Premature Evaluation: Eternal Winter

Snow Joke

Each week Marsh Davies staggers off into the barren, frigid wilderness of Early Access and comes back with whatever stories and/or slabs of dog meat he can find. This week he sticks on his mitts and braces for subzero survival sim Eternal Winter.

There’s good and bad failure in games. Good failure teaches you something, whether about your own resolve and ingenuity or the world these things are tested against. Good failure is a dynamic, riveting generator of experience. Bad failure is, I fear, what the vast majority of indie survival sims have to offer: a way of capping off a game with no definite trajectory. Like wading into chest-high cement, you do eventually stop, but you wouldn’t call it much of a journey.

The prompt update cycle of Eternal Winter suggests it may soon offer the former kind of failure, but right now, so spartan is its world and the things one can do in it, that it’s in the latter camp. You find food, then you don’t, then you die. That it’s bleak and desolate is part of its setting, of course - a world of stretching snow, punctuated only by evergreen trunks and the husks of houses. But I’m increasingly of the opinion, having played many games like this in the last two years, that maybe this setting isn’t all that interesting a basis on which to build a game; that, in fact, survival games are basically Robotron, except instead of a swarm of enemies, you have emptiness, a chasm which slowly consumes your ability to continue; that failure is a failure to find interaction; that this failure is the game’s and not the player’s.

That’s not the case with all survival games - but those that excel are the ones that make survival a vigorous process of thought and action, and not simply a slow and futile effort to stop a number reaching zero. Eternal Winter, being so early in its design, has few opportunities to show you what it might become - and Valve’s new guidelines prohibit the developer from making such promises - but it has at least four things going for it. It has dogs.

These dogs pull your sled and have their own energy requirements that you must balance against your own. You won’t get far without them and you wouldn’t want to because they are adorable. I name mine after the most adorable kind of people I can think of: people who give me money. Botherer and Rossignol lead my team while Gonnas and Pip bring up the rear. There’s even a button to talk to them, because, as the tool tip points out, there’s no one else to talk to. It’s not clear if this has any psychological benefit, but Gonnas nonetheless gives an appreciative little howl - just like the real Gonnas does when you tickle him under the chin. Like I said, adorable.

But, alas, a man cannot survive on coochy-coo faces alone. I must hunt - and so I mount the sled and skid off into the white expanse before me. Perhaps a little later than it should, it dawns on me that I do not know the way back to the hut at which I started. I remember seeing a compass in my inventory, and I whip it out, having to dismount the sled first. Of course, I have no idea which direction I was facing when I set out, but a tool-tip does instruct me that I can mark my current location by pressing M. Because I’m an idiot and liable to immediately do anything I see in an on-screen prompt, I press M. This is foolish, as it’s more than likely that the compass was in fact already pointing back to base camp and now I’ve ensured I can only find my way back to a whole pile of snow. If I didn’t already know it, I know now: I would definitely die in the wild.

Luckily, I’m not too hungry or dehydrated yet, and I figure the original digs weren’t up to much anyway. My hounds drag me onwards, to a house with a large veranda and two snowbound cars out front. There’s a packet of crisps and a tin, but not much else. Houses are little more than shells here - a limit of their polygonal complexity rather than architectural choice - but it makes it relatively easy to loot them. There appear to be more, too, in the distance, dotted among the trees. A road, barely perceptible in the snow, snakes towards them, but, judging by the black shape that moves back and forth across it, the route is not unguarded. As my dogs close the distance it becomes clear that we are in pig country - and its boar-der officials are none too friendly.

Though we zip past at speed, the swine still manages to take a swipe at poor old Gonnas. Ever the brave warrior, he ploughs on, and soon the pig loses interest in pursuit. We’ll be back for your bacon, mate, I think. These murderous notions begin to crystallise into an actual plan about the time I discover a crossbow. The hunting lodge it’s in also has some supplies, a cooking stove, some sort of bin full of sticks that you can safely set alight, and a bed. In the build I play, sleeping is the only way to save, giving you a choice of two, four or eight hours of unconsciousness. It’s annoying, because I don’t really want to snooze the day away, but I do want the ability to quit without losing loads of progress. I take a power-nap and awake with a thirst for vengeance.

