Wot I Think: Objects In Space

Press the big red button

There are asteroids clanking against the hull. I can’t see them because my spaceship’s cockpit doesn’t have a window. But I know they’re out there. The radar says so. There goes another one. Clank. The computer bleeps at me sadly. Light hull damage, it says. Finally, the clanking stops and my jaws unclench. We’ve cleared the asteroid field. Time to deliver some rare vids to a shady art dealer called Ezra, who's waiting for me on a nearby space station. This is Objects In Space, the low-poly space sim that leaves early access today. I’ve been a well-behaved pilot so far, delivering oxygen for pennies and taxi-ing passengers from station to station. But Ezra is about to make a scoundrel out of me. Because Ezra has a disgusting amount of money.

As space sims go, it has a solid sci-fi setup. You’re part of a ten-year journey to colonise a distant patch of space, the Apollo region. You’re flying a small shuttle and are about to make the final jump with the rest of the fleet, guided over the comms by Wendy, who is both your pal and tutorial lady. But something goes wrong. The jump goes ahead, but your shuttle blops out of it in the wrong place. And, uh, 45 years late.

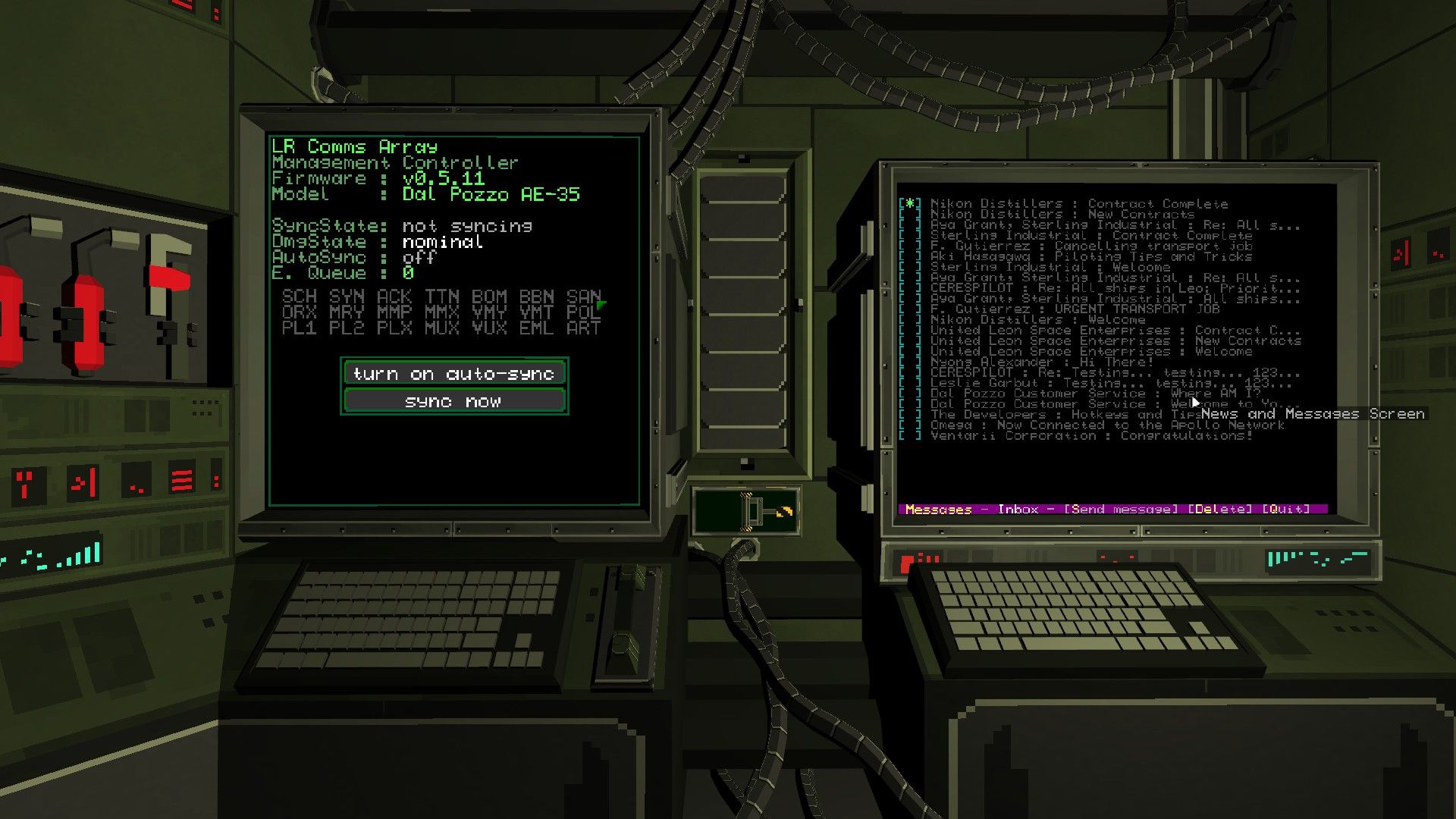

You’re also spinning. A lot. This is when you're taught how toy-like this sim is. This is not a ship you fly with a controller, it’s something with screens and levers and buttons and terminals and components that can get fried and have to be replaced by hand. To stop spinning, for example, you have to find your RCS module (the bit of the ship that controls some thrusters), disconnect it, unscrew the panel, click a button, drag the burnt-out component into a tray, replace it with a working component, then screw it all back up again and reconnect the module. At which point, the ship can right itself.

That sense of having a big ship with lots of tiny parts is exciting. It could also be massively intimidating, as well as being a little scruffy. You’re not walking around here in first person, you’re swapping between viewpoints by pressing left and right arrow keys. Travelling from engineering deck to comms to the airlock with a blink. Most of these rooms have screens filled with sci-fi gadgetspeak. There are glowing words all over the place. “Solar wings”, “helm