almost entirely based on theoretical science and, like Andy Weir's The Martian and its film adaption (which it owes a few inevitable debts to), occupies a 'five minutes into the future' time period. It is very much about the nuts and bolts of, well, surviving and Mars, and that begins with preparing a section of the planet for habitation far in advance of sending over the first colonists.

You'll spend your first few hours scratching about in the dirt with a handful of remote-controlled, semi-autonomous drones which can scavenge basic resources and turn them into windfarms, solar panels and powerlines which can in turn power the likes of fully-automated mining equipment. This section of the game lasts several hours, and during that time it feels as though it is the game - gradually transforming this small tract of Mars into a self-sufficient factory. It's slow work, and lonely work, and it's also Surviving's Marsterstroke.

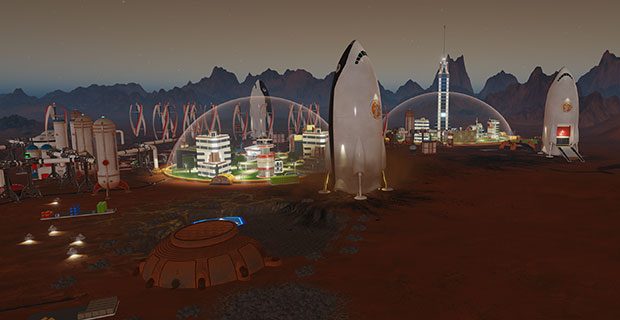

When the time finally comes, when enough concrete has been painstakingly harvested to build basic water and oxygen capture systems and then, yes, oh god, an honest-to-god dome, it is absolutely glorious. The transformational effect on the scene you've been staring at for hours, as this huge swathe of blue, green and silver suddenly squats amongst the red rock and dust like an invading jellyfish. And then the transformational effect on your mind, as suddenly there is this new raft of things to worry about.

Build living quarters and hydroponic farms, connect everything with these thick rubber pipes, up the electricity supply dramatically, and request supply ships from Earth to provide resources such as electronics and polymers that I could not yet produce myself. And then... And then the first passengers from home. The first colonists. The first Martians.

This middle-section of the game has several moments during which I positively fizzed with pride. As mentioned previously, when the first child - the first true Martian - is born. When the first native supply line of metals or polymers is established by those brave pioneers. The first time I created enough fuel to return one of the supply ships back to Earth. When the second dome, this one containing a school for my colony's growing second generation, went up. The creation of my first gleaming spire, the population's growth to 100...

It's an attractive game (with a good soundtrack too), but more importantly it's fairly adept at keeping superficially complex elements manageable - all these different resources, the distribution of drones across networked hubs, the sealed domes that behave almost as individual cities, and most of all the cables and pipes that act as a nervous system for the entire colony. That's essential for any good city-builder: yes, many plates must be spun, but clear labelling of which is which takes away a lot of the pain. There is some jank to an interface nowhere near as slick'n'sexy as its stablemate Cities: Skylines, for instance some inconsistency about left and right mouse button to give orders, deselect drones or bring up the build menu, but by and large I didn't have a problem finding the information I needed.

Which is just as well, as in the wake of polluting the empty planet with people, I very quickly needed a whole lot of information a whole lot more often. Drones don't need to breathe, drink or eat. They get all they need from a single powerline. Humans? Humans need so much. And they have these frail little minds that freak out at the solitude or begrudge their accommodation or get addicted to substances.

Oh, and they die. Sometimes in very large numbers.

There's this unspoken suspension of disbelief in any city-building game that some offscreen authority has chosen you as the most qualified entity for the job, that you must have some fantastic off-screen career which informed this. In an earth-bound town management game, the nuts and bolts of laying down rows of houses and waterpipes is straightforward enough that this fantasy is broadly undisputed, but it gets more complex in Surviving Mars.

It's hard to swallow the idea that NASA would have sent in someone who doesn't already know innately that it's not enough to merely be generating sufficient oxygen, water and power, but that vast excesses of it must also be stored in order to provide sols-long backup supplies in the event first one, then two, then three, and at one point five utility pipes burst.

When the pipes burst, 58 people died. They died because I had no contingency plan, because no powerlines or waterpipes had failed during my early hours in the dust with those drones and so I had assumed they were wear-proof, because the lines that failed cut off power from the factories that made the resources required to fix the breaks, and from the hubs that commanded the drones to enact the fixes. It was a terrifying, mortifying domino effect, as more and more of my colony went offline, taking more and more of capability to respond with it, as more lives were lost either to the elements or as suicide to escape the worsening horror.

The only reason my couple of dozen survivors didn't join their comrades in fertilising Mars' barren soil is because I managed to summon a rocket from Earth, packed with building materials and expensive pre-fab, instant constructions, just before the lights went out forever.