Porkchop gets a temporary reprieve, however - a fox has wandered near the hut. I stalk my prey, but without any evident stealth affordances, it’s not clear what stalking in this game constitutes. I fire off an arrow or two as the fox gambols away, but I can’t even see the arrow once it’s travelled a few feet, making it difficult to correct for its parabola - if it has one. An encounter with a stag goes similarly well. There’s no obvious way for me to get within a lethal range of these timid beasts. Luckily, other beasts are only too keen to close the gap. A wolf charges at my dogs, and I catch it with an arrow in its arse. It doesn’t even break step and bundles straight into my dog pack, snarling. Suicidally, it turns out, as my furry friends finish the job for me, though not without taking a few scratches themselves.

I quickly butcher the wolf - and another I entice into combat soon after - and head back to the hunting lodge, the location of which I presciently bookmarked. I’ve looted enough tins and nutrient bars for myself, but my dogs will only eat meat. Raw meat is less nutritious than cooked, says a tooltip, and I’ve managed to scavenge some matches for the stove and sizzle up a few steaks for them. Disaster strikes! The “feed cooked meat” button turns out to be inert - presumably a bug - and so I’ve essentially just denied my canine chums a meal after wasting many calories to locate it in the first place. I feed what little raw meat I have left to the two hungriest pups, and, feeling defeated, head to bed as the sky blackens.

This error snowballs. Two of my dogs are quickly near starvation, and their energy - a separate stat to hunger - is low. Too low to pull the sled for long periods of time, in fact. It’s not clear exactly which dog is responsible, however, and feeding a bottle of water to the dog with the least energy fills up the bar, but does not stop the problem. Periodically, the sled will just park itself and turf me out, declaring that one of my dogs is too tired. I think it’s Gonnas. I try talking to him but he just howls. Stupid adorable Gonnas.

