How small game makers found their community with Bitsy

A tiny tool for making tiny games

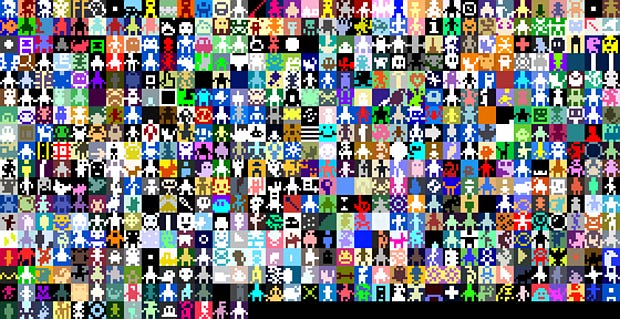

A year ago Bitsy released on itch.io - a humble game making tool described by its creator as a "little editor for little games or worlds". Since its release, more than 600 games have been made using the tool by 300 different authors.

On the surface Bitsy is an unassuming engine. It lets you create small pixel-art rooms that players can explore by interacting with the people and objects within them. Its simplicity hides a surprising depth, one that has drawn in a community of game makers.

“Bitsy came from my own frustrations with trying to finish a game,” says Adam Le Doux, Bitsy’s creator. “Naturally, the solution was to build a new game engine from scratch! I wanted to stop worrying about programming details, screen resolutions, platform differences, post-processing effects. I wanted to be able to immediately work on the heart of what I was trying to create: a world with a story.”

He was inspired by his favourite spaces in games - towns in 2D RPGs like Zelda, Pokemon and Final Fantasy, and walking simulators like Gone Home. “I've always loved walking around and talking to everyone to learn about their personal problems or the history of the town. Games like that gave me confidence that those ingredients - a place and its inhabitants - were enough to make something interesting.”

He created Bitsy as a simple engine that doesn’t require coding knowledge to create something within it. It’s an engine built on constraint, restricting you to 8x8 pixel tiles and a three colour palette.

“I made my first game about coming home to my apartment after work and finding my wife, Mary-Margaret, already napping on the couch and our cat begging for a snack,” says Adam. It used an early version of Bitsy, which required everything to be typed into a text file that was then loaded into the engine.

Adam created the web app version of the editor when Mary-Margaret and a few friends said they wanted to make their own games using it. He put it online, posted it on Twitter and figured that would be the end of it.

“Normally, tweeting about a side project is like shouting into the void.”

Bitsy took off. Game makers found that the editor's simplicity meant that they could make compelling games over a couple of evenings. The lowered stakes meant it was perfect for testing out ideas, making short mood pieces or expressing personal stories.

Claire Morley was one of these designers. She was drawn in by Bitsy’s distinctive art style, created as a byproduct of the engines constraints.

“I played a few other games from the Bitsy Moth Jam,” she says. “I loved how they all felt really similar, yet so distinct from each other. They all felt mysterious, but personal. They almost feel like they're all from an alien or ancient culture, connected together, and by playing them I was scratching the surface of something magical.”

Claire decided she wanted to make her own game. She made Cat’s Out of the Bag! for the next jam, a game about sneaking around a highschool and listening to people’s conversations. She’s since made a handful of Bitsy games featuring train journeys, snowblindness and a message in a bottle.

“Bitsy strips away anything that's not completely necessary to making an interactive story. It's a very focused and limited tool, but those limitations mean you don’t have all this noise about what art style to use or how to set up controls,” says Claire. “While those are important things, the absence of them means that it's easier to get to the core of the story, experience or message you're trying to convey. It's why Bitsy games often feel so conceptually strong.”

Bitsy games feel like they belong to a distinct form of game making, one with its own rules and visual language. Making a game in Bitsy feels equivalent to deciding to record a film using Super 8 or shooting photos with an analogue camera. While it’s easy to learn for beginners, there’s still lots of space for experienced creators to experiment with. It’s led to people doing things with Bitsy that even Adam hadn’t anticipated.

“People keep pushing against the constraints to invent new ways to use Bitsy that I never intended,” says Adam. People have made short films, procedurally generated radio tuners and astronomy simulators using Bitsy. Much of this inventiveness has been driven by the community that has formed around the tool.

“If development of Bitsy itself froze today, I think we could still spend years finding interesting ways to use it,” says game and tool maker Mark Wonnacott, who is passionate about the community that has formed around the engine.

