Mortal Kombat's fighters are growing up, even as time collapses around them

Netherwhelmed

In the second chapter of Mortal Kombat 11, it's reasonable to believe the world is going to end. Beloved characters have died. Long-slain demigods are rising from their graves. The fabric of time itself is breaking down, and the greatest problem faced by Johnny Cage in this moment is that his unrepentant asshole of a younger self won't take his feet off the table.

It’s a small portion of a larger scene, an emotive moment of frustration while discussing the fate of the world, but it goes a long way towards expressing why I love the writing in NetherRealm’s most recent fighting games, despite the unfortunate work conditions they were produced under. Among just generally good storytelling, the studio’s writers seem to focus on a larger idea. In epic struggles of good and evil; light and dark; cool ninjas and other, slightly more edgy ninjas; NetherRealm’s writers remember the most important conflicts of all are personal.

You can see an emphasis on storytelling cropping up in the studio’s work starting with Mortal Kombat X. It looked forward after the slight reboot of the series introduced by 2011’s Mortal Kombat. The tenth game introduces the concept of legacy, with characters like Sonya Blade, Johnny Cage, and Jax Briggs all having children that participate in yet another dimension-spanning conflict. Characters like Cage also evolve, becoming more mature, when the series could have stuck to the status quo. Unfortunately, the story of Mortal Kombat X is not without its issues. It requires a level of familiarity with a convoluted timeline and parade of characters that leaves newcomers out of its greatest triumphs. The scope of the story is apocalyptic, but lacks gravitas. Earthrealm is on fire, but reasons to care are long-coming. For some people, like me, it never came.

Fast-forward to Injustice 2. It’s 2017, NetherRealm makes a game about photorealistic DC superheroes beating the stuffing out of each other, and I’m having feelings. The story is again about an epic battle between good and evil, with the added challenge of characters duking it out over abstract concepts like the application of justice, and what an ‘acceptable sacrifice’ looks like to a superhero. However, the approach here couches these high-level conflicts within personal stories that make them both more approachable, and more compelling.

For example, Green Arrow and Black Canary are an adorable couple with a family, tossing around jokes and small acknowledgements of care between their respective matches. Would I play a game entirely about Green Arrow and Black Canary trying to have a quiet date night while Batman takes care of the kids? Absolutely. However, the brief interludes here are a close second. These character-based sections aren’t deviations from the core plot, but in fact enhance it. You might not care about the fate of the world, or the evil schemes of a giant telekinetic gorilla, but bringing these two characters home? That’s something worth fighting for.

You can also see that idea of personal-story-meets-epic-threat in Tom Taylor’s three-year run on the comic attached to the first Injustice game. In that comic, Harley Quinn is not only redeemed, but humanized. Her turn as a legitimate hero in Taylor’s run is mirrored in how she beats the manifestation of her trauma with Joker to a pulp during Injustice 2’s campaign.

Injustice 2 isn’t a perfect game, and it doesn’t always manage to frame its apocalyptic conflict with personal drama, but it is effective as a whole. It took playing Mortal Kombat 11 to recognize flaws I previously didn’t see in the game, or ignored. Mortal Kombat 11 is a game whose storytelling always exists on two fronts: the epic and the personal. The personal comes first, because it makes the epic understandable. There’s probably a fancy term for the specific concept I’m detailing here, but let’s call it dual-level storytelling. World-ending stakes don’t mean much if you can’t see the individual lives they affect, and NetherRealm’s growing recognition of this idea has made Mortal Kombat 11 their strongest story yet.

