"There’s space in the medium for ultra-hard games." - Below and the difficulty in crafting difficulty

Dopamine mine

"Under the hood, too many games are just primarily about finely-tuned reward systems. Nothing more than expertly crafted dopamine injectors which often border on, if not fully embrace their Skinner box-like qualities."

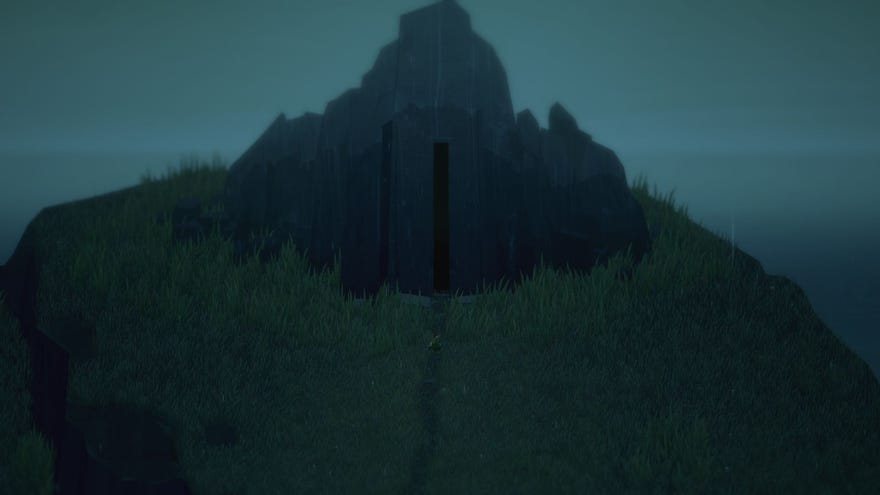

Kris Piotrowski didn't want to create a game like that. As the creative director and co-founder of Capybara Games, he and the team spent years working on Below, a roguelike in which you steer a tiny person to explore a labyrinthine cave. "Players have been trained to expect soft padding around their games, but if they don’t pump the brakes and take it slow when they begin venturing deeper into Below, if they don’t play carefully, if they don’t prepare their backpack for deeper exploration, then the game eats them for breakfast."

The problem: a lot of players didn't like being eaten.

Reading reviews of Below online turns up a few recurring criticisms, as people seemed to either find its difficulty far too frustrating or its mysteries much too vague, or both. In our own Below review, Alice wrote that, "The game seeks to punish risk, but in the terrible cage match of risk vs. repetition, risk throws repetition from the top and sends him plummeting 16 feet into the announcers’ table every time."

Between its challenging combat, punishing survival mechanics, brutal permadeath and very slow pace, Below undoubtedly has a lot of barriers to entry. But a difficult, unforgiving and unloveable game? There's nothing I like more! I was hooked from its first fifteen minutes, in which Below conjured up more questions than the vast majority of games I've played in the last few years.

That's why I wanted to talk to Piotrowski about the design decisions so many people had struggled with. That started with the game's introductory cutscene, which is so long that people start wondering if they're supposed to press a button to properly start the game.

Piotrowski explained that the long, slow opening was important to establish the tone and to hint at the intended pace. "In Below, the fastest way to find death is to run directly into darkness or charge directly into a group of monsters." The cutscene is telling players to slow down. "But really, I just have always dreamt of a slow, long zoom-in sailing sequence for the opening. I fell in love with that idea," he said. "I wanted the opening to cast a spell, to hypnotize the viewer like a spiral..."

Piotrowski wanted players to feel very alone on arrival, exploring the barren surface of the island and finding nothing but the lantern. This naturally leads them to begin their descent into the island's interior.

For all its opaqueness, I found a lot of Below’s elements intuitive. The crafting in particular has a charming ease to it, with little trial and error. Some of it makes plain sense - combining hot water and some vegetables gives you soup, for example - but the system also offers the surprise of what more unusual combinations will give you.