control”, “discharge”, “sol calc”. I still don’t know what the acronyms on the left of my cockpit mean. They say “RE” and “RC” and “ME” and “MC”, and each of them has a little glowing light. I don’t understand the significance of this. But that is basically the joy of this game. It feels made for those who love pressing buttons. How else would you learn to fly a ship, after all, than by pulling -– oh I don’t know -- this big hazard-labelled lever?

Oh no. The reactor’s gone off.

Still, it’s not as confusing as it sounds. Flying the ship is as simple as clicking a bit of your map and pressing “engage”. Or you can use the WASD keys. A lot of time is spent considering the map screen, making sure none of the other ships flying about are launching torpedoes at you. Dropping into a stealthy flight mode when you see an “unknown signal” approaching you like a scary space shark. You get to punch a big button to do this, which makes a bunch of systems shut down, cutting your “emissions” to the point of quietly floating along. It feels tense and satisfying to glide right under a space battle between an authority vessel and a pirate who has been caught in the act of space-mugging some freighter.

But you have to turn off the stealth mode eventually, since it drains power from the reactor. A friend described all this button-fiddling and blind space-weaving as driving an interstellar submarine. That’s a good way to look at it, as basically Das Spaceboot. That atmosphere is strongest in the seconds following a jump. When you jump, everything goes blue and all your screens and systems reboot. For about five seconds you’re completely blind as the OS on your navigation screen boots up. Some might find themselves yearning for the spaceship equivalent of an SSD drive. But to me this is lo-fi sci-fi at its fi-nest.

There is still a recognisable order to things, as far as the space simmery goes. You land in ports and pick up courier jobs, or fill your cargo hold with wine to sell two jumps away. You take passengers from the central systems to the outer rim, or you collect bounties in the fight against STAR CRIME. But combat involves installing weapons launchers and working out how to use those without getting into trouble yourself. This is something I didn’t experiment with, because I’m not a violent scoundrel. Just a lying one.

