Emerging Markets: The Brilliant Complexity Of Offworld Trading Company

Nasty, brutish, short

Last week I visited Mohawk Studios to speak to Soren Johnson. His short but impressive CV has one standout entry - he was the lead designer of Civilization IV, a game which I hold in very high regard. His latest project is a short-form sci-fi strategy game with no military component and, in fact, no combat whatsoever. Offworld Trading Company [official site] is an economic strategy game and it's about as far from Civ as a strategy game could be.

Johnson has wanted to make Offworld Trading Company for a very long time. When I ask him about influences he mentions the Market building in Age of Empires, which was home to a fluctuating exchange rate, but it's when he mentions an obscure 1979 boardgame that he seems most excited.

“Belter is a game about mining an asteroid belt that I used to play a lot when I was younger. I always wanted to make an economic strategy game, ever since playing it.”

Fittingly, Belter could happily fit into the world that Johnson and his team have created in Offworld Trading Company. The game, already available in Early Access and due for a full launch soon, takes place on Mars. You play as the head of a corporation that has made planetfall and aims to exploit the planet's natural resources for all they're worth.

What's interesting, and not immediately apparent, is that Mars itself is not of great value. You're not trying to identify rare minerals, chemicals and ores, the likes of which can't be found on Earth – instead, you're mining for aluminium and creating steel from the iron you claw out of the ground. There are chemicals and computers at the far end of the supply chain but oxygen, water, food and fuel can be just as valuable as those top tier resources. That's because running a business on Mars is like maintaining a million Matt Damons; existing on the red planet can be expensive if you don't manufacture the stuff you need to live.

Why go to Mars at all then? Simply building a self-sufficient workplace is tricky and surely the folks back on Earth don't want you to ship steel and poo-tatoes in their direction?

That's where the asteroid belt comes in to play. Although you'll never see it the belt is where the real value in this particular sphere of space lies. There are people working there who have become reliant on Mars for their wellbeing. Shipping food, water, oxygen and food to them from Earth would be prohibitively expensive so Mars, which is relatively hospitable when placed alongside a string of tiny rocks floating in the void, has become the farming community that keeps deep space industry functioning.

All of that is important to the flow of the game, which cleverly defies the 'race to the top' approach that typifies RTS games. I've been there a thousand times, looking at my little patch of land and knowing that my base will have to grow quickly so that I'll be the leader as everybody rushes up the tech tree toward victory. Offworld Trading Company turns that whole idea on its head by tearing down the tech tree and putting a dynamic market in its place.

As soon as somebody starts to produce a resource on-planet, whether it be a necessary consumable like oxygen or an end-product like chemicals or computer components, the monetary value of that resource is at risk. By selling directly to the market, the producer can force demand down causing prices to drop. But by withholding their product from sale, they can achieve the opposite effect.

That means even those goods that are initially high value won't necessarily be high value goods by the mid- or late-game. If everybody concentrates on mining in the early stages of the game, the value of metal products will stay low, as the market is flooded. But if several corporations then switch production to glass, the price of metal will creep higher and higher. In extreme cases, the likes of food and water become extremely valuable toward the end-game when everyone has switched to production of complex resources, neglecting the basics of survival.

It's important to note that you'll never completely run out of a resource, or out of cash for that matter. There will be times when you can't construct a building or upgrade your HQ because you don't have the necessary materials or money on hand, but the market contains an infinite supply of everything you could ever need. As long as you can summon up the cash to buy it, or don't mind slipping even further into debt, whatever you need or want is available.

Of course, if your opponents know that you need a specific material, they can ensure that the price rises and stays high, punishing your short-sightedness. Even energy, the one resource that can't be stored, can lead to punishing expenditure. You'll need it to power your buildings and if the existing surplus that keeps prices low were to suddenly vanish and you hadn't built a production network of your own (in the form of solar, wind or geothermal, each with their own advantages and disadvantages), the cost of keeping the lights on might be enough to finish you.

Brilliantly, Mohawk haven't removed certain strategies in order to emphasise others and despite the dynamic nature of prices, it's still possible to brute force your way to the finish line. In order to sell goods to those working in the asteroid belt you'll need a particularly expensive building, the Offworld Market. I've won a couple of games by directing all of my efforts toward the construction of that Market as quickly as possible, squeezing every other company out of the game by speedily amassing the riches it bestows.

But that's a risky approach and by explaining why, I can describe the complexity of the strategies that unfold over a twenty or thirty minute round of the game.

First of all, if I want to build the Offworld Market quickly, I should be prepared for a reaction from the other players, whether they're AI or human. There's no fog of war on Mars so any reasonably experienced opponent will be able to monitor your HQ and work out what you're doing. The Offworld Market launches massive rockets into space so even someone who isn't paying a great deal of attention can hardly fail to notice its presence.

