The RPG Scrollbars: Language Of Uncommon Tongues

Getting your keks

The sign of a truly hardcore world is that it has its own languages. Klingon. Dothraki. Elvish. The term for these is 'Conlangs' - aka 'constructed languages' - and whether you see them as a vital part of world-building or a joke-in-waiting on The Big Bang Theory (they're due a third one one of these days), there's more to them than just slapping together some uncommon syllables and hoping it sounds alien. Well, actually, that's exactly how Klingon started, but never mind. Done right, paying attention to language offers more than just another DVD extra. Or at least, it can do...

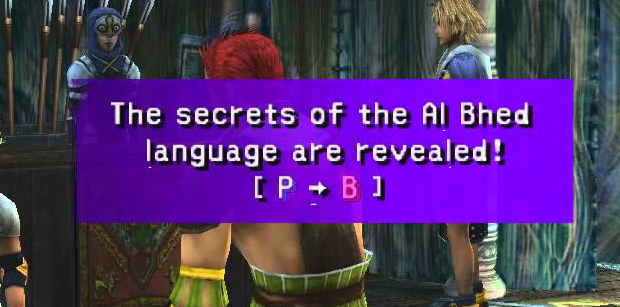

My plan for this week was to talk about a few gaming conlangs and how they affected their world. The catch is that in practice, there aren't that many, and those that exist tend to be simpler than they appear on the surface. The supposed Al Bhed language in Final Fantasy X for instance, while a little more complicated in Japanese than it is in English, is a simple substitution cypher. B means P. Q means X. In Japan, the text is written in katakana to both feel more foreign and allow for easier substitutions. However, the basic gimmick is the same. You collect 'primers' on the language, each of which translates one letter for you (shown in a different colour for clarity), and over time you 'learn' the language not by gathering words or learning grammar, but by collecting the assorted substitutions until the printed dialogue makes sense.

(This would be a lot more tolerable if you weren't generally accompanied by a character called Rikku, who is Al-Bhed and speaks the bloody language fluently. No campfire lessons or offering to act as a translator? No? Okay then. Continue being mostly useless!)

This kind of substitution cypher is however generally a substitution in itself - we're not meant to believe that Al Bhed or whatever is really just English or Japanese after a run through a tumble drier, but a complicated language with its own history and culture and meaning. The average player has no interest in actually learning a new language, and so short-cuts are typically made. World of Warcraft, for instance, enforces a language barrier between Horde and Alliance, with cross-talk being forbidden.

The rules don't usually make any sense, from Undead and Death Knights somehow forgetting to speak previous languages, to the amnesia of switching sides... but never mind. The gimmick is that if you type anything other players will see you said something, but it'll come across as complete gibberish. What's actually going on is that the game takes the word, pulls from a lexicon of words that sound suitable and have the same letter count, and then spits it out on the other side as gibberish words.

Not to be beaten so quickly though, players immediately began creating their own pseudo-language around the translator to do basic conversation - the most infamous being the discovery that 'LOL', as in 'laugh out loud', became BUR or KEK. There's not a vast amount that can be said, but that doesn't mean they haven't given it a go.

(Making this more interesting, the lexicons for the different languages - mostly used in game for individual battle cries, mottos and NPC greetings rather than extended conversations and the like - at least do try to keep each language sounding unique where relevant, or similar to others in its family. Variations of the Elvish tongues for instance sounding a little like the guttural languages of the common Horde member. After all, one would hate to mix a good "Lok'tar!" with a civilised "Anu belore dela'na...")

There are games that dive deeper, of course. Myst for example has the D'ni (dunny) tongue, which is quite spectacularly thought out considering that that it was accidentally named after a toilet. You can get a primer here, starting with rules like words typically being made up with a definitive article, so that 'the master' is 'rehnahvah'. What's interesting about D'ni from a non-linguistical point of view though is that much of it had to be learned by players rather than simply read up on - decoding their base-25 number system, for instance, being one of the puzzles in Riven, done in the suitable context of exploring a schoolhouse. Further exploration reveals that they even have two different forms of writing, one for everyday use, and one for creating or otherwise accessing a magical island full of incredibly boring logic puzzles.