So mostly, it follows the rules of the genre. Which means that after a while, you can feel that familiar fetch-questiness sinking in. The space trucker’s spiral. More cargo, more money, more ship parts, bigger ship, more cargo. That feeling was poking at me after a few hours, but there was something keeping it at bay. And that’s just how much character is hidden on these spaceports. I don’t mean the PlayStation-like character models and polygonal billboards (although these things are so beautiful and comforting to a thirty-year-old, it makes me want to cry square tears). I mean the people. Because yes, you do enter the space stations and wander around.

Well, not wander. Each station, like your ship, is a handful of fixed viewpoints, each with shopping panels and monitors and men and women in jumpsuits and gas masks. If one of these people glows blue when you mouse over them, you can click to hear them out. Sometimes they’re passengers, sometimes they’re businessfolk. An early meeting saw me getting pally-wally with a drug dealer, who decided to trust me in brokering a deal. Another meeting had me speaking to an art dealer, who would ill-advisedly hand me those expensive art-vids I told you about, and ask me to be the go-between in an exchange. Sure thing, I said. No problem.

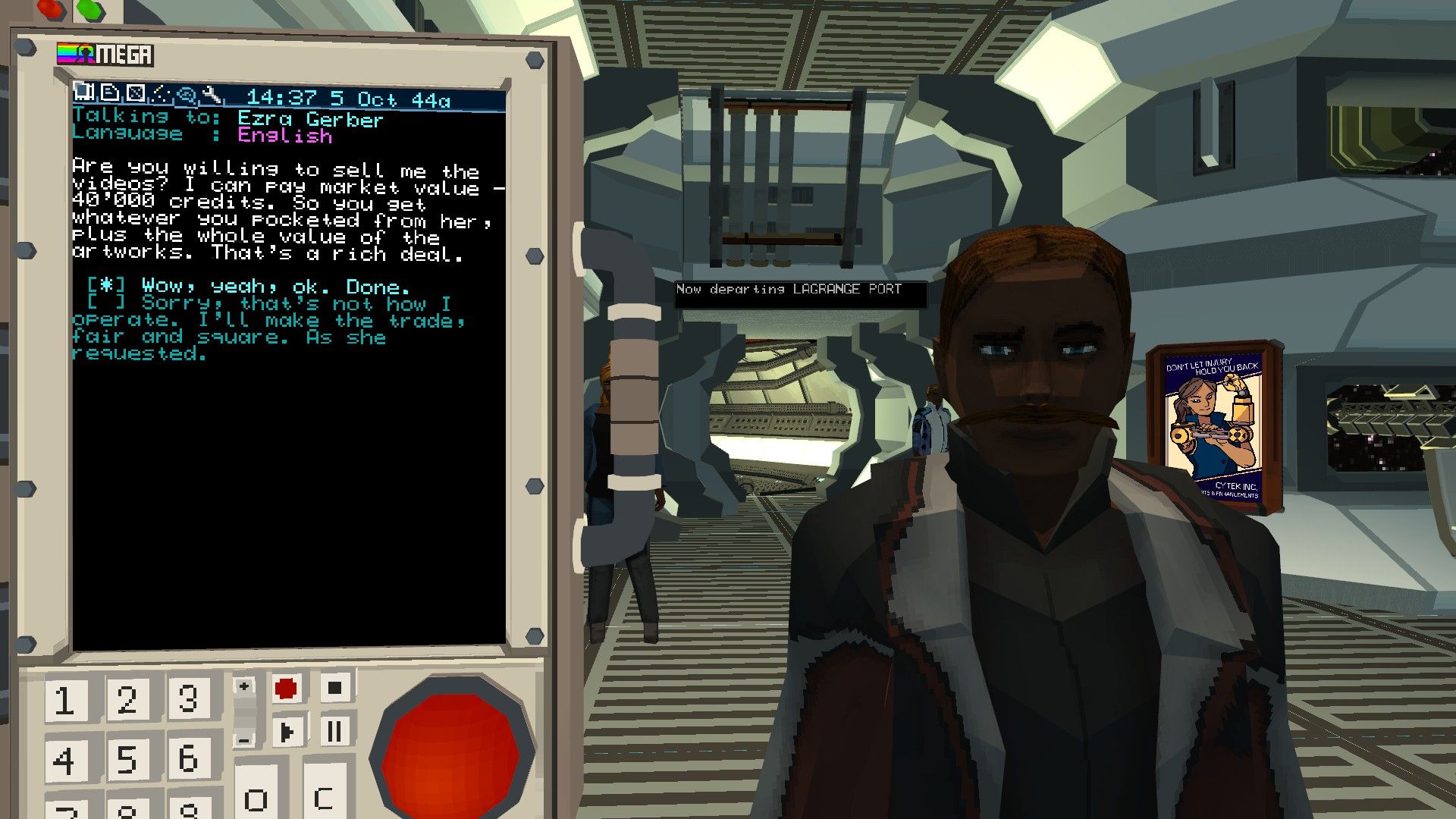

But then I found myself standing in front of Ezra. The guy she told me to meet. Here’s the scene: I’ve got the art-vids in my hand, then he offers me 40,000 credits to stab my employer in the back and just hand them over, without exchanging anything.

“Wow,” I say. “Yeah, ok. Done.”

Here’s where Objects In Space goes from being “space sim with fun buttons” to being “space sim with heart”. I could have refused Ezra’s offer, there was a dialogue option for that. But listen, I normally make anything between 100 to 1000 credits per job. This was simply too much money to turn down. Shortly afterwards, I took out six loans, bought a warp drive, and met a shady Russian academic in a bar who I agreed to ferry to the outer rim. Why not? I was going out there anyway. Where else could I go to get away from the loan sharks?

