Wot I Think: Deus Ex Human Revolution

God In The Machine?

There are very few games that all of us at RPS find ourselves all anticipating so hotly, and this week Deus Ex: Human Revolution is finally with us. Copies should unlock in the US at midnight tonight, while other parts of the world (needlessly) have to wait another four days. Are our anticipations met? I've finished the game and will do my best to tell you Wot I Think.

It’s an extraordinary relief. Like that moment when your shoulders finally slide down into the hot bathwater, you physically and mentally relax in the knowledge that you’re back to that place. Remember when first-person games were complex, multifarious, and had a quicksave? Remember Thief, Deus Ex, Bloodlines? It’s that place, that brain-massaging, hair-stroking safe place of excellence that it was getting hard to remember ever really happened.

It’s worth noting at this point that I have no intentions of going into the intricacies of the game’s plot, any of the surprises in place, and I’m even going to avoid getting into too many of the mechanics of how it works. Much is about free exploration of ideas, and making decisions based on the limited information available and your own personal agendas. Saying, “It’s so great that feature X eventually lets you…” or “It’s crap that X never really gets powerful enough” could define how you’ll play, which would be robbing you of what I had when I started. At the same time, it is necessary to critique some aspects of the game that will by necessity count as such mechanical spoilers. I’m aiming to be extremely careful.

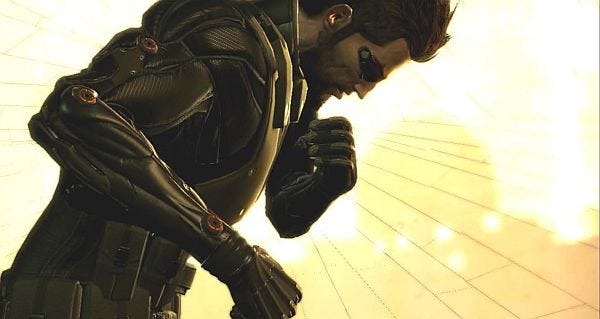

A gentle opening sets some agendas. Following your scientist companion through the laboratories of Sarif Industries, you as Adam Jensen (with the face you’re given) begin on rails. You meet people, watch conversations, and get a feel for the place you work in. Before everything around you goes to shit. It's going to be a game about people, about places, and about conflict.

The central conflict in the second half of the next decade lies between the growing popularity of artificial augmentations for humans, and those who believe in the purity of the human form. A subject that is increasingly becoming relevant to us now, and I think that’s the motivation to have things set so near. Augmentation is already a norm in the game's setting, years before the events of the original, with rival firms around the world competing for dominance in the field, while those left unaugmented fear for their futures. Why would you hire someone who doesn’t have a bionic arm over someone who does? What good is a photographer that requires cameras and equipment when another person can take the shots simply by blinking? And that fear, the sense of a divide and global societal pressure to artificially improve yourself to maintain advantage, is what DXHR aims to explore.

In effect, what this means is going to various parts of the world and sneaking past/stunning/killing lots of people in large buildings, between chatting with locals in the streets. The towns are amazing. Huge locations, without feeling like unwieldy “open city” zombie towns, packed with shops, alleys, sewers and clubs, peopled by individuals with unique attitudes and voices. Although it can sometimes feel like there’s not much to do, there's always plenty of places to go, and various routes to take. You’re generally looking for someone who’s mentioned in a current quest, whether the main, or something on the side. However, talk elsewhere and you can hit glass walls. Once off the street, the chances are you’re going to be in an elaborate office complex with an atrium centre, huge laboratories, and private offices upstairs. Which is a great place to be the first… three times? It’s certainly a fair argument that some locations get repetitive.

Let’s stress the ‘great places to be’ part. They really are. This is a game that gets stealth so very, very right that you start to get angry about games you previously thought were fine. Cover drops you seamlessly into third-person, somehow without this ever feeling weird, and neatly hugs the world’s features. Features that don’t, by nature of the environments, feel like they were put there purely in case some invading combatants were in need of cover. Office equipment, doorways, street furniture and supply deliveries all feel like they should be there, which in turn means you get to feel like you’re manipulating the world to your advantage, rather than the other way around.

