Gaming Made Me #3, Kieron Gillengthily Played

Picking the handful of games that made me is somewhat tricky. Not picking the games that made me, but picking the handful. The house of my gaming past is on fire and I only get to grab what I can carry? That's not how I think.

One of the things I tend to chew over with games is their almost utilitarian nature - the idea that games (and art generally) is there for a purpose. Moreso: that pleasure and its various shades are a purpose. As such, depending what interested me at any given time, I could do an autobiography via games, talking about why I went where, when and what that said about games and what it said about me. Something like Garry Mulholland's lovely This Is Uncool.

So I'm narrowing it down a bit. Looking back, it interests me how many games were external things which changed everything. I spend most of my gaming time sitting inside this screen. But some of the most memorable games I found out there. I left home, went somewhere, met a game, and when I came back, I was a different person. An Adventure. There and back again...

So appropriately enough, we start with this. I've told this story before on podcasts, but it seems I never got around to doing so on the site. Could you humour me?

When I first remember hearing about gaming, the Hobbit loomed large. It was introduced to me by my best friend. He was the youngest brother of three. I was the oldest of two. As such, he was exposed to a mass of illicit information via the elder siblings: things which appeared to me as they'd been dropped from another, more exciting world: American Comics; The less Enid Blighton strain of choose your own adventure books; Eddie the Head, the Iron Maiden Mascot who prompted intense theological arguments.

Our Catholic education left us sure that God was more powerful than the Devil. However, it was equally true that the cover of Iron Maiden's NUMBER OF THE BEAST album proved Eddie the Head was more powerful than the Devil, because it pictured him using Satan as a marionette. So... who was strongest out of Eddie and God? It troubled us.

Anyway, relevantly, this same friend introduced me to computer games.

The idea of games in the home was alien. While not exactly technophobic, my parents always lagged behind the technological curve. My friend enlightened me about the joys I was missing, primarily on our weekly walks to the swimming pool. Every Wednesday, our school trudged the half mile to the local baths. There and back again, he told me about his latest adventures. "Oh yeah - I waited until sunrise, so the Trolls turned into stone..." "I can get in this barrel in the Elf King's cellar, but I can't work out a way to make them throw me in the water." "Yeah, I don't go that way any more... there's spiders up there." "Oh, I'm in the Goblin Dungeon, and there's a trapdoor in the basement." "Ah - I tricked the wizard and the dwarf into a cave and then locked them there."

I listened, mouth agape. This thing he spoke of was the greatest thing in the entire history of humanity.

Time passed and I finally had a chance to go to his house and see the game. I'd say months, but I suspect with a kid's perception of time, it was actually just a fortnight. It felt like eons. You can't imagine my excitement at sitting there as the spectrum sang its atonal loading noise song. Christmas-morning anticipation ran through me.

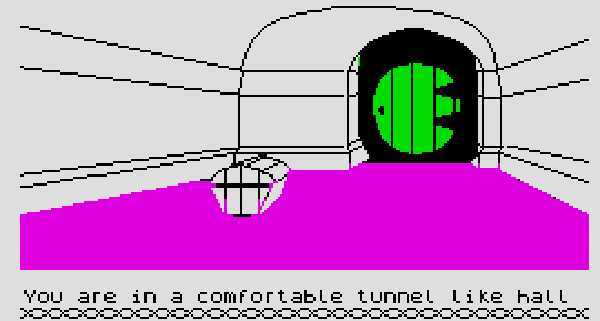

The game started. A hobbit-hole door appears on the screen, in lurid green.

I glance over at my friend: "YOU NEVER TOLD ME IT WAS JUST WORDS!"

That's how games and I got together and in that moment, there's the future echo of our relationship. That is, joyous awareness of their infinite possibility, depression at their stunted actualities.

But it was a start. I OPEN DOORed and was away.