“People are actually using it and playing each others games,” they explain. “There’s a good community of people helping and encouraging each other. People have drawn parallels between Bitsy and Twine, but I’m not sure if they’re thinking about the tool as much as the shape of the scene forming round it.”

Both Claire and Mark are at the heart of that scene. Claire has been pivotal in creating spaces for the community to flourish. Alongside Lorenzo Pilia (programme manager for A Maze and part of the Global Game Jam executive committee) she set up @bitsypcs, a Twitter account that shares news about Bitsy and games made in the engine.

The Twitter account led to the pair setting up a Discord, Bitsy Talk, which has become an unofficial home of the community. It’s a welcoming space where people can go and “share ideas, games and add-on tools”. There you can find people who’ve made half a dozen games giving tips to complete beginners.

Mark has become something of a Bitsy archivist. They created the Bitsy Omnibus, a catalogue of every Bitsy game. It was originally motivated by another of their projects, the Bitsy Boutique, a hardware player for Bitsy games made using a PocketCHIP mounted in a jewellery box.

“I wanted to work out how to elevate Bitsy games from individual web games into something you could exhibit somewhere,” explains Mark, “To get it in front of people who aren’t playing tiny webgames already. The response from creators has been unanimously positive so far, people are excited to see their works recognised as part of a larger whole.”

Its first showing has just been announced for Rezzed’s Leftfield Collection. It's one of the ways Bitsy is starting to move beyond online spaces. There are meetups in Brighton and Seattle, and Claire and Mark are working together to host one in Bristol. Claire is also hosting a workshop to teach kids to make games using Bitsy (she’s previously taught her Dad).

“Seeing the community take shape has been the most magical and inspiring thing about working on Bitsy.” says Adam, “Without their creativity and hard work, we wouldn't be talking about Bitsy right now. All the ways they use the engine has driven what I've added to it, and given me the energy to keep working on the project.”

This energy goes both ways. The community sprung from Adam’s willingness to listen to thoughts, questions and feedback. He's also the host of a monthly game jam that has inspired many to make their first game. The community hasn’t sprung up from nowhere: Adam’s recognition of its importance and his willingness to nurture it is a reason for its growth.

“The community is crucial for people who are maybe making a game or sharing one to a wider audience for the first time,” says Adam. “It helps people to see that it’s accepted and celebrated to make something small, or personal, or incomplete.”

Read on for a collection of the best Bitsy games.

Realm of the Dread Sorceress by Ben Bruce

Ben Bruce is one of the most prolific Bitsy authors. He’s made games that are personal reflections on marriage and dating, about getting your cats to go to sleep, as well as writing guides for the community.

Realm of the Dread Sorceress is the sort of game Bitsy was created to make, letting you explore towns reminiscent of old 2D RPGs. There is a lot of cleverness here. Every community you explore is fascinating from vikings cursed to be forever drunk to a town of cats worshipping a strange idol.

Lil Onion Detective by Tanya Zvezdina

There’s been a murder and you, the lil onion detective, are going to solve it. It’s incredibly charming, with bright colours and cute characters. Interrogate suspects, find clues and work out who done it.