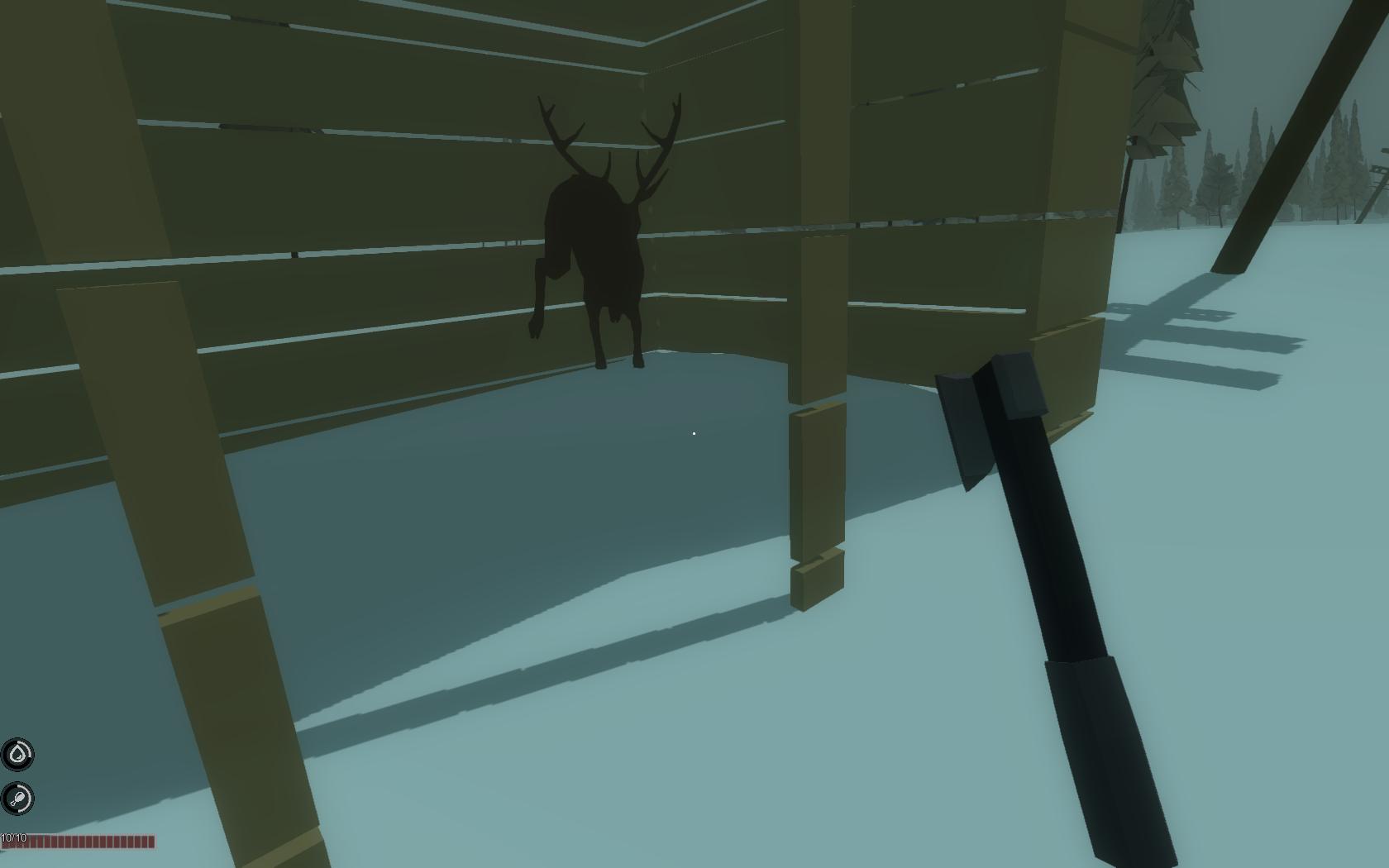

Maybe it’d help if he wasn’t starving? Clearly, I need to find more meat for the dogs. But I also need water myself and melting snow isn’t an option in the game. When my dog sled packs in again, in the middle of nowhere, I take off on foot, running for miles and miles after a fox, who only ever gets incrementally closer. Fortune smiles upon us both: the fox, making good on her reputation for cunning, leads me past a small shack. Within it is a stag, caught in a run-cycle against the far wall. I bury a hatchet in its butt until it obligingly turns into food.

It’s only by some miracle I find the abandoned dog sled again, as I didn’t have the forethought to bookmark it before pelting after the fox. The dogs, now even hungrier after my lengthy absence, happily guzzle down the raw flesh, while I eat one of the cooked steaks (which, weirdly, appears to have transformed into a large, smooth grey object, like a pebble). But, though my belly’s full, my mouth is very dry indeed. Nor has eating improved Gonnas’ energy levels. Realising that if I don’t keep the sled moving I am going to die, I make a decision and put an axe through the back of Gonnas’ adorable head. And then I feed him to his friends.

The sled is in motion again, but not for long. The dogs need another sit down as we approach the outskirts of a village. I scour it for supplies, but there are none to be had, and I’m on the very cusp of terminal dehydration. The dogs’ energy levels are also getting low. If I set off for another village on foot now, am I just condemning them to die in the cold tied to a sled? There’s not even a way to unleash them.

Well, there is one way.

I take out my axe. It’s slow work but my dogs oblige by standing still, whimpering as I hack into them.

A minute afterwards, as I’m stuffing their meat into my pockets, I wonder if that was really the most sensible thing to do. Five minutes afterwards, when I stumble into a hamlet that appears to have stockpiled the entire county’s supply of soda cans and water bottles, I realise that it definitely wasn’t.

I can’t quite bring myself to drink any of it, though. I will only be postponing the inevitable: without my sled, I will eventually scour every consumable within range, starve and die. Even with the sled, this would be true, granting me a few more days of bleakly allaying that voracious nothingness into which the game’s minimal interactions will eventually tumble. But what would be the use?

Actually, I can think of one use. I stagger on for a few more minutes until I see a familiar shape on the horizon. A wolf. I hope it appreciates my life more than I do.

I might have taken this route even earlier were it not for Eternal Winter’s canny effort to make me responsible for four other lives. Yet the only choice the game really gave me was when to end them. Necessity is the essence of the survival game: at its best, it forces the player to invent, to improvise, to weigh multiple strategies. One day, Eternal Winter may be able to articulate such varied responses - it is getting fairly substantial weekly updates - but not quite yet. Perhaps, currently, it’s actually a more honest representation of what survival would mean at the end of the world: you exist only to delay your non-existence. But you may reasonably wonder which is preferable.

Eternal Winter is available from Steam for £7/$10. I played the launch version available on 26/11/2014 - a later version (.105) addresses dog energy issues and allows for more save points. Read the update notes here.