Premature Evaluation: Objects in Space

Hide and seek

Premature Evaluation is the weekly column in which we explore the wilds of early access. This week, Fraser’s hauling cargo across pirate-infested star systems in space sandbox Objects in Space.

It’s so quiet I can hear the dog breathing as he naps in the hallway. I’ve turned the in-game music player off, killed the power to every component on the ship and I’m hurtling through space. I’m completely blind, so I’m relying on dumb luck to get me to the space station. There’s no viewscreen, no HUD, just a bunch of dead monitors and me, waiting to see if I’ll be hit by a torpedo.

I can’t wait any longer. I pull the lever, the ship shudders and the monitors flicker to life. The torpedo-packing pirate is still close, but safe harbour is closer. I push the engine as far as it can go, and the ship lurches forward. A few seconds later, I see the alert: I’ve run out of power, and systems are shutting down all over the ship. Piece by piece, she’s dying. I’m so close, though. If I can avoid blowing up for a few more seconds, I’ll make it. Momentum alone gets me to sanctuary.

Objects in Space’s sandbox structure might call to mind Elite and its descendents, but trapped in the claustrophobic bowels of my creaking vessel, sneaking my way through the perilous vacuum, I’m equally reminded of Silent Hunter. I’m in a space submarine.

This isn’t a sightseeing tour across the stars, taking in striking stellar vistas and swooshing around massive suns. If there’s a fantasy being fulfilled here, it isn’t experiencing the majesty of space, it’s working a noisy, rickety boat. Instead of staring at the wonders of the universe, you’ll be poring over sensor reports, repairing components by hand and jumping between terminals as you try to keep your ship quiet.

My first ship was a cheap and cheerful freighter. Whenever I encountered threats, my goal was always to avoid conflict. Being a merchant, I was more interested in selling weapons than using them. Were I to actually slap some weaponry on the ol’ hauler, however, Objects in Space would still be a stealth game. Keeping emissions low allows ships to escape potential fights, but it also lets predatory captains sneak up on their prey.

Everything from reactors to comms systems gives off emissions that the sensors of passing vessels can detect, but since your ship is modular, you can turn systems off to reduce emissions. You can do it one-by-one and experiment in the engine room, but you can also link specific systems to the emergency countermeasures button, letting you switch them off directly from the control room. That’s especially handy, as the last thing you want to do is jump between rooms when there’s an emergency.

You might also want to turn things off to conserve power. You don’t need to refuel, but your power pool can only handle so many systems working at the same time, while manoeuvres will also drain your reactor. It means you’re not constantly hitting up the shops to restock, but you still have to pay attention and do a bit of tweaking to keep your ship running as smoothly as possible.

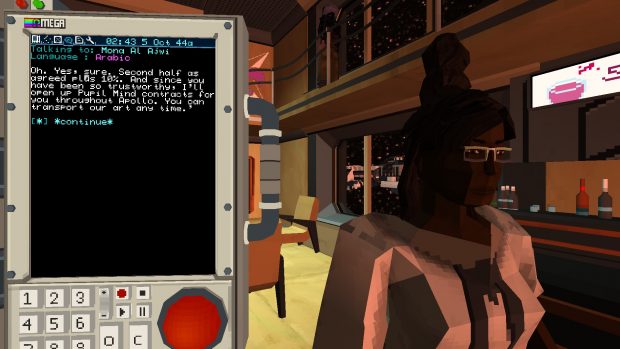

When you go dark, there’s not much difference between the control room, engineering or your quarters. Because Objects in Space uses a diegetic interface, with all information in the game handled by in-universe monitors, turning off the power means you lose everything apart from your PDA. It remains a handy source of information, but it won’t save you when you can’t use your helm or map. At that point you just have to let physics take control until it’s safe to bring your ship back from the dead.

It’s at those times that I do miss being able to gawk at space. Sure, some rooms have little portholes, but they don’t offer much of a view. The claustrophobia breeds tension, but it’s also a little dull. Every connection you have to the universe you’re floating through is cut. Thankfully, going dark is something you’ll only need to do in emergencies, and the looming threat of discovery makes even staring at dead monitors briefly - very briefly - exciting.

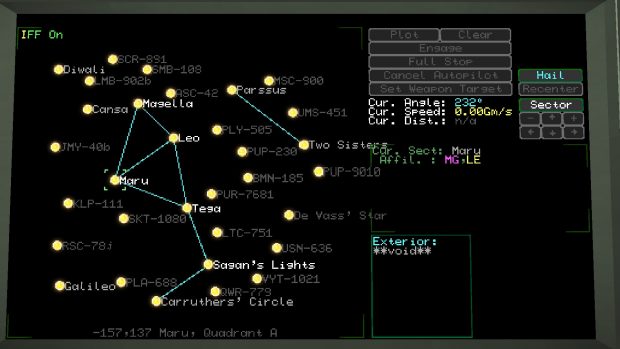

The rest of the time, these monitors - with their simple graphics and pixel font - paint a picture of the universe around you, while giving you fine control over every aspect of your ship. From the map, you can plot your course, using waypoints to avoid asteroids, pirates or the space cops. That’s where you can engage the autopilot, too, as well as look at local sensor data. There’s a helm, sensor screen, comms, tactical and an in-game music player, and that’s just in the control room.