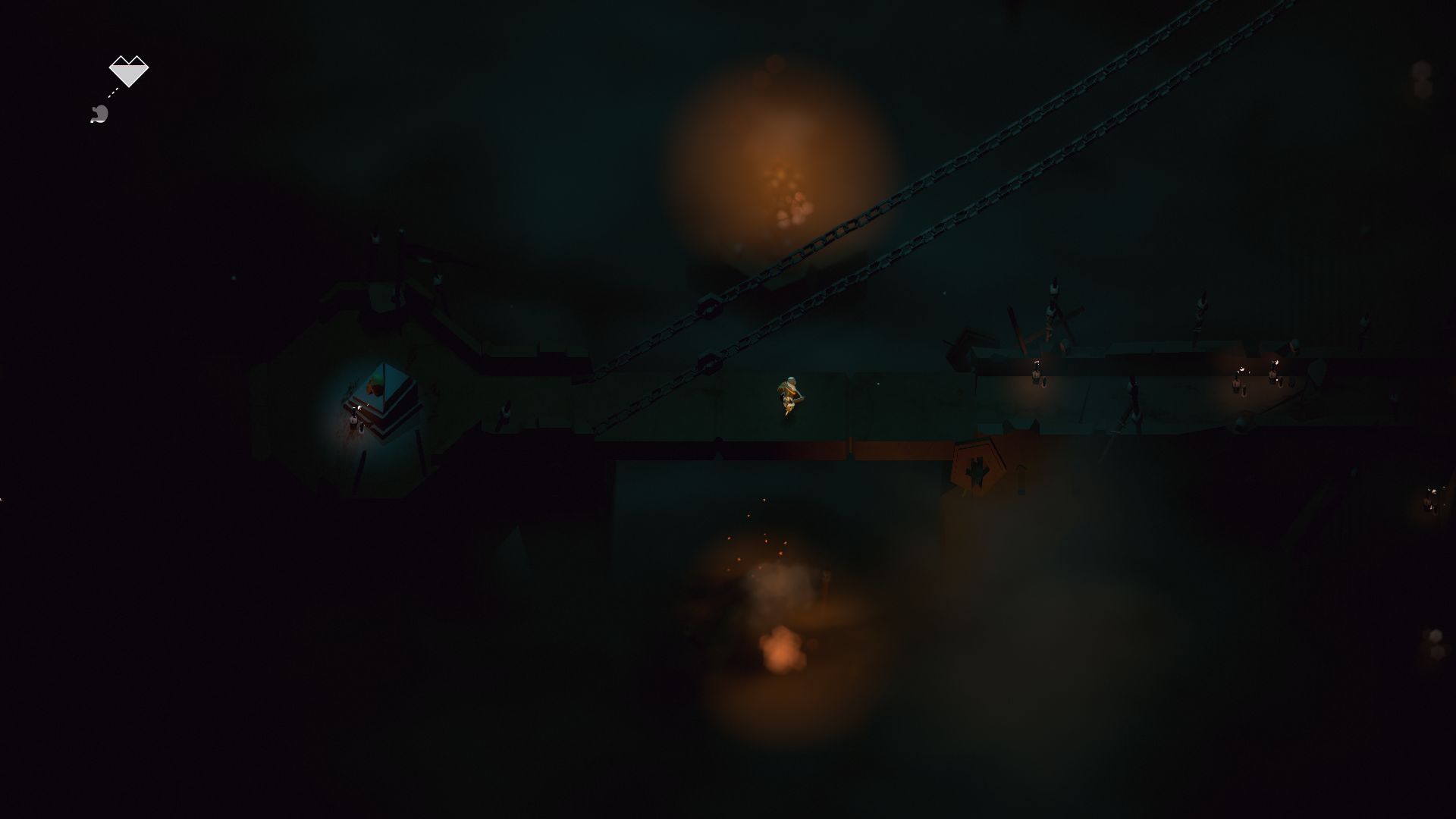

Piotrowski explained that while the player gets barely any hints, the controls the player can use are never hidden. Below has campfires, for example, that you can use as a checkpoint or shortcut by sacrificing gems collected from enemies to turn the fire blue, but you’re never explicitly told this. "We thought it was enough to include a UI element in the Campfire menu, and then just let players try to use it to figure it out," Piotrowski said.

