Wot I Think: Ashen

What's the scoria?

If you’re summoning Dark Souls, you have to be prepared to make a deal with the Capra Demon. In this pact, you will be granted the power of From Software’s ideas, yes, but you will also be doomed to comparison. You’ll only be seen in the light of that which came before. Ashen has made such a pact, and it invites that comparison especially often. It sticks so closely to the Souls formula it could be a dream Hidetaka Miyazaki once had. But lapsed hollows who look closely will also find that it uses the template to create its own mythology and its own admirable spirit, one of restoration rather than decay. If Dark Souls is a tale of perpetual, cyclical death and redeath, Ashen feels like tramping through a creation myth as it’s still being told. I like it a lot.

You play as a chump who has just stumbled out of cave. An ancient being (the Ashen) has exploded and brought light into a world that was once black as your boot. You and a few NPC pals soon found a village and are tasked with protecting the light-bringing deity that shines over you.

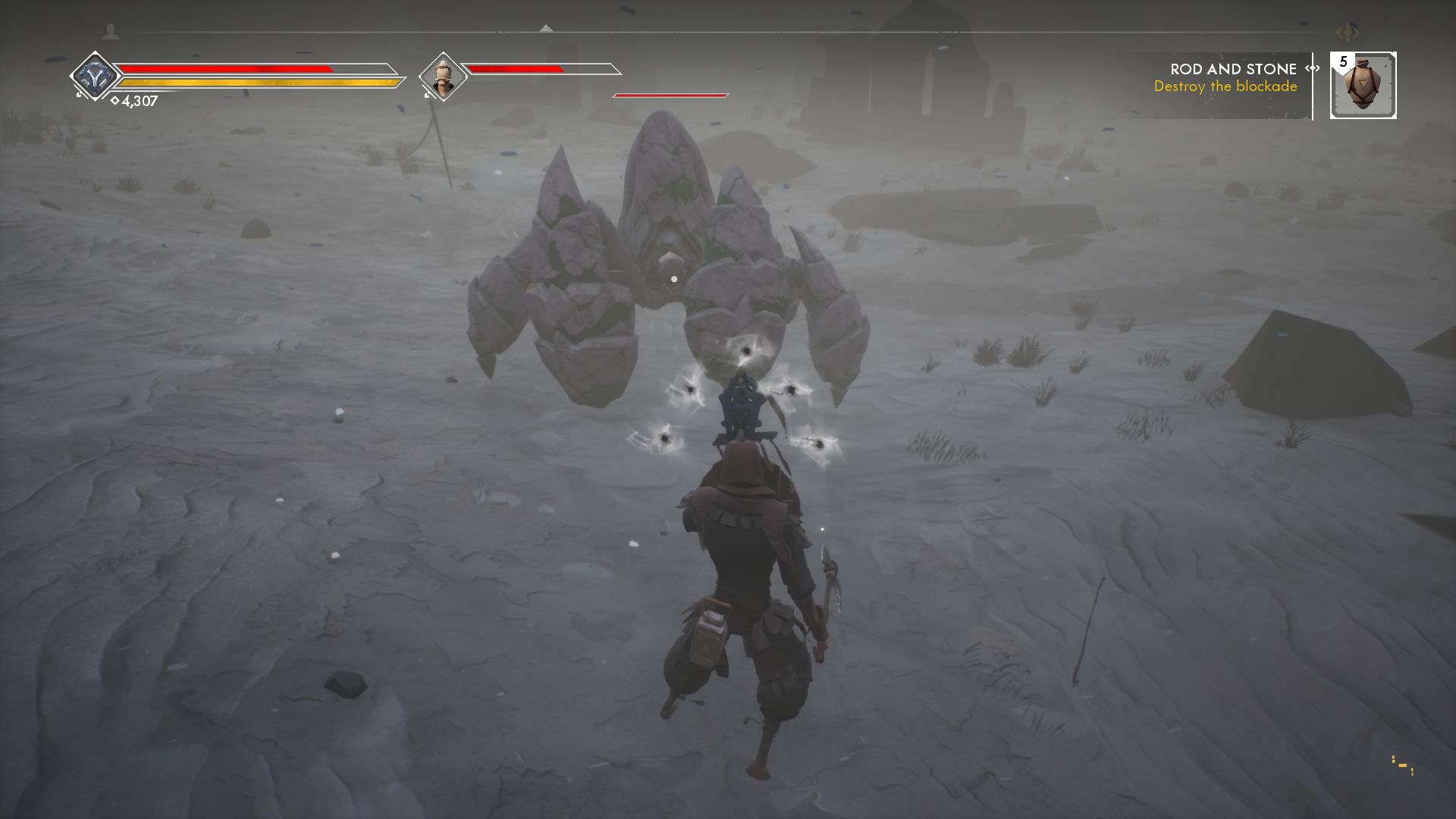

Much of it involves sallying forth, while bashing and slicing the geezers and monsters who storm at you across the grass and stone of this open land. The controls are so tightly bound to Soulsian principles, the movement so similar in its weightiness and deliberation, that veterans of Lordran will be dashing down its streams and locking onto enemies with barely a need to acknowledge the short tutorial. I’m using a controller, and the differences are so few, you can count them on one knuckle: climb ledges with ‘Y’.