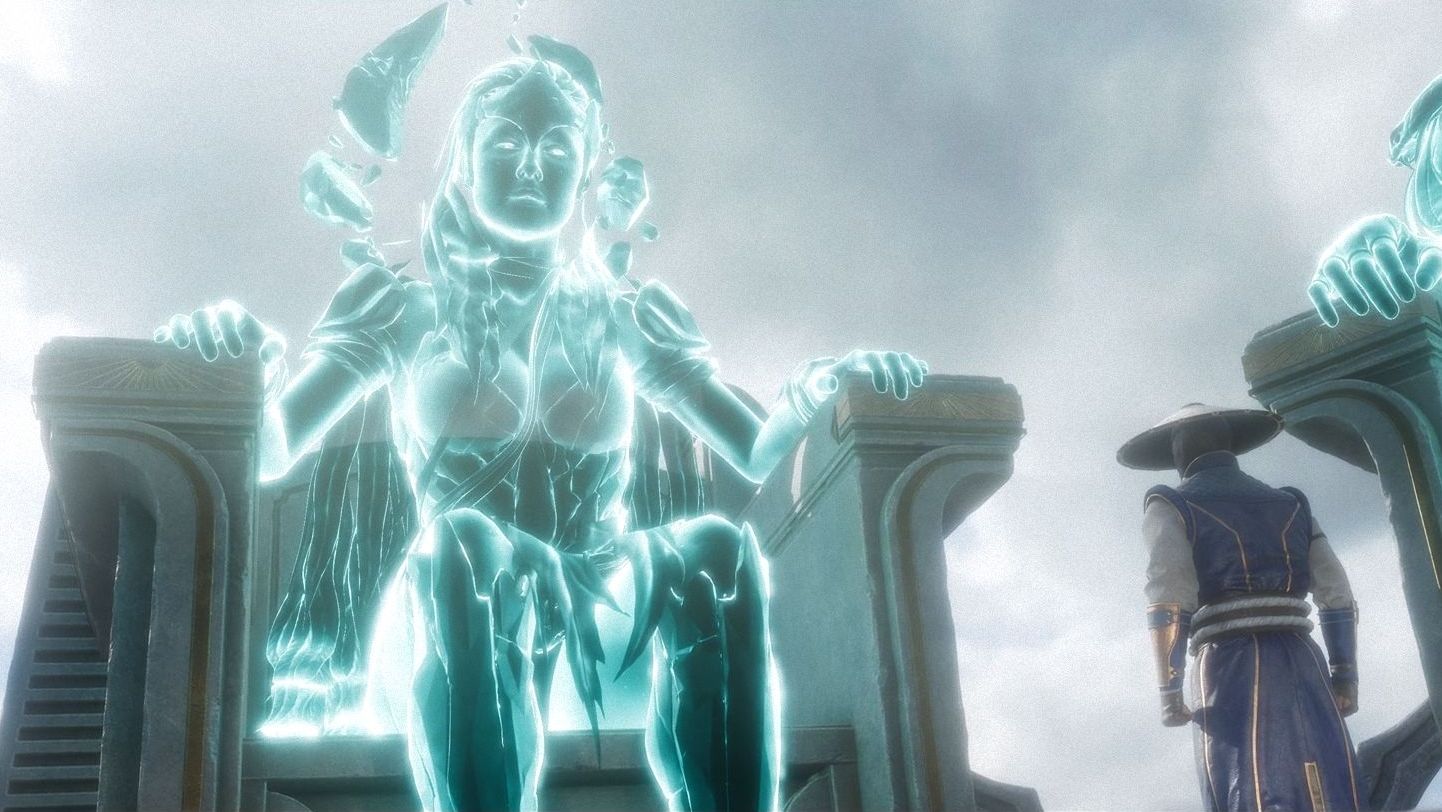

In this fighting game, the primary threat is a new villain called Kronika, who inflicts revenge on the whole Mortal Kombat series by smashing together timelines after her son is tortured by the lightning god Raiden. When a younger version of Raiden appears before the council of Elder Gods who govern reality, he warns them about Kronika’s time-bending schemes, while exposing personal fears about his own future. We’ve already watched a sadistic, older, and irrevocably hardened Raiden die soon after the game begins. Will he become that same tyrant? The Elder Gods state that his future isn’t set in stone, but we still see doubt somewhere in Raiden's lightning-filled eyes, a surprisingly powerful image. This is the epic made personal, and more compelling.