Kung-fu Master (Data East)

I was in the arcades before Kung-fu Master, of course. I'd have been nine by the time it came out in 1984. The arcades were the only time I saw games - or in the working men's clubs, which was either a game of Scramble (in Cannock's sprawling club) or something Galaxians or Phoenix shaped (the GPO around the corner). I dug them a lot. If you wanted an Us and Them moment, it'd be when a kid asked me why I was playing the game, as no money ever came out (as opposed the to the fruit machines). I was dumbfounded: pleasure comes out.

Kung-fu master was different, because it was a game I saw a lot. Being in various places, it was the introduction to the idea of games following me around. The idea that a game could be a shared social language - and bond - between complete strangers in different places. It was a shared social experience, despite being single player.

It also had awesome flying-kicks.

The small things appealed. The incredible precision of its control system. A button press and a whiplash kick with none of the slowness of most games. The size and clarity of the graphics. The plot. It seemed far more like a real place - more immersive - than anything I'd played before. I'd realised that visual representation alone wasn't enough when I burnt through 50p coins with Dragon's Lair the year before. It was the right kind of visual representation. It was a game which made me jump around the room like an idiot. Pac-man or the space-ship games didn't make me do that. They made me go pschu! psuchu! laser noises, at best.

It had awesome flying kicks. And those multiple punches to the face. And knives. And splashes of red and mobs of men, falling to their deaths.

The brutality, I realised, helped and appealed. Gaming as transgression. My parents were right to be worried.

A year later and a family holiday. Still no home computer.

To a Butlins holiday camp, or some local knock-off of Butlins. People in coloured jackets. Singing. Chalets. And the best arcade I'd ever seen in my life, with prices lower than anywhere else ever. My brother and I devoured them all, but we paid almost a religious admiration to the hefty, brand-new four-player cabinet that towered like a monolith from a utopian future with excellent waterslides.

It's easy to forget how innovative Gauntlet was. The four players. The role-playing elements, taking what was still subcultural and integrating it on the main stage of pop-culture. The use of dialogue. "Warrior needs food badly" lives on as a great thing to say whenever you're hungry. Fast-forward to years later when as a student we're playing Gauntlet 2, and kill a Dragon to be greeted with the phrase "I have never seen such bravery!". Yelps from semi-grown men. Gauntlet said something new. For months we were uttering the phrase whenever anyone did the most innocuous thing. Empty the bin? Go out in the rain? Go off to dump an unfortunate ladyfriend? "I have never seen such bravery". Ah, students. Always happy to give people reasons to hate us.

Even its exploitative elements - feeding the slot coins to get more health - Gauntlet screamed the new.

On the last day of our holiday, we talked our parents into playing. All four of us, against the dungeon. Dad silent and concentrating. Mum Giggling. I don't remember much about the game, except how wonderful it was to have my parents along for this journey and how I wish it could happen more often. Games are for everyone. Fast-forward over twenty years to last year when my parents were visiting: Rock Band arrived, and my dad was the first person to hammer out on the drums.

It was only when writing this and doing the maths that I drew a line between this summer holiday and the Christmas, when we received a home computer. Or, at least, a Commodore 16, which was close enough to a computer. While I suspect they may have caved anyway, I can't help but think the communal experience with Gauntlet helped things along.

Move forward another couple of years, to another version of Gauntlet. We'd had a Spectrum+2 by this point, and my brother and I played the 2-player home version of the game for hours. It was a tape multi-load, requiring you to load another bit every eight levels or so. With infinite credits, by carefully planning our deaths, we were able to march on to see what lay ahead. Eventually, one day, we reached the end of the tape. There was no final level. We rewound and started again, barely blinking.

Another lesson: gaming doesn't end. It goes on. Winning doesn't matter. The journey is the point; games are experiences. Games are not just games.

Transformers 2005 MUSH (PennMUSH codebase)

Okay, this is something different.

The heart of my teenage years belonged to the Amiga and homes. My home. Friends' homes. I had friends who loved games and we travelled from home to home to play them. Immortal games. Speedballrainbowislandslemmingssensiblesoccersyndicategravitypower2chaosenginelegendsofvalourcivw

ormsonlywhendrunkharlequinanotherworldstardustliberationpopulouswizkidmonkeyislanddynablaster... oh, games. The Spectrum lived on. As far as my second year of university it was being used as a one-game console for playing Chaos when people crashed out in the early morning, machine passed around the room like - and often alongside - a spliff.