There are other differences, mostly superficial. Instead of bows or crossbows, your ranged weapon is a pack of spears. Instead of a torch, you have a lantern. Your health-giving Estus flask is a gourd. I like this last substitute, because it makes me imagine my axe-wielding character as some kind of warlike Argentinian slugging yerba mate in the middle of a fight.

You still lose all your “Scoria” if you die (that’s this game’s stand-in for Souls) and you can still retrieve your bag of Scoria by going back to the scene of that death. Other fundamentals are sightly different. You increase your health and stamina bars by completing quests, instead of “leveling up” anywhere. And your Scoria-dollars go towards improving weapons, or buying upgrades for a talisman. These trinkets give you different bonuses. I’ve got one that makes my sprint cost less stamina, so I can cheese it through hound-infested valleys like some kind of Usain Bolt of ancient folklore. Another upgrade gives you more health the further you go from home, one of the game’s many nods to the safety of its bright village.

Let’s get one thing out of the way early, for all ye preoccupied with your own crumbling mortality: yes, it is easier than its inspirations. At least, it feels much gentler to this clumsy chosen undead. I don’t simply mean “you can kill skeletons quicker”. It’s a softer adventure in general, not only as a traipse into some outlandish fantasy kingdom but as, well, a videogame.

I mean it has game stuff. It has a map, it has waypoints and quest logs and a compass and jolly AI companions who potter along behind you should no human player become manifest (more on the multiplayer later). It has little glowing icons above stuff you can touch or use. It has great big beams of light coming out of the waystones that serve as checkpoints, so you can see exactly where you have to go next. Your map is unveiled in sections, and shows big tracts of land each time.

When you look at this map, the naming conventions are pure From Software. You can tell the designers had fun coming up with names for these hovels and shorelines. Look, there’s the Whispers, and over here: the Seat of the Matriarch. There is the Gullet, Sindre’s View, Tower of Gnomon. No, don’t go to Solitude, that’s where the man who likes to smash ribcages lives.

Some will doubtless look at this map and it’s questy waypoints and see interlopers, hateful beacons that shine so bright they only rob the Soulslike of its mystery and discovery. Others will see them as a helping hand, the much longed-for voice of direction that these games have been missing for so long. I’m not sure where I stand. It would be ignorant and reductive to call Ashen “Lite Souls” but it is maybe a “Lighter Souls”.

I mean that both in its fighty moments and its reflective ones. As you travel down the “King’s road” of the map, you complete quests for your fellow villagers. This always brings you back to that hometown, Vagrant’s Rest. With each passing quest you’ll see the village grow. You depart, leaving a pipe-smoking chap called Jokell standing outside his half-built home, and return an hour later with his dad’s notebook, only to find Jokell’s house is fully built, and has a little windmill on top. This is what I mean when I say it feels like a game about restoration. RPGs are usually happy to start you off in your childhood village.

Here, you get to watch it being built.