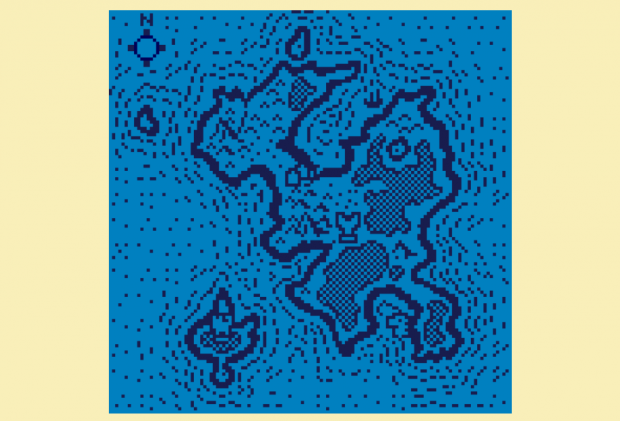

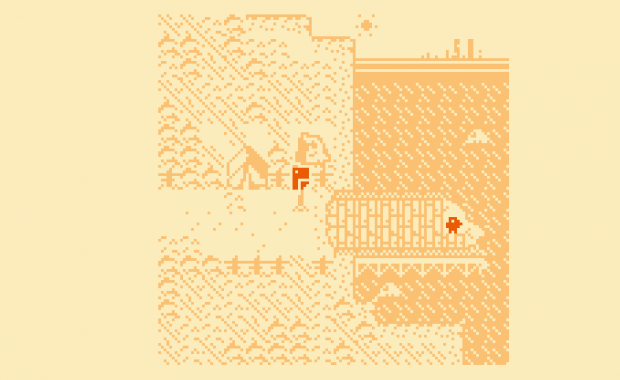

The Exile on the Long Shore by Natalie Clayton

A fragment of a journey. Orange tones paint an abandoned landscape where the only life grows through the cracks. The game’s reluctance to over-explain helps create an alluring world filled with mystery. Part one, made with flickgame, is also available here.

Tutorial by Claire Morley

A love letter to Bitsy and the form. An autobiographical piece that explores how she discovered Bitsy, the challenges of making her first game using it and her fascination with the form.

Also check out her vignette Limbo Train. Put some music on, load up the game and watch the world go by.

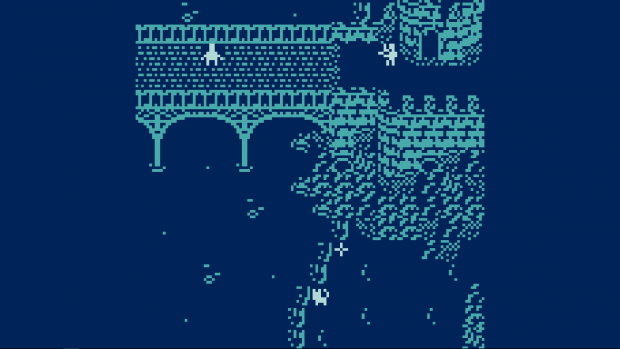

Flotsam by Mark Wonnacott

A cursed tower watches over the crashing waves. Around it strange companions make their homes - a poet, an astrologer, a revolutionary. There is treasure here - junk and miscellania that will help you brave the tower.

Little Treasures by Michelle

Welcome to cat town. Search a cute, pastel-coloured town looking for treasures to take home. The room design is incredible, with intricate backgrounds that interlink in interesting ways.

Silverybield Foss by Ed Key

Proteus creator Ed Key conjures up the moods and feelings of hiking up a mountain. The landscape is often sparse, bleak and intimidating. Plain language narrates our journey as our purpose is slowly unveiled.

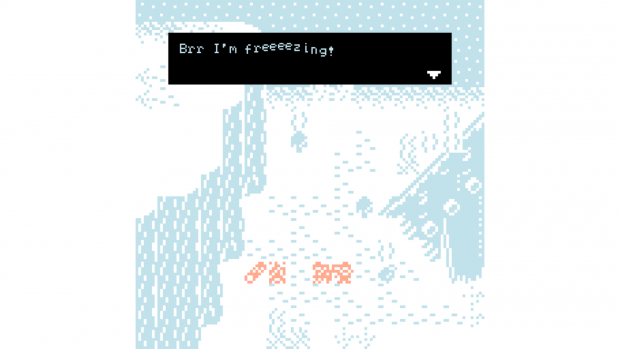

Snowcrash by Breogán Hackett

Your plane crashes into the wilderness as you’re travelling home for Christmas. The key to your survival are the items you can find amongst the wreckage. It has a choice system, forcing you to consider the lengths you’d go to survive.

Day in the Life by Night Driver

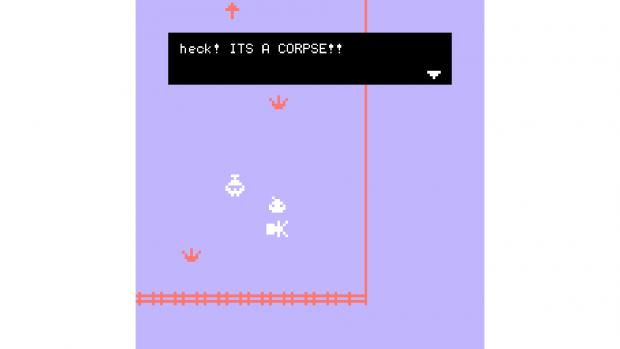

You are a moth in the nighttime. Follow the lights.