As part of my degree, I'd found myself in a placement year in an American lab in Denver. Random chance. And then I was gaming from home again for the first time since childhood.

At the time, I said I didn't game. Hindsight proves my definitions were wrong. This was after the death of Amiga Power, which provided my first work. Broke and a little burnt out, I skipped the whole period of '96-'97 games. It's an odd hole in my personal gaming history with regards to the mainstream - when Edge was hailing Mario 64, I'd headed a completely different way. In fact, I headed about as far as it's possible to go. I only prodded it at in a shop before returning to mope in my flat.

I had a pretty shit time in America.

It wasn't particularly anyone's fault. I realised swiftly that due to laziness and extreme distractability labwork really wasn't for me, and so treated every day at the job like a prison sentence, up to and including marking time's passing with lines on my wall. The people I was working with were lovely, but at least a decade older than me, and with families. As such, I was stuck, without a car, on my own, a long way from any place I'd want to go, and was bored to the point of insensibility. It was seven months into the ten before I'd managed to locate my sort of people to have fun trouble with, by which point - and looking back at the sort of ill-advised adventures we went on - I suspect I was more than a little bit mental.

It was also the year when I went native on the internet. I ran a website, lived on mailing list, and discovered MUSHes.

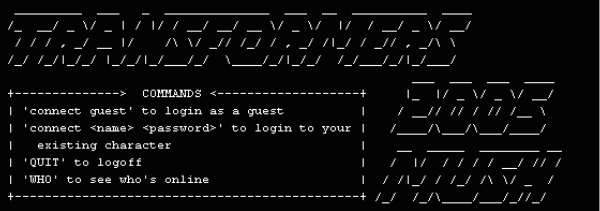

You'll probably be aware of MUDs, the text-based Multi-User Dungeons which were the first to explore the place the modern MMOs colonised. MUSHes - Multi User Shared Hallucinations - were, if the acronym didn't give it away, the poncier side of it. Imagine a role-play server where 98% of the time you were going hey-nonny-no! in the chatroom. They were nothing but the proverbial glorified chatroom.

On the other hand, they were glorious chatrooms.

At the beginning of the trip, I had no idea they existed. I knew about MUDs. I also knew how much they could devour your life, from the all-night sessions some of my housemates had at the university labs. That didn't sound that interesting to me. That sounded like doing the same repetitive things for hours. Surely that wouldn't catch on? As history proves, I was totally right on one observation, and totally wrong on the other.

I discovered Transformers 2005 MUSH by running through the corridors of the internet, seeing with amazement that there appeared to be enormous functioning community of fans for anything on there. This was, I stress, 1997 and we were amazed by such things back then. I didn't count myself as a Transformers fan. I liked the toys as a kid. I read the (superior) British comics back then. I hadn't really paid much attention to them for over a decade. The idea of an ongoing free-form roleplaying game set in the universe, just after the end of the films... it intrigued me. I had an idea for a character, applied, and soon I was playing. For hours a day. To the point where I ended up in serious trouble with my lab supervisor.

MUSHes are roleplaying games, but they're primarily plotless. Proper events - TinyPlots - are planned, which people can come and join in with - but much is based around players just hanging around and improvising scenes in character. Instructions are posed, with it entirely up to you to describe what your character does in either curt sentences or enormous florid passages of purest spam. Tf2k5 had a relatively complicated combat system with a load of statistics, but later MUSHes I joined - with themes not based around enormous warring robots - operated off little more than a +roll command to decide who would win when no consensus could be reached. Improvised roleplay with vestigial gaming. Performance art a sentence at a time.