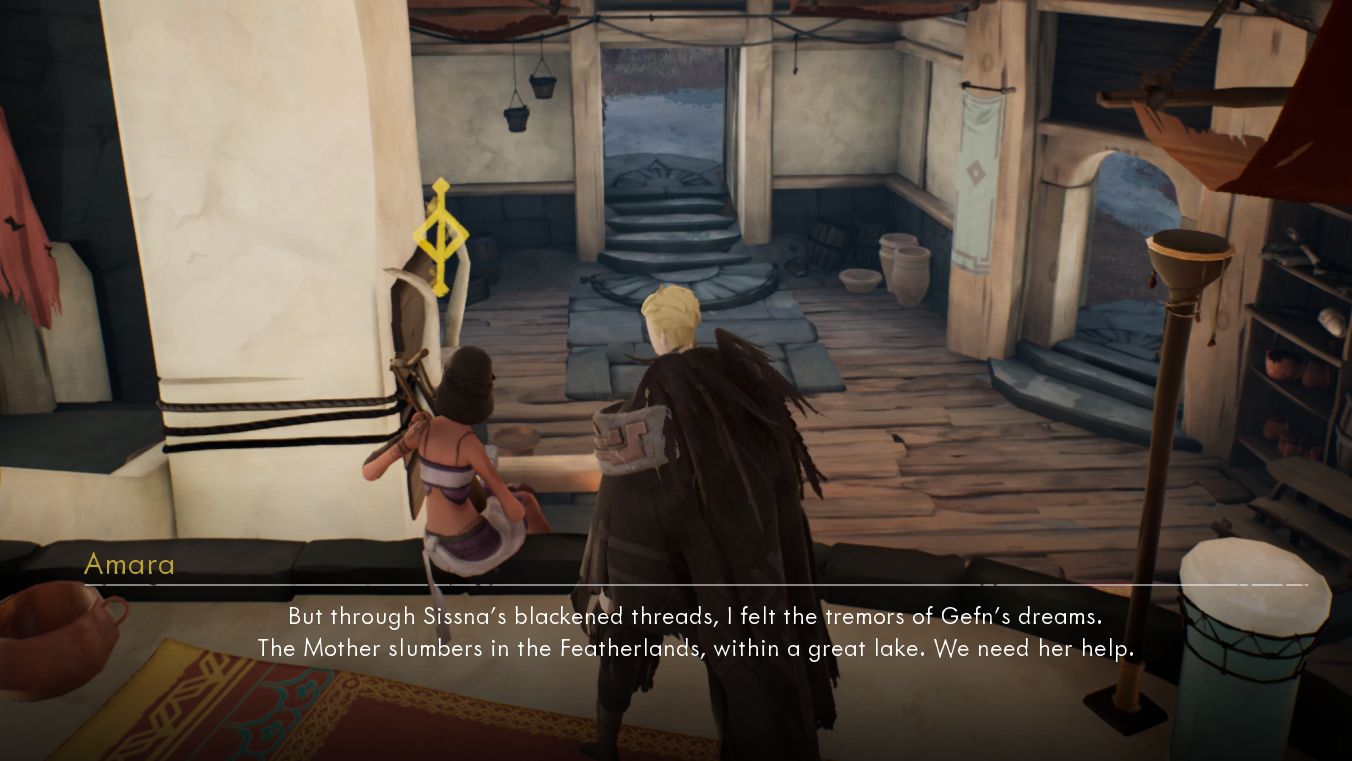

Sadly, not many of the characters in your village are particularly flamboyant or interesting people. The naturalistic tone set by the rocky landscapes and oasis-like settlement isn’t matched by the dialogue, which is as dry as puff pastry, despite being strewn with fantastical colloquialisms. “Find granny Nella,” says one character, “she knows the knows.” And later: “Well I’ll be a new-hatched scaglet.” These slang phrases are a good effort, but given that I don’t know what a “scag” is, never mind a “scaglet”, they don’t offer much relief from the lore chores.

In this it shares Dark Souls' own storytelling flaw. It’s all exposition, survival tips and name-dropping. People you don’t really know nor care about. In quests, you’re often asked to seek out an Ake or a Fiske or a Nella or an Aho and left with the impression that you must care about this person only because your fellow villager has exhibited some basic emotion about them. Aho is Jokell’s brother. Ake betrayed the tribe of Eila. But if I haven’t been given time or reason to like my villagemates, it’s unlikely I’ll care about their relatives or their enemies. It’s especially disappointing to be given a “hunt three wolves” quest early in the story.

But then I leave the pleasant streams of home and go exploring again, through the caverns infested with shadow people, the ruins populated with slavish miners, or clifftops peopled with giants. I go out into this colour-drained world and remember why I love this kind of adventurous deathtrap game. Because it’s about the land more than people. It's about slow, methodical exploration, your journey across causeways and through rickety fishing villages long abandoned by anyone not wielding a club. There are moments during these jaunts that make me blurt aloud: “whoa!” or “agh!” or “cooool.” And although I can liken many of these more cinematic reveals to other games, like Zelda: Breath of the Wild or Shadow of the Colossus, there’s a sense that, yes, this wonderous being belongs in this world too. This creation myth needs one of those.

After maybe 20-25 hours, I’m on what feels like the final boss (there’s still a part of the map I haven’t uncovered, but I can’t tell if it comes after this boss or is a semi-secret area I’ve missed). I’ve unlocked the ability to fast travel between waystones, and this is a particular spittoon I like to gob at, because fast travel is the killer of deliberately intricate geography. There are many shortcuts and secret routes here, but few have the same “aha!” quality that explorers of Lordran have come to love. I am going to let this go, however, because at least I had to work a bit to unlock the fast travel, something even Souls games have abolished in an effort to appease impatient players.