Now, love or hate the terribleness that is Myst, you can't say its birth wasn't a labour of love. RPGs don't typically have the development time or resources to devote to that kind of thing though, unless based on an existing property. Bioware's Jade Empire is one of the few that attempted it with the creation of 'Tho Fan', the 'Old Tongue', which was intended to sound similar to both Chinese and Japanese while being its own unique thing. Despite canonically being the second language of the setting though, pretty much the entire game is in English, the language was only around 2,500 words, and even its creator admitted "I don't know if anyone can tell the difference between this and gibberish." As far as I can tell, there's no information about it anywhere online, save for a few forum comments saying that it wasn't the greatest attempt at a fake language on a technical or cultural level, or added anything much to the fake alien chatter previously used in Knights of the Old Republic.

Still, the creator was brought back to work on Dragon Age. BioWare typically keeps their use of fictional languages to short bursts and phrases that are tonally consistent within a tongue, versus presenting something like Qunari as something that you can actually learn and speak.

(By the way, if you just went "It's called Qunlat!", you are a hyper-geek.)

While that might sound a little unimpressive, it's often enough to do the trick. The Qunari of Dragon Age - which is to say, followers of the Qun, rather than the Kossith/Tal-Vashoth giants synonymous with it - make their linguistics count, most notably with the cultural idea that a person's job is their identity. The party member known as "Sten" for instance is essentially called Warrior, while "Tallis" translates as "she who is geek-bait".

Whether making up words or not, Dragon Age also treats each race and culture as linguistically distinct, from the obvious fantasy tropes of elves vs dwarves, to city elves vs Dalish elves, the different human countries, with the possible exception of the terrible 'Orlesian' accents early on, and slang and bursts of native speech that fit accordingly, even though again, everyone speaks English as their primary tongue. We're not necessary talkin' Tolkein here, but there's just enough to feel foreign while still controlling a character who lives and breathes this world.

It's also interestingly inconsistent much of the time, in the way of real language. "Ser" for instance is a gender-neutral title for knight, as is "Bann" for a low level governor, while at the higher echelons we see feminised forms of titles like Arlessa and Teyrna. This might not seem like that big a deal, but like a lot of language it does actually speak to some deeper elements of the Dragon Age setting - the rough equality of the sexes within it, and certainly there being no surprise that a woman can be a mighty knight or authority figure, even though in Ferelden it does in practice seem something of a boy's club in the middle echelons. This isn't the kind of thing that's ever likely to be brought up by a character in the way of, say, The Iron Bull's discussion of Crem in Inquisition, but it does act as a lingering tell about the setting and its politics, just as simply knowing a few things about the Qunari tells us something about them.

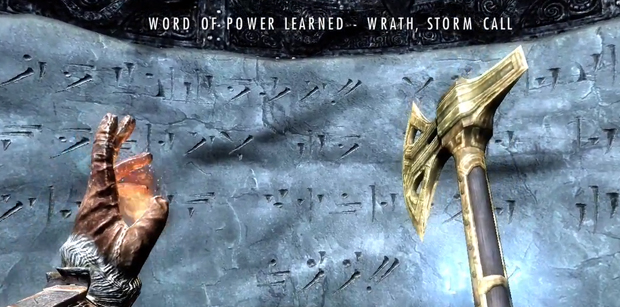

Eevn if RPGs don't create their own languages outright much of the time, it does tend to be something they're good at. Skyrim, for instance, rarely has characters speak in its dragon language, Dovahzul, but that doesn't mean it's not carefully thought out. The structure of it features individual runes representing concepts that can be combined into complex sentences - not a million miles from the long-departed Tabula Rasa. The memetic 'Fus Ro Dah!' for instance is actually FORCE, BALANCE, PUSH. You get this from what initially looks like a wall of glowing gibberish. However, even on that basic level, it has a few key tells that make it feel 'right', not least that every sigil is something that would be carved by claw and talon rather than drawn or painted. Likewise, the dragon characters will regularly use individual words to reinforce that no, it's not just random guff. If you want to, you can even translate the rest - I'm trusting the wiki here, which I realise may be a rookie mistake. Still - in theory - that first one goes:

"HET NOK FaaL VahLOK

DeiNMaaR DO DOVahGOLZ

ahRK aaN FUS DO UNSLaaD

RahGOL ahRK VULOM"

aka

Here lies the guardian

Keeper of dragonstone

And a force of unending

Rage and darkness

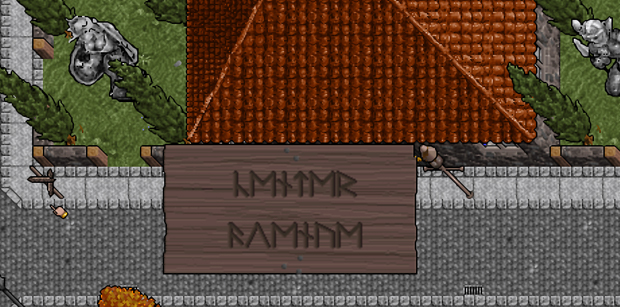

Even when the language is considerably simpler, though, developers can do interesting things with it. Probably the most famous example of a game forcing players to get to grips with another language is the Ultima series, which loved to put runes on everything from maps to town signposts to magic spells. A little like Al Bhed, these are a substitution cypher. The series didn't even invent its own runes - they're called 'Futhark', from the ancient Viking term 'fuck this for a lark, let's use proper letters instead'. (In tribute to that, there were generally translator cheats available.)

Runes though were only one of several alphabets used throughout the series, including the Gargoyle script Gargish, and the Ophidian alphabet, which even the game admitted was a pain in the arse to read, with all of its snake-like lettering. One of the most interesting things about the runes though wasn't where they were used, but where they weren't. Specifically, I'm thinking of Ultima VII - take a shot. One of the big plot points of the game is that times are changing, represented mostly by the evil organisation known as the Fellowship, and one of the subtle details that separates them from the rest of the world is that they don't use the runes.

Their leader Batlin openly calls them out as antiquated, leaving their assorted branches standing out as a shining, modern establishment in an increasingly clunky and old-fashioned world. Provided you a) aren't using the 'translate' cheat, which 99.9% of players do, in tribute to those proud Vikings, and b) don't mind it being a front for an interdimensional demon-god who acts very smug for a big Muppet.

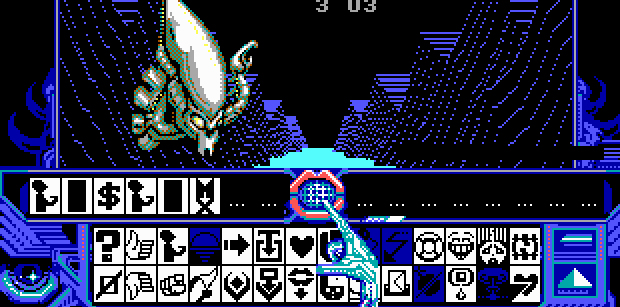

Commercially speaking, of course, there's one game I've not mentioned yet - Captain Blood from way back in the space year 1988. This is one of the few to really embrace the concept of language as a core mechanic, with its conversation system using over a hundred conceptual icons and a big challenge being to try and communicate with aliens in a form they can understand despite not sharing an actual language at all. On top of that, the game was originally written in French, allowing for even more cross-over fun. Much of the game involves not just learning to use these glyphs and their shaky translations, but exploring ways that they can be used, such as the repetition of an emotion translating as an escalation of it versus a simple statement of fact.

The system wasn't easy to use and it's not entirely surprising that its baton remains on the floor. Still, like many games from the 80s and early 90s, it's a great example of mechanics that are still ready to be snatched up and tried again.

Even if it is more likely that the industry will continue of just waiting for Nolan North or Troy Baker to catch a cold and pretending its Orcish.