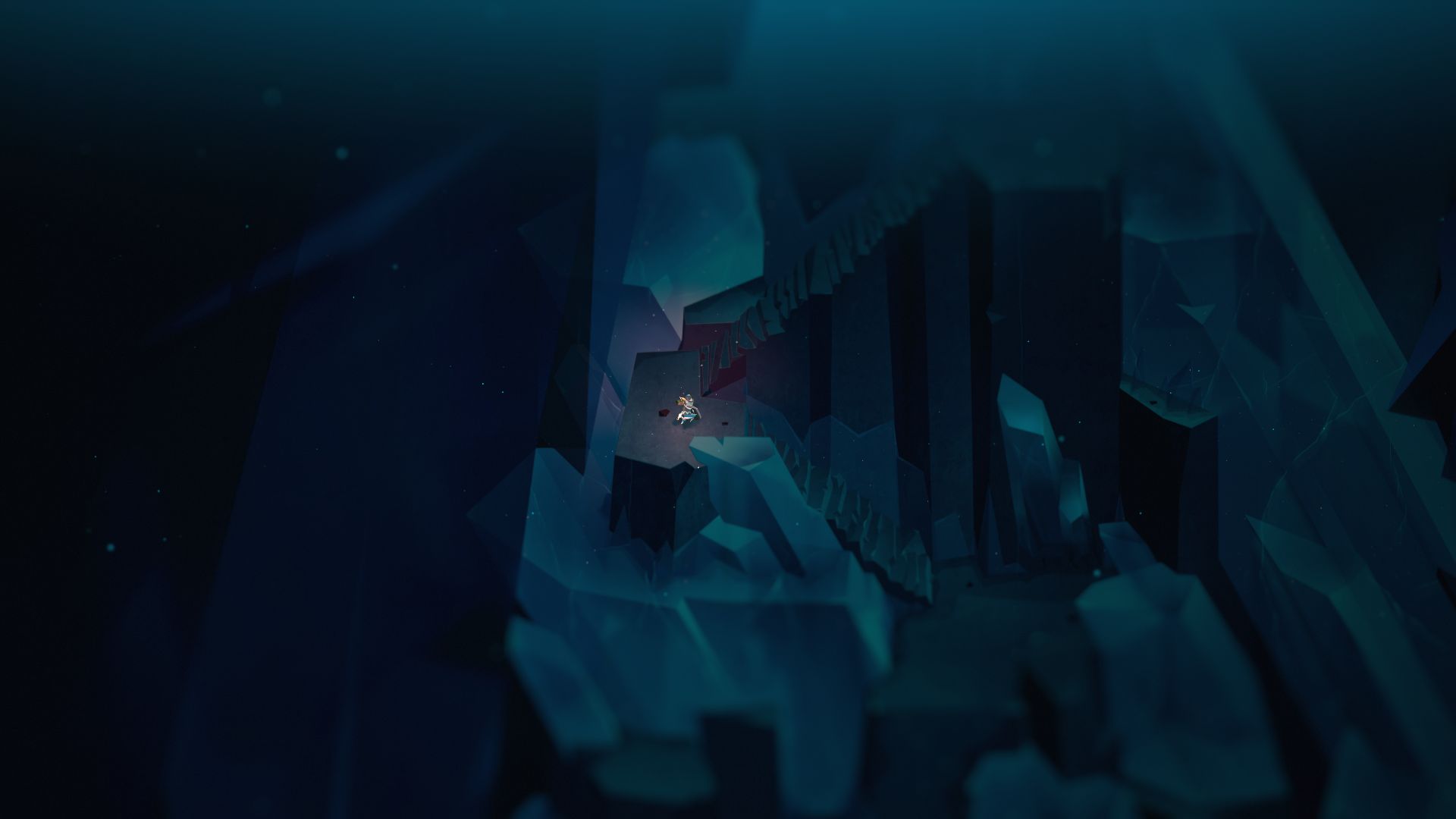

This meant I got completely swept up in sticking my nose around those caves and trying out things. Those initial labyrinths crackle with magic and mystery. Just overcoming the basic obstacles of seeing in the dark or figuring out how to fish had me hooked. Every little step in this game is an act of discovery - aided by the caves themselves, which are partly procedurally generated.