At one point, you also get a power that lets you throw magic teleporty spears at glowing statues that litter the hillsides and gulches. You turn into a shadow and zap straight to the statue you hit. I worried that this would further kill some of that slow, deliberate dandering that I like, but really it just means I can reach the top of that weird pillar over there, or that isolated rock out at sea. It’s a nifty little superpower that makes you want to go back to old plains and mountainsides to see what you’ve missed.

There is a more mundane problem than the inclusion of [spits] fast travel. And that is a basic roughness. There’s sometimes a slight jank to the combat. Enemies lunge at you with erratic intelligence and agility. Sometimes giant bruisers are capable of leaping for 20 metres and crushing you into the ground, sometimes they’re incapable of moving because an ankle-high ledge is confusing them. The rules behind when and where these enemies respawn is likewise erratic. I’ve had moments when lumbering club dudes have respawned behind me, only a minute after having killed them, leaving me surrounded on a narrow cliff edge, too frightened to dodge, too exhausted to block.

I’ve also had some bugs. Cross-legged warriors slicing at me with invisible strikes. Enemy spears passing right through solid walls. And a couple of frustrating fatal error crashes in the middle of that maybe-final boss. These bugs aren’t so common that they’ve ruined the grand vistas or the tension of the tomb raiding. But they are most noticeable when you’ve got a fellow human beside you, bashing skulls and throttling bandwidth.

Finally, I’ve gotten to the gristle. The multiplayer is a Journey-ised version of Souls matchmaking (Absolver is another touchstone, in more ways than one). The trick here is that the game matches you with a nameless player and makes them appear as one of your fellow villagers: a beardy blacksmith or an unnaturally tall, blue-skinned brewer. In your pal’s game, you’ll also appear as an NPC. In times when no player can be found, you get an AI companion who will vanish as soon as a fellow player does turn up. This means that sometimes your AI mate will disappear at a crucial moment, replaced by a player icon on your compass. At which point you start spamming the “call” button to cry out to your human partner, unable to see them among the twisted boardwalks of a canyon slum or the dusty air of a swamp.

I’ve had some stinking co-bludgeoners. Players who run ahead, slicing everything and not even bothering to stop and appreciate the scenery. But I’ve also had some excellent playmates. Folks who have slowed right down to match my sluggish pace, equally keen to find every trinket and explore each stoney nook. One player guided me to the top of a ruin, hopping between tiny footholds that probably weren’t even designed to hold the player. Ashen’s eagerness to let you climb sometimes results in the kind of stupid platforming that gives survivors of Blighttown the trauma sweats. But it also means that this player and I had an excellent time leaping from one outcropping to another as we scaled a crumbling fortress. When we neared the top, I fell to my death. I wonder if they felt sad about this, or just laughed at my terrible balance.

Anyway, you can turn the multiplayer off if you hate people. But so much happiness comes from meeting a fellow slowpoke, that I only resorted to this option when my playmate refused to join me as I approached one of the “two player only” dungeons. These are scary areas, with big bosses at the end. You can unlock a talisman upgrade that lets you open these dungeons and go in alone, but why face a giantess by yourself when you can fight her with a human-possessed Jokell?

Despite the limits of this multiplayer, I’m happy enough to be Journey-ed up with other players, rather than fiddling about with soapstones and summonings (you can still password match to a specific person, if you want to play with your mate James). A lack of emotes means that I welcome my fellow explorers by jumping up and down on the spot a couple of times, or press the “put down lantern” button over and over, resulting in a kind of spasmodic glowstick dance which I hope they understand as a “hello”. It’s sad to lose a helpful mucker who’s been clobbering shadowfolk alongside you, when they finally decide to pack it in and head back to the village to bank their Scoria-bucks. But nothing was built to last. One day, James will forget about you too, you know.

As I prepare to go bumbling back through the glimmering palaces of the (maybe) final section, I know that the Capra Demon’s curse is still there. I must inevitably compare this to Dark Souls itself. And in doing that, Ashen has already come away poorer than it ought to. But if we think of it another way, maybe we can circumnavigate the curse. So let’s compare it to other Souls imitators. Because when I think of The Surge or Nioh or Hollow Knight, I’d rather be enjoying this gorgeous panorama of a game, climbing to the top of its mountains, lurking through its deep caves, or returning to my gentle hometown to see how it's grown while I’ve been away. In short, I’d rather be playing Ashen. A lighter souls, yes. But not a lesser one.