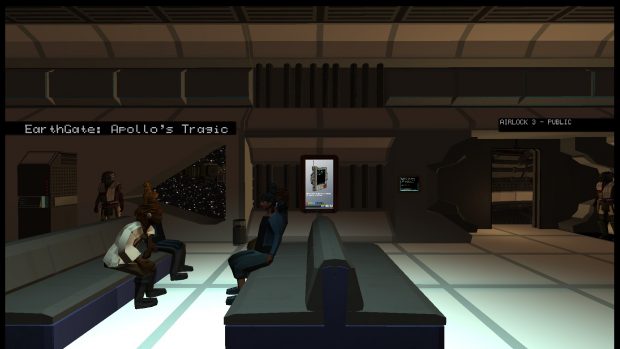

It’s a lot of monitors and a lot of menus. Even when you’re on a space station, you’ll be looking at more of them. But they’re on space ships! And inside cantinas full of smugglers! They’re more tactile than Elite Dangerous’ interface, too. We’re dealing with a ‘retro-future’ here, so everything is a little bit more analogue and less efficient, but it’s also better at making these mundane activities, like buying some batteries, more engaging.

Objects in Space also uses this time, when you’re going from your ship to the store, to spin yarns. Visiting space stations, you’ll meet other travellers, some of whom will offer stories, advice (much needed, since the game hides a great deal of important information) and missions. A quick stop to get a pack of AAs could end with you trying to broker a deal between an art collector and a crook, or meeting someone in need of a bold and pragmatic pilot.

Space sims often skew to the science part of science-fiction, at least to the extent that they use their systems and rules to present a vision of space travel that seems believable, if not realistic. Sometimes that can lead to a universe that’s a bit on the dry side. Elite Dangerous might have ancient ruins and alien menaces now, but at launch it just had boring news reports. Objects in Space doesn’t have that problem. It’s grounded, but it’s not fussy, and it’s got plenty of character.

Set almost 50 years after humans first colonised the Apollo star cluster, and 50 years after you were meant to arrive as one of the first colonists (thanks, space anomaly), there’s half a century of history to catch up on and several squabbling empires to get to know. When you make stops, you can sync your ship up to the mail servers and get news and correspondence, while other pilots can hail you while you flit about, often to tell you off or rob you. So there’s a lot of chatting, and a lot of optional exposition. It’s fairly dense. Thank goodness, then, that it’s all well-written, wry and, if your roleplaying tendencies don’t make you a space-faring arsehole, often sincere.

While chatting with the aforementioned art collector, we blethered on about Monet, Kandinsky, art preservation, heists - it went on for ages. As we stood at that bar I got to know her enough so when the deal went south, I knew what she’d want me to do. I was right and, while she didn’t get what she wanted, I got paid, a reputation boost and the ability to take on contracts from her employer. All because I was happy to get an art history lesson from the future.

Emails, hails and SOS alerts mean that there’s always the chance of something diverting happening on your travels. When nothing is going wrong and your ship is safely on autopilot, there’s not really much you can do, and there’s only so much boredom that the novelty of being in a space-faring submarine can stave off. So a distress call or a message from an old friend really helps break up the monotony of doing milk runs.

It’s still lonely, though. Every ship feels like it’s missing a crew, AI or human. You never really get to be captain because you’re also the engineer, the comms specialist and the tactical officer. With its multiple ship stations, it evokes Artemis and Star Trek: Bridge Commander, but without any of the camaraderie or teamwork. Flat Earth Games does have some multiplayer plans, however, outside of the campaign.

Objects in Space has two modes at the moment: an impenetrable combat scenario and a campaign. The campaign is a sandbox with an endpoint and narrative threads for you to follow, but it will eventually be joined by an endless sandbox mode, absent story, and various solo and multiplayer scenarios. While I’d love to play with a crew or other player-controlled ships in the sandbox or campaign, it’s hard to argue that something built specifically for groups doesn’t make more sense.

When you’re faced with demanding screens and damaged components needing an engineer’s touch (and screwdriver), Objects in Space can seem overwhelming. With an improved help system, however, it might end up being on the more user-friendly end of the space sim spectrum. It’s a lot easier to avoid confrontation than in other sims, travel times are reasonable and maintaining your ship is pretty simple when you’re not worried about refueling or running out of oxygen. It’s complex, but when you actually learn how to use the ship’s intimidating stations, it’s not complicated.

I’ve got enough money for a jump drive now, opening up the cluster and letting me explore previously out-of-range star systems. I’ve a date with an old friend out in the styx. There’s the whiff of a deal on the air and talk of exclusive courier contracts. Maybe there will be enough money for that cargo space upgrade I want. I just have one more job to do before I jump out of the system. I lock in the coordinates, hit engage and start reading my PDA. Moments later, a pirate appears. I turn everything off and wait to see if I’ll be hit by a torpedo.

Objects in Space is out now on Steam, GOG and the Humble store for £13.94/$ 17.99/€15.11.