And locations genuinely do have multiple routes through them. It’s often hard to appreciate quite how much choice you had until you accidentally stumble on something later. For instance, if you find your way into a building by avoiding bribing the person at the entrance, and instead climbing carefully stacked crates and bins to reach an open duct, then crawl your way in through the tunnels to a cleaning supplies closet, you might later on take a wrong turning and find yourself on the roof. A roof you’ll realise has a ladder leading to a gap where you could jump to a nearby residential building, which you could have hacked your way into and climbed within.

In the end your style of play is met not by the world changing to suit you, but by your simply never encountering the options others might have gravitated toward. And the same very much counts for how you go about dealing with enemies.

I completed the game without firing a bullet. Let alone killing anyone. (With a massively exceptional caveat we’ll be coming to very soon.) Using a combination of tranq guns, the tasering stun gun, and most of all, hands-on non-lethal take-downs, I made sure that the available enemies were out of commission, but without any loss of life.

There was a motivation to play this way, although it came from me, rather than the game – the opportunity to play any game without the thoughtless murder of strangers is enormously appealing. But there was also the option, should I have taken it, of just sneaking my way past most of them without conflict at all. However, that’s less fun! (Let alone that if you knock a guard out rather than kill him, and his body is found by another, he can be revived. If they’re all sleeping, no one’s going to be reviving them.) So my particular tastes were carefully met by the game.

Then again, if they’re dead they’re equally not getting back up. And so while an encountered body will raise alarms (which is why it’s best to hide them well), if you’re killing people they’re going to be under-staffed when they all come after you.

Those are the choices you make on your own. But of course there are others that involve other people. Let’s take the first mission as an example, because it suits and doesn’t give away anything once the story has gotten going.

Terrorists have entered a Sarif factory, and workers are being held hostage. However, your main goal is to recover some technology that you don’t want to fall into enemy hands. You can deal with this in a great number of ways.

My first time, I knocked out enemies I encountered until I found those hostages, and I saved the life out of them. Then at the end, when encountering the terrorist leader holding a gun to the head of one of the hostages’ wives, I used my judgement (genuinely my judgment rather than Jenson’s) to talk him into letting her go, but also let him go free. For my own reasons I won’t share.

I could have, however (as I did in a second play), kill every terrorist, then find the hostages and brutally murder each of them, one begging for forgiveness for whatever it was he’d done wrong. Reaching the end I shot the terrorist in the head fast enough that he couldn’t get a shot off to kill the captured lady, then killed both the police officers who showed up, and stabbed the hostage lady to death.

It’s fair to say this rather extreme approach wasn’t quite recognised by the game. The reaction of colleagues after was not to my sociopathy, but rather to my having killed the terrorist so he couldn’t be asked questions. It’s reasonable to expect people not to play this stupidly, but it is a bit of a shame that it’s possible to do, if the game isn’t going to react to it. But the key point here is: it’s possible to do. As would have been never finding the hostages and their getting blown up purely through negligence, getting into a firefight that saw the hostage wife killed, capturing the lead terrorist to be questioned (I’m fascinated to know what is learned by this route), and all sorts of other permutations. And that’s the first mission. Which hopefully goes some way to getting across the point that this game is so much more than most.

Which makes stupid mistakes stand out like throbbing pimples on a beautiful pristine face. And the pimpliest of them all are the boss fights.

Yes, indeed. This most inappropriate of places has boss fights. Which would be ignominious enough if they weren’t incredibly lousy boss fights. Feeling as though they were programmed by another team, from another planet, they absolutely, unequivocally do not fit in this game. They’re the sort of inclusion that you can only think, “I can’t wait until enough time has passed that the developers will feel able to tell the miserable story of why this happened.”

It sucks that they’re there at all, and it sucks more that they’re all so boring and tedious, lacking even the grace of a classic Nintendo boss fight that at least contains a logical path. But what goes so far beyond just sucking is the betrayal they represent. Here all illusion of choice is gone. All playing styles are abandoned. Playing as someone killing no one, learning that the first fight at least, early on in the game, forces me to kill a man almost put me off the game entirely. Despite only using stuns, EMPs and tranqs on him, I was still treated to a cutscene of a man covered in bullet wounds and blood, gasping his last words as he died. And my clear response was: Fuck you.

I didn’t play for two days.