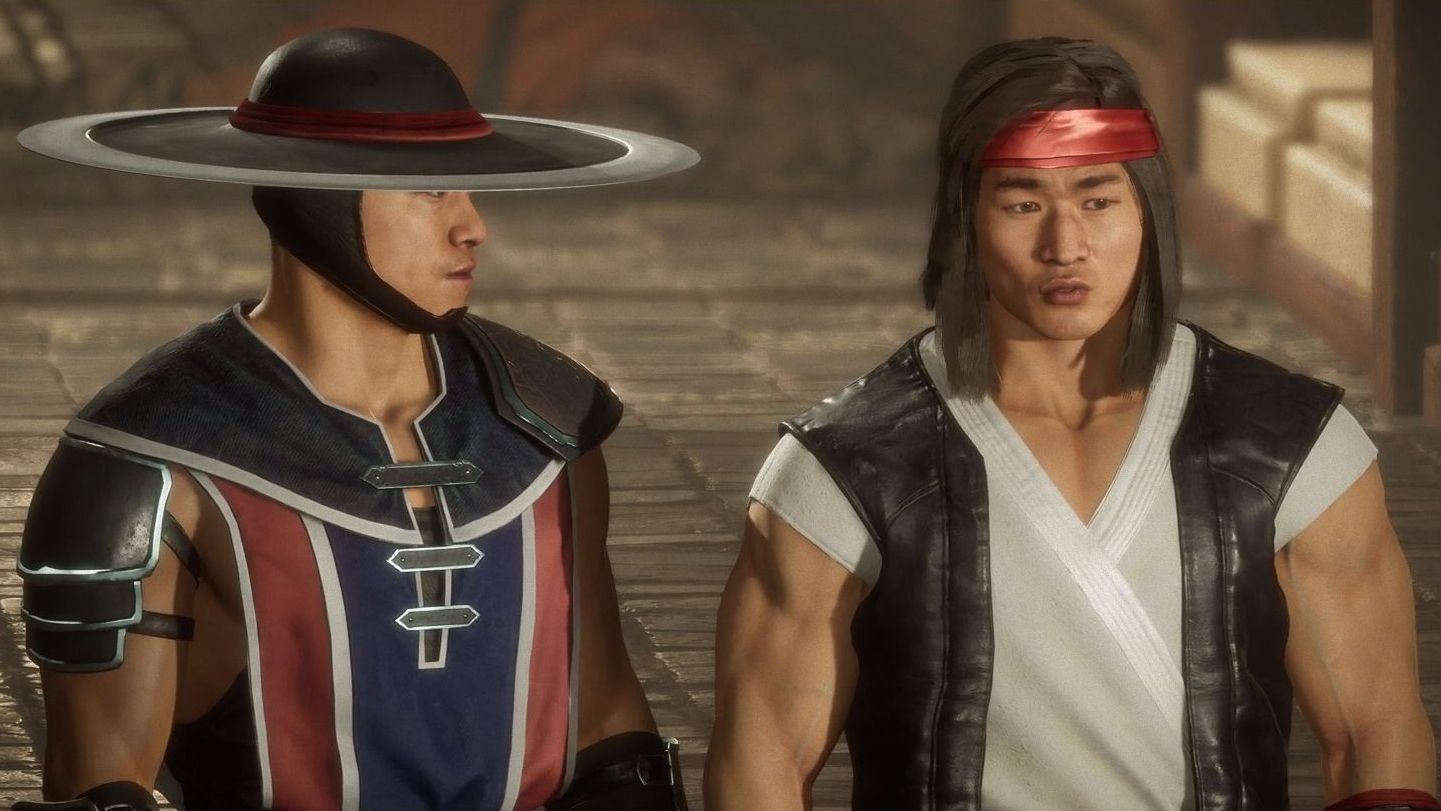

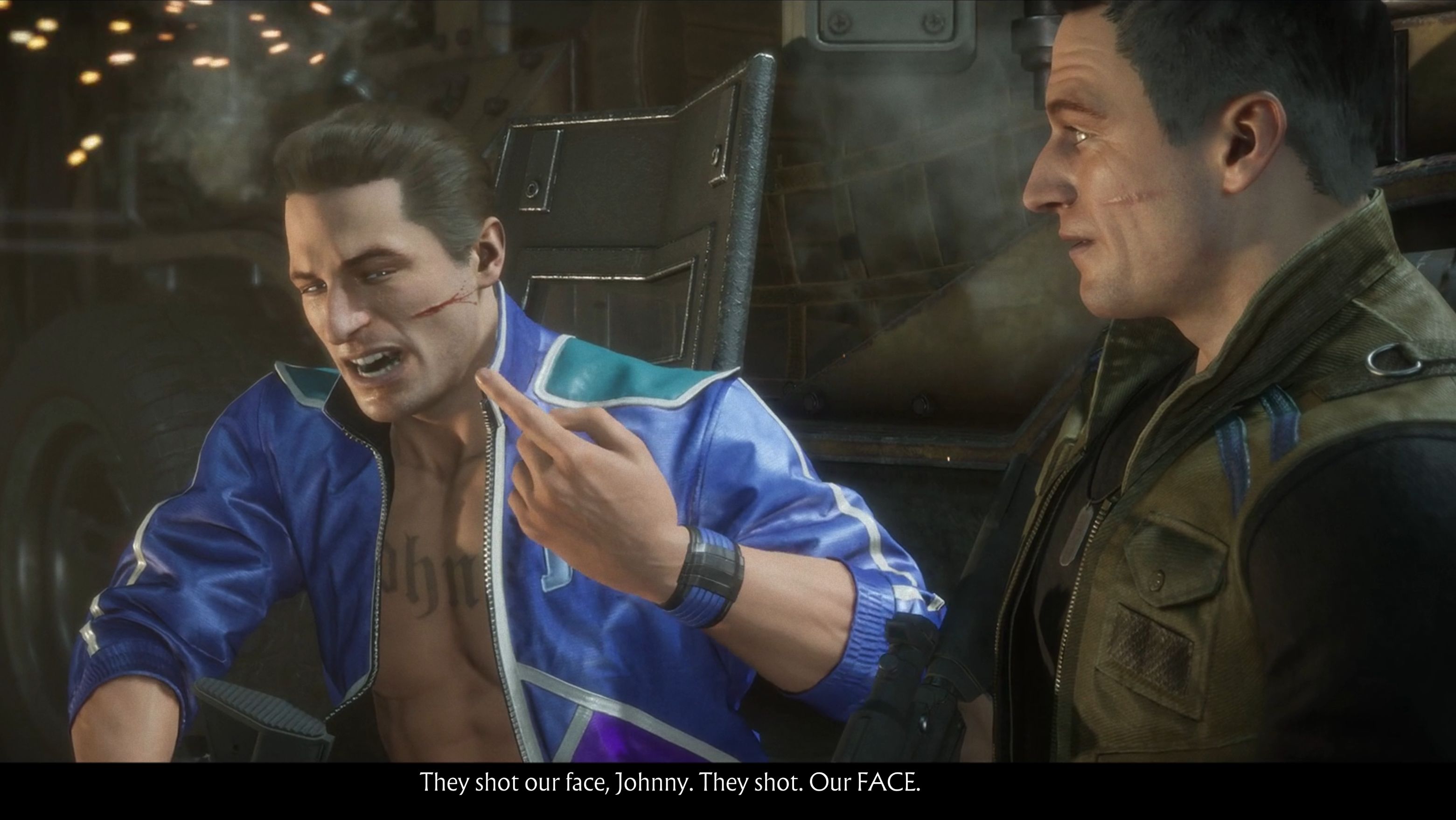

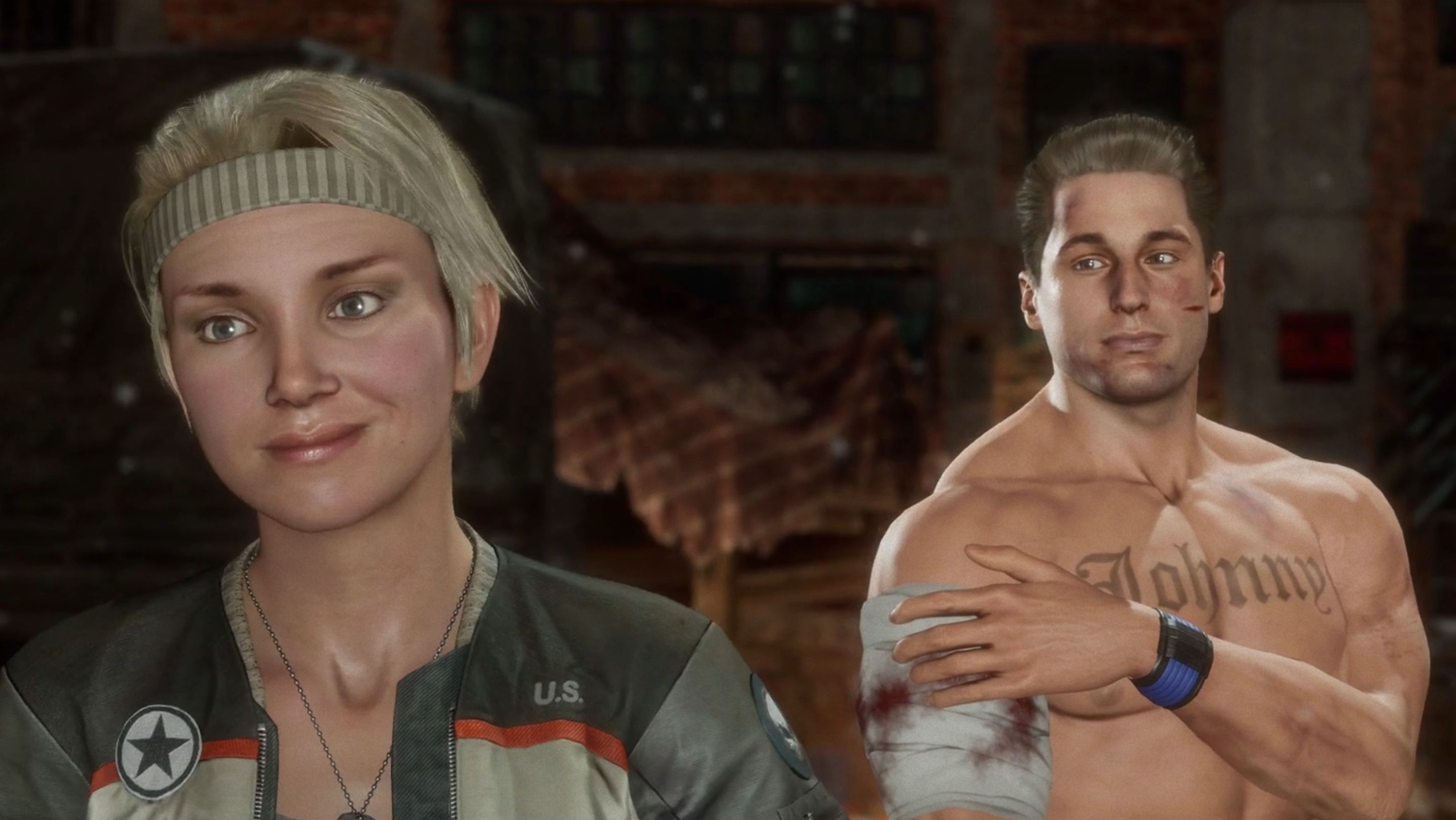

Johnny Cage was one of the big jokes of Mortal Kombat. An inexplicably famous, arrogant mess with magic powers, he went from being a guy who tattooed his own name across his chest in garish font to starting a family with one of the most legendary soldiers of the Mortal Kombat universe, Sonya Blade. In short: he grows up. The older version of Johnny Cage we see in Mortal Kombat 11 spends the game having to deal with the man he used to be, and chafing at the very thought. At one point, Cage kicks the ass of his younger self for making a crass comment about their future wife. Immediately after this, several of Kronika’s agents arrive to cause trouble for some of the cast. One of their bullets slashes young Johnny’s face, creating a scar on the elder Cage’s