A Web Of Lies: Democracy 3 Hands-On

Breaking Britain

Damn you, Democracy 3, and damn you Cliffski. I wouldn’t say I’m quite at the point where I sympathise with the many blood-sucking insects that make up the UK’s political scene, but I worry that I’m starting to think like one of them. When I began playing, I was determined to do the right thing. A couple of hours later, I realised I didn't know what the right thing was anymore. Two days in, I'd have chopped off my own hand for a few more votes.

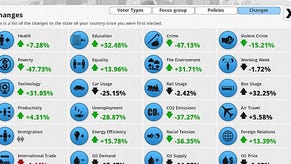

I’m trying to steer the country away from economic disaster, having spent my first year in office encouraging higher standards of science education, attempting to prevent the British from becoming the brainless backwater of the 21st Century. The plan was working and the people (most of them; some of them) were happy, but the expense of funding the future threatened to punish the present. Budget cuts loomed and I swiftly found myself between the rock of populist appeal and the hard place of economic necessities. Idealism dies young in Democracy 3’s high-pressured simulation, where every choice makes somebody unhappy and the main screen, a political petri dish of interlinked nodes, soon comes to resemble a nefarious web.

Over the last few days, as I’ve tinkered with Positech’s latest government sim, the sense that those nodes – and the situation they represent – were acting as a trap became embedded in my brain. I, the Prime Minister, am a fly, caught on sticky strands that I can tug one way or the other, but can never escape. Admittedly, I can fail, fall short when the election rolls around, vacating my place on the chopping block and leaving some other poor bastard stricken and splayed, dangling like a piñata in full view, pummelled by polls and impossible choices.

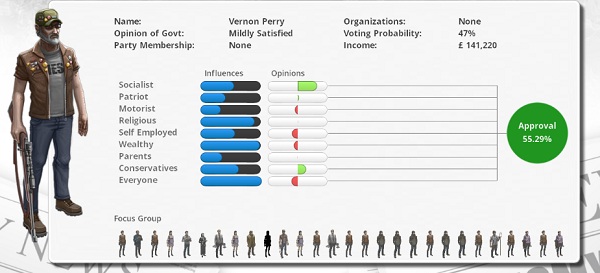

Democracy 3 never lies to the player, which is extraordinary considering its themes. Or perhaps it pulls the wool over my eyes constantly but is incredibly good at concealing the fact of its fictions. That seems unlikely. The mathematical models that drive the consequences of every decision, major or minor, are transparent. Hover the cursor over any policy decision, population segment or funding slider, and lines appear showing which other aspects of the system will be impacted.

It’s the kind of insight that even the Challenger 2 of thinktanks would fail to provide. Taking tourism as an example, we can see that a high sales tax, terrifying levels of violent crime and border controls that would shame Arstotzka are all putting a dent in the potential earnings from visitors to my increasingly Orwellian Britain. This leads to serious problems. Ninety percent of automobile accidents are caused by impact with unsold novelty replicas of Tower Bridge and with Britain beating seven shades out of itself while tourists stay away, there’s a real danger that the next royal baby will be born without a single camera lubriciously angled to appreciate its arrival.

I’m tempted to close the borders completely, to let the island nation sever its links with the world and fend for itself. I’m extremely popular with the kind of patriotic loons who holler and applaud every time I loosened gun laws (there are currently no restrictions whatsoever on purchase or ownership) and tightened immigration laws. I won’t earn re-election for an extra term, having driven most of the country to despair, but could things have been much worse?

To explain precisely how things could have been worse, I’d like to talk about my efforts to do right by the people of the United Kingdom. My version of ‘doing right’ involves the creation of a tolerant society that helps those in need but also rewards brilliance. I also quite like the idea of Big Government, especially when I am the government. I’m mega-ego-maniacal and wouldn’t have taken the job if I didn’t think I could improve every single aspect of the country, from spy agencies to healthcare, by taking on the yoke of leadership and flourishing under the strain.

It’s not a yoke though, remember. It’s a web. The stresses and pressures of leadership are not relentless and crushing. There are no time limits, no real limitations at all apart from political capital, which is the currency required to take actions, generated by loyal cabinet members between turns. Instead, the difficulty comes from the realisation that pulling any one strand causes an unwanted effect elsewhere. I don’t think I’ve made a single action that hasn’t had at least one undesirable consequence. That the game explicitly details those consequences beforehand makes the decision-making all the more difficult. You’re pulling the trigger knowing full well that it’s pointing at somebody’s head.

And so it goes. I’m caught between the need for political survival, which requires me to offer pity-fuck policies to unhappy demographics, and the desire to create a decent society, which requires me to stop using phrases like ‘pity-fuck policies’.

In order to ensure I’m elected for another term, I spend the first term pandering to the masses. I lower taxes, and improve spending on education and health. In order to balance the books, a sharp increase in corporate, property and inheritance tax.

Obviously, anyone who owns property or inherits anything at all must have plenty to spare. Or not, as the case may be. Suddenly, I’m unpopular with old people, particularly the ones surviving on pensions in large houses they can’t afford to maintain. I’ll need to find the money that goes toward building my utopia elsewhere. Becoming an instant caricature, I cut police and security funding. When everybody takes to dancing in circles with flowers in their hair, we won’t need a police force.

Britain’s proud ship of state sails onward. For a while.

Toward the end of my second term, no matter how many sliders I adjust and how much I try to fix things, it’s all gone a bit Clockwork Orange. I’m very unlikely to win re-election again and the security tab shows that there are several increasingly dangerous organisations on the rise. Even though I was intentionally pushing my decisions to extremes, I can’t help but think this is the world I would have unintentionally created given enough time.

Reading Alec’s experiences, I suspect we’ll both find that balance is the key. Stable, middle ground, run of the mill governing. The game’s strength is in presenting so many options, all of them enticing and, importantly, all possible from the beginning. There are limits on power but despite its sober appearance, Democracy permits flights of fancy and I suspect a lot of the pleasure I take from the finished version will be found in pushing the simulation as far as possible in various directions.

It’d be interesting to begin with a manifesto, or even to spend the early part of the game in opposition, attempting to topple a current government by over-promising and gleefully celebrating when they plunge the country into chaos and debt. The most devious aspect of the game is the rapidity of the indoctrination process. I’d been playing for about half an hour when I found myself convinced that I wanted to win the next election in order to be a better leader in my net term. Compromising today in order to be an honest man tomorrow.

Until tomorrow comes.