I was happy to witness these small conversations and choices, because I didn't expect so much handwritten material in a space sim about delivering hydrogen. But I also didn’t expect to see the characters go deeper than this. I was proven wrong again. Later, as my ship wobbled out to the distant corner of the Apollo region, one of my cockpit screens flashed and beeped. It was the old Russian scientist. He was cranky and wouldn’t tell me what he carried in his luggage. But I suddenly recognised his name. Artem… Artem… I’ve seen it somewhere before.

I wheeled over to the long-range comms (I pressed the right arrow to swap between rooms) and typed “NEWS” into the terminal. In the comms room you get emails and news, but you physically have to type in the command line of a terminal to read them. I scanned through the news broadcasts. Aha. Artem Kovalevsky. Researcher at blah blah, retiring after a life dedicated to astronomy, yadda yadda. “We’re sorry to see him go,” said the board of the department. Okay, so he was some researcher. So what.

“They forced me out,” he told me later. They didn’t want to pay an old crank like him anymore. And so he was going into self-exile. Off to the quiet solitude of the Diwali system, the stellar equivalent of the far-flung countryside.

This might sound banal in terms of story-telling. But as someone who loves a bit of space-trucking, it is indescribably refreshing to have some handcrafted characters sprinkled into the mix. And to have two elements of the game (the news screen and the characters themselves) contradict each other in a satisfying way. A bit of RPG with your stellar profiteering. What I would give for Elite Dangerous to have a few personal stories like this, instead of jumbled semi-random flavour text for every tourist from X who wants to see the black hole at Y. And that’s the highest praise I can give this sim. With its buttons and screens it brings to mind the happy days of sitting in a cardboard box and pretending to be a spaceman by drawing crayon radar on the box flap. And with its small character stories, it punches far above its weight as a space sim. All the viewpoint-hopping might make it feel scrappy, a bit dented and rough. But this isn't a game of looking out the window at beautifully rendered stars. It's about being stuck in a big box with loads of buttons and imagining those stars.