face while his younger self freaks out. This section is poignant in its comedy. We realise that if the jerk dies, we also lose the seasoned man we’ve grown to admire.

Even later, young Johnny asks out the young version of his future wife in at least one timeline (bear with me). Sonya turns him down. He watches his maybe-future wife walk away in silence. At this point, we’ve seen Johnny be a sexist kung-fu-hole for several hours, the exact character fans have known for years. We've also seen the elder Cage planting a seed of personal growth, the idea that Johnny can be better than this. Now, we get to watch that seed bloom. Johnny doesn’t push the question. He lets Sonya go without a word, because if everyone wins, they’ll have time.

Johnny grows up all over again.

That’s the thing about this “dual-level storytelling” emerging in NetherRealm’s recent work: it makes you care more about the events at hand, and tells you about the people involved. The dramatic stakes in Mortal Kombat 11 are among the most perilous in their catalog. We’re crossing dimensions, space, even time, yet the storytelling remains lucid. The game is accessible despite decades of history, because all I need to know about Raiden and Sonya Blade and Johnny Cage and the rest of these improbably allied characters, is within the game itself. I played some of the original Mortal Kombat games, and a bit of Mortal Kombat X in preparation for this piece, but I don’t know my Sektors from my Saibots. But Mortal Kombat 11 had me cheering for people I felt I had known for years. Cheering! In my shared living space. At 3 AM.

I don’t finish many games, but I blitzed through Mortal Kombat 11. Its message, the message of successive NetherRealm writing teams, resonated with me - the personal is epic.