I knew some amount of generation was involved in Below, but I couldn't tell which parts by simply playing the game. To be honest, all of it seemed laid out by humans hands to me.

"The game world is composed of randomly generated dungeons and cave layouts, which contain within them handmade secret areas," said Piotrowski. Contrary to what I had thought, the majority of the game is randomly generated. Some key locations, like an unsettling grave of identical shipwrecks from past expeditions, are fixed, but the caves to get there aren't. "If the line feels blurred, hopefully it’s a testament to the artists' and programmers' hard work making the random levels look and feel as close to the hand-crafted sections as possible."

The random generation is another element that serves to make the game harder, since you can't memorise locations. That's a big disadvantage when one misstep can get you instantly killed on a spike trap, and most enemies hit harder than you do. I asked Piotrowski if he felt they got the difficulty balance right.

"I committed pretty hard to creating an unforgiving game. I thought that difficulty was important to the experience, a big part of the theme from the start, and that’s something about the game design that I couldn’t compromise on."

Piotrowski thought it was important for the game world to try to keep the player out, to fight to protect the long-buried secret at the heart of the island. "I think there’s space in the game medium for ultra-hard, weird, or obtuse games," he said.

For contrast, Piotrowski isn't at all interested in making the kind of dopamine-feeding games we mentioned at the beginning. "I find these types of game experiences fundamentally disgusting and problematic, but like most people, I also can’t help but ‘play’ and ‘enjoy’ these games as well…" he said. "However, I think that there is an audience that craves the carbon opposite: a game that you play on pins and needles, where a wrong move can cost you everything, where the desire to play comes from the feeling of gaining comprehension, genuine skill improvement or just to experience pure wonder. Where the purpose of progress is not defined by receiving your next dose of dopamine hidden inside a treasure box."

This desire has been the foundation of Capybara games for a long time, right back to Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP, which very much feels like Below's spiritual predecessor. The manifesto produced by one of their collaborators on that game, Superbrothers, feels like it still sums up a lot of Capy's philosophy behind Below: Less Talk, More Rock.

That said, development wasn't a straight shot towards the finish line. "I originally set out to tell a different story, but as the production of the game dragged on and become more difficult, my mental state took a tumble, and along with it, the ideas I could convey changed," Piotrowski said. He explained that he has a hard time "decoupling" himself from a project he’s working on, meaning that Below became darker, harder and more unforgiving as time went on. But regardless of where the project went, Piotrowski always wanted to create something that allowed interpretation.

"We have always tried to make games that aim to capture a specific audience, rather than attempt to make vanilla games for everyone," said Piotrowski. "I like complexity and I like to lean into the weirdness, lean into the friction and find ways to sharpen the prickly edges of the game’s design. I tried to do that with Below, for better, or in hindsight, maybe for worse. That being said, I think my next project will be something soothing."

Below is clearly not a game for everyone, and it undoubtedly succeeds in avoiding those dopamine rushes. Still, I wondered if Below was precisely the game Piotrowski wanted it to be.

"I've never once made a game that ended up exactly what I wanted it to be. I always have a very hard time seeing anything other than the faults in any of the games I've worked on, especially immediately after launch. I'd imagine that most game makers feel this way to a point," he said. "Below was a long and very difficult project, so I think it'll take me awhile to see it with fresh enough eyes again. Right now, I'm still so close to it that all I can see is the cracks." Though, he says, many of those cracks have been filled by post-launch work on balancing and patches.

I'm immensely grateful that games like this exist - games which offer less in the way of gratification and instead tickle my imagination. Other people may not have taken to it, but maybe in a decade it will garner a following who appreciate its opacity and weird friction in retrospect. Piotrowski is certainly interested in playing their game ten years from now.

"I'll probably think it's pretty cool."