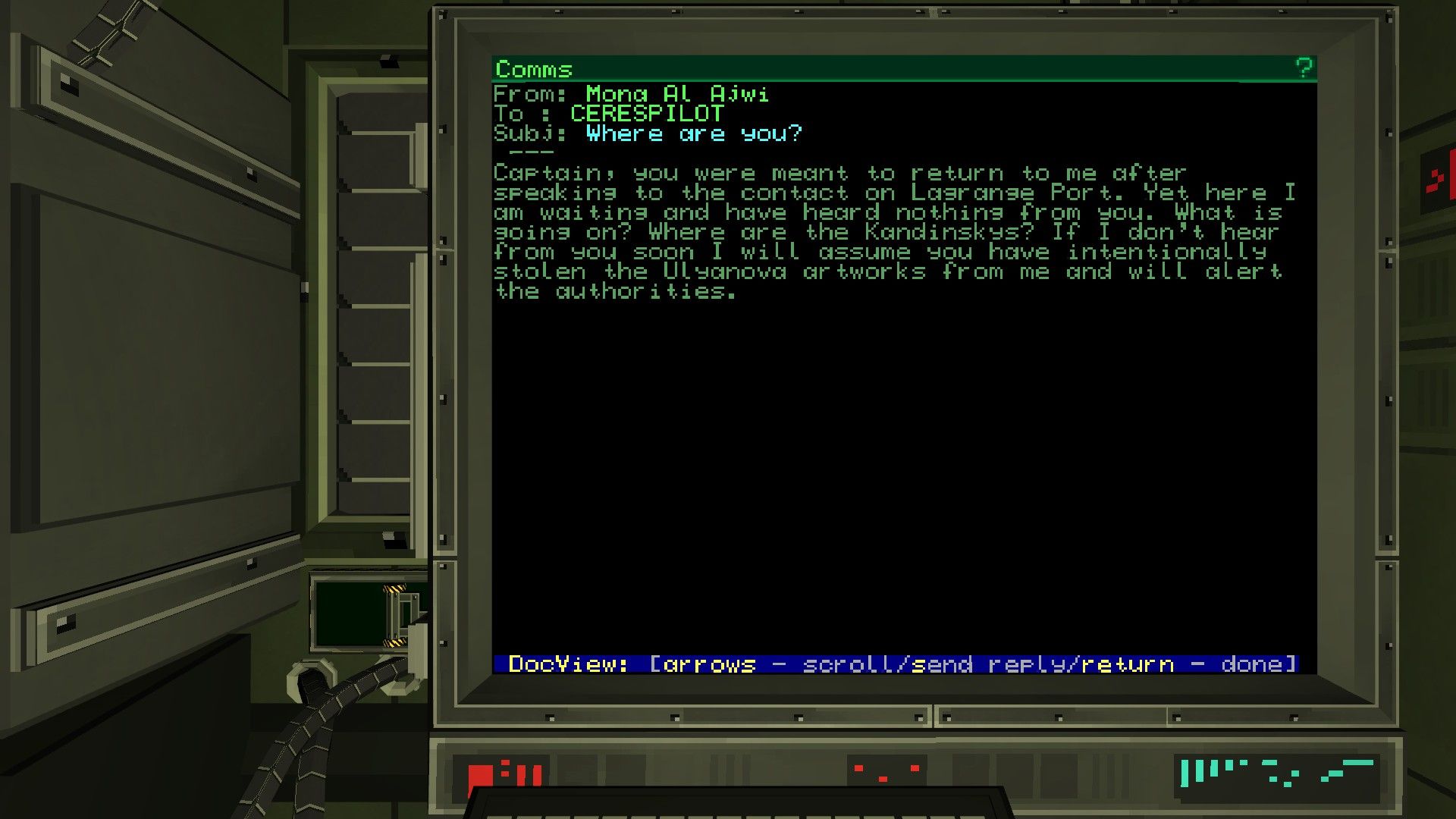

I’ll give you one more incident that made me smile. In the same moment as I read the news article about old man Kovalevsky, I got an email from the art dealer I’d double-crossed.

“Captain, you were meant to return to me after speaking to the contact,” she said. “If I don’t hear from you soon I will … alert the authorities.”

“Sorry, I’ve been waylaid,” I wrote back (because that is another fun thing - you can reply to these emails). “I am on my way.”

“Good,” she said, “you had me worried there. I’ll await your arrival.”

But of course, I was not on my way. Old man Kovalevsky and I were getting out of the central systems and heading to the outer rim. I was 40 grand richer, 45 years younger than I ought to have been, and I still had so many fun buttons to push. Man, it feels good to be a scoundrel.