In the end, the only sensible response is to pretend they’re not there. They have so little to do with the game, and their inclusion makes so little sense, that it’s oddly easy to pretend they didn’t happen. Bizarrely their impact on the plot is minimal, and in they end they’re not actually that hard, so really you can switch off, angrily get past, and then carry on playing the splendid Deus Ex game you were enjoying.

Much more interesting is the augmentation system. As I mentioned, I’m not going to go far into this here. But with hard-earned Praxis Points you can unlock new abilities that define how you’ll approach situations depending upon the order in which you unlock them. Focus on hacking skills and you’re obviously going to do better by breaking into terminals and cracking your way past electronic door locks. But if you’ve been beefing up your arms, such that you can punch through fractured walls, you’ll be more likely to create your own pathway. Again, it’s more choice.

And there was mentioned hacking. Oh, poor hacking. Every game that does it thinks the only method is a puzzle minigame, and DXHR is no exception. Although I’d say it’s the best one so far. It’s not interesting enough to explain in words, but it serves its purpose of forcing you to be in a panic to get into a computer before alarms are set off or patrols wander by. It certainly could have been more interesting, but it never offends.

There’s an accusation that can be thrown at some projects that they’re not nearly as clever as they think they are. But DXHR feels like a game that’s not nearly as clever as the people making it obviously are. And again, it’s not a case of unrealised ambition, or reaching too far. It’s a genuine shame that your companions’ feedback based on your playing style all but dries up after the very first mission, and I think that certainly was a needlessly missed opportunity to capture something that made the original DX special. Perhaps there they simply bit off too much. But beyond that, I felt like it was holding back.

I’ve not mentioned the original DX until this point because I find comparisons pretty unhelpful. But it’s hard not to recall a few of the game’s more esoteric highlights. The books in the game, a combination of technical and fiction literature, were compelling and mostly went over my head as I reached to understand. In DXHR they’re almost entirely technical documents on various aspects of augmentations, whether how they actually work, or discussion over the debates related to them. None made me think.

The conversations in DXHR are wonderfully voiced and impressively acted, and generally very well written. But none made me realise how little I knew about a subject, nor challenged my philosophy on a matter. And yet it felt like, from the atmosphere and attitude of so much of the game, that those creating it certainly could have achieved this. Wonderful stories are told just by hacking into people’s emails and following the threads of conversations from multiple angles. This is a smartly made game. But I fear it’s not actually a smart game. And as much as I may be otherwise determined to not let my memories of an eleven year old game determine my experience and opinion of this one, I wasn’t able to shake that desire to be playing a game that was demonstrably far brainier than me.

It looks good enough, but it’s hard not to constantly feel the struggle for polygons as they fought against the archaic tech of the Xbox 360. The PC version is certainly prettier, and the port is sublime - everything is optimised and works exquisitely with mouse and keyboard. But it’s undeniable that the engine looks dated. (Which is perhaps only appropriately in keeping with the series.) While Jenson’s face looks decent, many NPCs look almost unfinished in the fight to save polys. The cities are big and dirty and interesting, but don’t look too closely or you’ll see the 2D cheats, missing textures, and weirdly blocky backgrounds. This is definitely not a case of crying “consolitus!”, because this is one of the most PC games in years. But at the same time it’s a shame that it has been so obviously visually restricted.

Come close to real greatness and your defects are illuminated by the heavenly glow.

What you have here is a compellingly entertaining game, with some of the most rewarding stealth I’ve encountered. And most of all, you have choice. Choice about whether you mow down enemies with a machine gun, or tap them on the shoulders and punch them in the face. Choice about whether you sneak in via the roof, through the sewers, or march boldly in through the front door. Choice about whether you hack, smash or learn passwords through information retrieval. Choice about whether people live or die. So in those tiny moments when the game robs you of choice, it rather offends. But mostly it does not, and it’s a fantastic, elaborate, and so rarely today, long game.

The most interesting parts can’t be discussed here, because they’re yours to discover. And really, discover them you should. Despite its obvious visual console shackles, this is a game that remembers what PC games were once all about, and honours them. It’s a refreshing reminder of what games can be in the current swamp of six-hour follow-em-up shooters, and stands shoulders, chest and waist above. When games get close to the glory of Looking Glass, our expectations can rise extremely high. That Deus Ex: Human Revolution meets so many of them is a remarkable feat.

Deus Ex is released at midnight tonight in the US, and then for reasons beyond explanation, midnight first thing Friday in the UK.