And when the rest of the players notice one corporation pulling ahead, they can respond using the nefarious arts of the black market. Each round provides eight options for sabotage and interference, ranging from hired pirates who will steal goods in transit to underground nukes that destroy resources on the map. As far as the Offworld Market is concerned, my enemies are likely to cause mutinies, which means they siphon off all of the takings for their own coffers. That's a very simple way to turn an advantage against its owner, and it's possible to defend against such incursions to an extent, but it's one way in which racing ahead of the pack can attract attention and dire consequences.

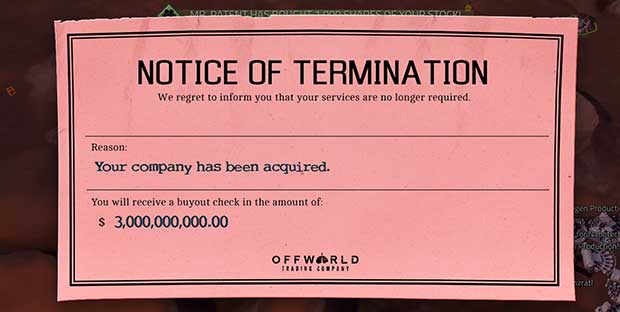

A less obvious but more punishing way to halt my progress would be to initiate a buy-out of my company. Players are knocked out of the game if they become subsidiaries of an opponent and that happens when they lose control of their own shares. Stocks in your company are split into ten slices – you buy and sell 10% of a company at a time – and the value of those stocks is directly related to your debt levels.

To power through the upgrades necessary to purchase an Offworld Market in record time, it'd be necessary to accrue a huge amount of debt. That would cause my stock price to tumble leaving me vulnerable to a buy-out from players who are slowly and steadily building their cash reserves.

In a worst case scenario, if my bond rating hits D, the Black Market, which can both attack and defend, becomes unavailable. Even the nastiest hives of villainy are unwilling to work for you if they're not convinced they'll see a return on their investment. Without access to the tools of the Black Market, a player is exposed and can easily lose control of whatever wonders they've managed to build in the process of creating their blackhole of debt.

The key to success with the Offworld Company doesn't just lie in the value of goods shipped off planet, however, it's connected to the types of goods that have the highest value off planet. Oxygen, water, food. The basics. The things that, in the course of an average round of the game (and there is not really such a thing as an average round given the nature of the fluctuating exchange rates) are of least value. That's because everybody needs them so everybody produces them.

Oh, wait, Robotic corporations don't need them. They operate entirely using energy as a consumable. Robots are one of four corporate types – factions by another name – that add another wrinkle to the game's already complex strategies.

All of this might sound extremely complicated and I haven't even introduced some of the advanced buildings, such as hacker arrays that can manipulate the market to create prices that are independent of the actual status of supply and demand, or patent labs that can secure singular advantages for the first player to research the necessary tech. Patents are the game's equivalent of wonders, in a sense, but their impact is far more powerful. That's because Offworld Trading Company is far more compact than Civ. Everything matters immediately and for the rest of the round.

And that's the brilliant thing about the game and also the reason the complexity ceases to seem...well, complex. Everything that you do matters because everything that you do has an immediate visible effect on those prices ticking up and down on the left side of the screen. You're not conquering a map, although placing your claims should be a careful and deliberate process, and you're not physically striking at an enemy and trying to reduce them to rubble. You're interfering with and manipulating a central system that has the power to change the fortunes of every player in the game. Because you can always see a ripple spreading through the market when you act, playing with the market becomes second nature. Like throwing rocks into a pond.

By placing trust – and a great deal of work – in that core system of dynamic pricing, Johnson and his team have created a game in which strategies evolve and disintegrate on the fly. To play well, it's necessary to be flexible in your approach, reacting to the changing nature of the market and the actions of the other players. It might be smart to dump a load of raw materials onto the market to secure enough funding for a seemingly vital upgrade, but doing so will cause a surplus that forces prices down, which might aid your competitors if they've been craving the materials in question.

For every action a reaction, and for every reaction, a gaggle of CEOs ready to exploit the aftermath. Offworld Trading Company is a game that is explicitly made of numbers – numbers that tick past on the screen, that plummet into the red and that drive your every decision – but it isn't about numbers. It's about social contracts, deceit, trust and hastily improvised strategies.

Learn to look past the numbers and there's an incredibly rich short-form strategy game. It's based around a single idea - the memory of Belter and Age of Empires' market - but that idea is a foundation rather than a totality, and Mohawk have built a set of rules and systems around and above it. You could spend years trying to pick them apart, half an hour at a time.

I spoke to Johnson about the now-implemented "Invisible, Inc. style" singleplayer campaign as well as moving from historical strategy to sci-fi and his reflections on Civ IV. You'll be able to read about all of that that soon on this very site.