I recovered, eventually, slowly, painfully, but it was never the same. My new home had betrayed me, and I had proven myself a poor leader of a new culture. I readily accept this a component part of Surviving Mars' The Martian Fantasy. Like Mark Watney losing all his potatoes, if I'd had an easy ride it would have been a boring, easy story, and inappropriate for the scale of what I was trying to accomplish. On the other hand, my disaster speaks to some flaws in Surviving Mars that I hope future updates could address.

There is no option, for instance, to make your drones prioritise patching a broken cable or pipe - you can assign high priority to a malfunctioning building, but no such button exists for the vital blood vessels which link them. And so my drones fiddled while Rome burned. Insult to injury is that fixing a damaged cable or pipe takes significantly longer than flat-out building a new one does - but no matter how many additional or parallel lines you lay, one going down still robs the entire network of vast amounts of power, water or air. What I'd give for a roll of duct tape.

The way to roll with these punches - and, in the mid-game, the cable/pipe breakages come thick and fast - is to have massively over-generated and stored electricity, water and oxygen in order to weather not just the occasional meteor storm, but more importantly just general wear and tear. Another option is to having your colony neatly ghettoised into self-contained networks, so one area's power going down doesn't cause everyone in a dome on the other side of the map to freeze to death.

This is all relatively easily enough done if you know about it in advance, and I do to some extent appreciate how much I learned from the calamity, but it was gruelling to have so many hours' work destroyed because of something the game had done a poor job of explaining. Still, second time around I'm going to have a very different experience, which I am glad of. I will build my colony in neat, self-sufficient modules, no-one will be summoned from Earth until I've stored up enough utilities to power a small city for a decade, and I will fast track the branch of the Civ-like research tree that eventually leads to maintenance-free electricity cables. On the other hand, my first dome, my first colonists, their first baby - none of that can feel as momentous a second time around.

All this, I hope, conjures the sense that Surviving Mars has broadly done its job - to hook me deeply into its construction and maintenance, rather than to repel me with jank and grind, as is forever a risk with a game of this sort. There are some edges that need smoothing, and I don't feel it does much interesting with the colonists themselves, despite random assignations of specialisms and peccadilloes - which is why I haven't really mentioned that stuff. There is min-maxing to be done, but for me it was just a matter of having enough people to work all the farms and factories.

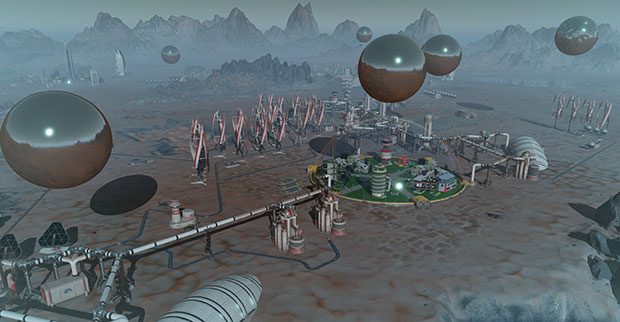

A far more significant curveball are 'Mysteries', openly science-fictional discoveries that can trigger a chain reaction of choose-your-own-adventure and massive disasters. Like everything else in Surviving Mars, these are slow-burn and primarily about making the ongoing maintenance of your base and its resources even harder, so do think twice about activating one. (If you can figure out how - the notifications that one has been found don't tell you where it is, so you have to scour the map yourself). They can introduce new important new techs if you can weather their storms, and some spectacular sights, like the below, which I present without comment in order not to spoil how it plays out, but what they primarily do is disrupt your plans on a massive scale.

In my experience, they're best tackled when you're in a comfortable holding pattern and actively want to escalate the situation - or just want to watch the world burn. Or freeze, as the case may be.

Another reason to hold off on them is the Surviving Mars' construction side did get a little listless once the third or fourth dome went up and it started leaning into expansion purely for expansion's sake. A fairly staple issue with city-builders, that, but the Mysteries can definitely remix the late game if you choose to.

My most abiding concern is replayability - I don't really fancy going through the very slow early hours all over again in order to get to the bigger picture stuff once more, and the inflexibility of all those pipes, wires and domes does place a certain ceiling on how much you can visually design your Martian cityscape. There's not much of the 'oh, I fancy making a city bit like this...' of Cities Skylines, say - there is no space for such frippery when lives are so much at stake. Still, though I sometimes grew weary of the donkey-work of cables and repairs, I definitely relish the new state of sustained fear Surviving Mars brings to city sims. It means that even small accomplishments feel so much bigger.

Surviving Mars is out today on Windows, Mac and Linux via Steam, GOG and Humble for £35/$40/€40.