Steam turns 20 today: "We've had to try a lot of different things over the years"

"Feedback from devs and gamers is always a huge part" of platform's success, say Valve

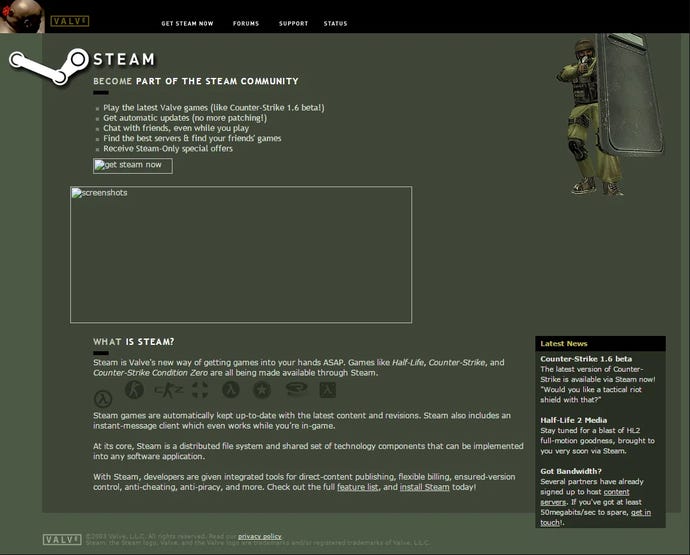

The first time I heard of Steam it was, as you might expect, in conjunction with the release of a little FPS called Half-Life 2 back in 2004. You needed Steam to access it, whether you bought the digital version or a retail copy. Given relative unfamiliarity with digital distribution, the nascent status of broadband internet in the UK and US, and the much greater importance of physical game sales at the time, this caused quite a stir. I remember being alarmed by an op-ed over on GameRevolution.com that held forth at length about the risk of conflicts between Steam and other software, if players were outright required to leave it running. How quaint those anxieties seem today - the day of Steam's 20th anniversary. And yet, there's nothing quaint about Steam's ability to shape the field in which it operates.

Between 80,000 and 300,000 players participated in the Steam beta test before its official release on 12th September 2003. In January 2023, the service scored a concurrent activity record of 33 million users. That's greater than the population of Venezuela. For many players, Steam is simply the air we breathe. Open rivals like the Epic Games Store have so far failed to make much of a dent, while alternatives like the wonderful Itch.io have carved out a niche that is essentially predicated on not competing directly. Steam's rise has also been the transformation of Valve from a video game development studio into a sprawling retail empire. The company relied upon releases such as Counter-Strike and to a lesser extent, Half-Life 2 and the Orange Box, to drive early sign-ups, but the idea that Steam still needs Valve the developer the way Valve need Steam is a fading memory.

It's equally bizarre to think that Steam was once thought of principally as a more convenient way of handling downloadable patches for games such as Counter-Strike (the latest iteration of which, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive is still Steam's most-played game on a daily basis). The original Steam client didn't even have a storefront. And it's probably safe to say that Steam will always exist in a state of hectic evolution.

One of the platform's lingering existential questions is just how big a cut Valve should take from a game's revenues. Another is how to ensure that games without giant marketing budgets aren’t buried. Valve introduced a crowd-sourced submission service in 2012, Steam Greenlight, to speed up the release of new games, rather than Valve doing the "hand-picking" themselves. Greenlight proved unfit for purpose in Valve's eyes, and was later replaced by Steam Direct, which itself led to the introduction of various algorithmic personalisation systems. In recent times, Valve have cultivated a volunteer army of Steam curators, user reviewers and "explorers" to help curate the offering. They have come and, mostly, gone over how actively they should moderate the Steam community for abuse and hate speech.

Steam has an unequalled influence on the culture of both making and playing games. When Valve sneezes, the industry and community catch a cold. Technicalities like the introduction of a two-hour window for refunds in 2015 have had a top-to-bottom effect on how games are designed and thought about. The creation of the Steam Marketplace, following the addition of lootboxes to Team Fortress 2, is one of the most significant steps along the road to the normalisation of in-game monetisation. When Steam relaxed its policies on games with adult content, it led to both a wave of baleful porno titles and a surge in more heartfelt or witty explorations of sex in games. When Valve embraced the early access model popularised by Minecraft, they shifted understanding of things like bugs and helped redefine the relationship between developers and players as an on-going "conversation", for better and worse.

"Our goal with Steam from the very beginning was to make it easier for game developers to reach (or find and start building) their audience; and for players to find games they like (and to get updates on those games)," Valve told RPS over email this week, in a general response to a series of questions about the service's life and times. "Part of that was based on our own needs as devs ourselves, but we were also hearing from groups of developers outside of Valve who really didn't want or need to go the traditional publishing route; they just wanted a way to reach players.

"These have been our clear objectives from day 1, but we've had to try a lot of different things over the years to figure out how to get there. Feedback from devs and gamers is always a huge part of that."

Valve added that "we don't see this anniversary as 'yay we did it!' but more like 'yay everyone on Steam has helped this grow into something cool, let's keep doing it!'"

Some thoughts on all this from Alice0: "I hated Steam when it first launched. As frustrating as it was queueing to download patches from FilePlanet, at least that was a one-off. Steam was there every day, slowing my already-slow computer for little benefit. And one of the main supposed benefits, the Friends list, was soon broken for more years than I can remember. Still, I had little choice if I wanted to keep playing Half-Life mods. Thankfully, over time, Steam improved enough to fade into the background. It's Steam. It's just there. That's where most my games are."

What would the field of gaming be, without Steam? It is a Question, isn't it. I'm interested to read your thoughts and memories. In the meantime, happy birthday Steam.