I'd be interested to know how many people reading this played any MUSHes. It's something that few actually talk about. The closest to a games journalist exploring it is Leigh Alexander's regular riffs on her time playing Yahoo-Chat Final Fantasy roleplay, which isn't quite the same thing - MUSHes have maps, places to build, things to interact with. I'm comfortable calling them a game and keeping them in the same part of my head as the Hobbit.

When I got back to England, I continued to play in a more casual fashion. Well, relatively casual. With the pay-for-dial-up of the time I built an enormous phone-bill despite that. But the real work was done, in terms of what it taught me about gaming. It was a social game which provided me, in my lowest year, a social life and drama-aplenty. It left me with the ability to type at my normal ludicrous speed and honed my ability to pull ludicrous metaphors and turns of phrase from the ether - it was a real part of how the year of isolation turned me from an adept StuCampell/JNash/TaylorParkes/NeilKulkarni copyist into something approaching someone with their own style. And those hours gave my first experience with RSI, which haunted me down the years.

Games can sustain you. Games can improve you. Games can destroy you.

Thief: The Dark Project (Looking Glass)

Next time I left home to play games, the mood was more triumphal. After the experiences in the sciences, I knew my degree was useless. So I did the bare minimum of work and concentrated on writing. Somehow - the old stat about 1 in 10 people leaving university claiming they were looking for work in the media, and there only being jobs for 1 in 100, nagged at me while I worked bars in those months after graduation - I got a job. PC Gamer hired me as a staff writer. I was to work in a room with a mass of relatively young, booze-hungry men, and one woman whose job was to scare us all into doing some work occasionally.

And I was, apparently, going to review some games.

Thief wasn't the first game I reviewed (The Chaos Engine was, back in my home town, just to see what it felt like). It wasn't the first game I'd reviewed professionally (UFO on the A500 for Amiga Power). It wasn't the sample review I sent with my CV (The Curse of Monkey Island). It wasn't the first game I'd reviewed in the office (which was some racing game which I had to play briefly and write a 300 word review for in half an hour as part of the interview process). It wasn't even the first game I reviewed as a staff writer (which was a 280 word micro-review of a rendered adventure which I can remember nothing of bar I kicked it to death). But since that was delayed until the following issue, my debut as a writer for PC Gamer in the magazine was Looking Glass's magnum opus.

It seems miraculous to me now. It's like if Lester Bangs' first assignment was to go and interview the Velvet Underground. Within the first week on the job, I'd found my Lou Reed.

Of course, yeah, I know. Egotistical on all sorts of levels. But I was nothing but ego back then, with a tower of McCain Oven Chips bags wobbling on each shoulder, and everything to prove. The only thing was that I didn't realise how important it was. I lacked context. I was new to the world of PCs, only having owned one for a few months previously - never being rich enough to own such a thing before. The Ultima Underworlds, System Shock; these were games I knew by reputation, and little else. I was coming to the world's premier stealth game clean. And I could see all the parts of it mesh together. I could see how elegant its stealth-mechanism was, so obviously better than the digital fakery of Metal Gear Solid (Thief was Defender to MGS's Pac-Man). Most importantly, I could see the ghosts of all those other games of the past: I was shouting incredulously at the Hobbit, because in my head, it looked like Thief. This was it. This is how games should be.

Almost gave it a mark in the seventies, of course. The Bonehoard almost made me give up. I persisted and ended up giving it ninety. Which sound kinda mean, until you remember I was a AP veteran and true believer. As such, I'd never given a ninety before in my life.

The lesson, however, comes about a year later when I find myself in drunken conversation with a Looking Glass veteran who's over to show off Thief 2. I mumble an opinion that I tended to think of them as this sort of progressive, intelligent developer. I mean, in 60s rock terms, kind of the Velvet Underground.

She doesn't blink: "Oh, yeah. Totally".

The lesson being: people believe in games as much as you do.

The lesson being: you're not an idiot to think that.

The lesson being: you're not an idiot to think.

Thief, in a real way, justified my entire approach to the medium. So, if you're ever looking for something to blame, blame it.

Alternatively, the friend who showed me the Hobbit. If he only made me play football, you could have all been spared.