The Long Journey Home is a wonderful space odyssey

ULYSSES 31

The Long Journey Home [official site] is a game about being lost in space and being somewhat insignificant against a backdrop of elder species who aren’t quite sure what to make of these squishy bipedal nomads called humans. It’s tempting to describe the game by breaking down the list of ingredients that appear to have gone into its preparation. There’s a dollop of FTL, a pinch of Captain Blood, a healthy dose of Star Control and a little bit of Space Rangers 2. Season with the essence of Thrust and Lander, and there you have it.

Except, no. That’s not really it at all.

All of those inspirations certainly seem to have made their way into the game, but the resulting dish doesn’t quite resemble any of them, and feels like its own unique spread rather than a fusion mash-up. It’s a witty, weird and experimental trip that I’d been wary of, but fell for almost as soon as I sat down to play it.

The set up is simple. You pick a crew of four from a collection of ten pre-built characters, each with their own unique starting item, personality, job and skillset, and then get lost in space. Plot-wise, you’re making an FTL trip and end up stranded very far from home, but the real story takes place after the jump. There is an optional introductory segment set in our own solar system, where a tutorial guides you through the controls in the various phases of the game, but for the bulk of your time you’re out among the procedural stars and the planets that orbit them.

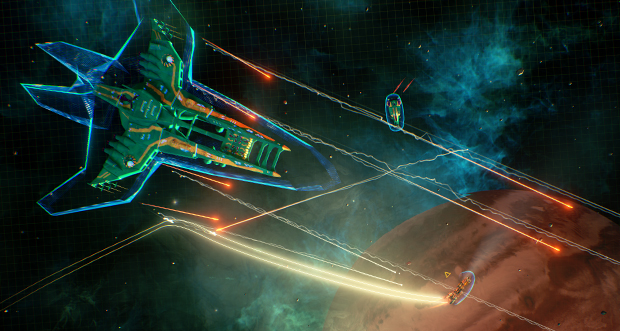

Before you meet the aliens that live out in the unknown, or explore the wonders of far-flung planets, you’ll need to figure out how to navigate each system. I managed to break my crew’s bones before we’d even managed to land on Mars, where a refuelling tutorial takes place. That’s because The Long Journey Home simulates the gravity of celestial bodies, so rather than flying into a planet, you need to use the mass of planets and suns to slingshot as you drift, guiding your ship into a gentle orbit before ‘docking’ with the surface. Then you send out a lander with a single crew member and, depending on the weather and other factors, thrust your way to the surface and whatever useful resources or fascinating mysteries exist there.

Both of these segments, navigating systems and atmospheres, feel like minigames, and they’re good minigames. It took me far longer than I’d like to admit to figure out how to ride the gravitational tracks between planets, but once I had, I found lining up with an orbit so satisfying that I was gliding alongside hellish lava planets that I had no intention of committing my crew to just so I could practice my new-found skill. The lander isn’t quite as demanding, or as entertaining to pilot, but every planet that I saw had a new sight to enjoy, whether a scorching atmosphere or a surface strewn with enormous skeletons, so that jetting about to scoop up fuel and metals for repair at least takes place against a gorgeous backdrop.

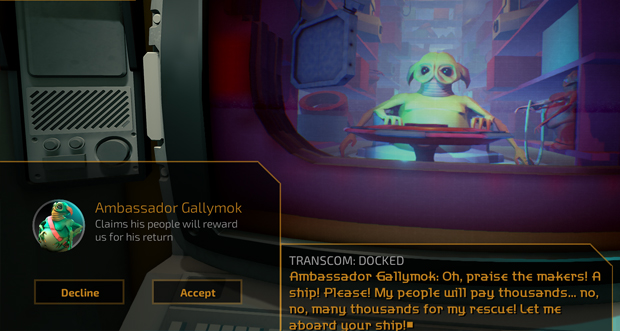

The ship isn’t the focus of the game though – the journey itself is. Each time you play, a galaxy is generated and you’re dumped at the far left sector of that map. Your goal is to make your way from one sector to the next, trying to make your way back to Earth. Right after the jump your crew discover an artefact that allows them to translate alien languages and shortly after you’re likely to meet your first alien species. They might intercept you, forcing an encounter, or you can flag them down and hail them.

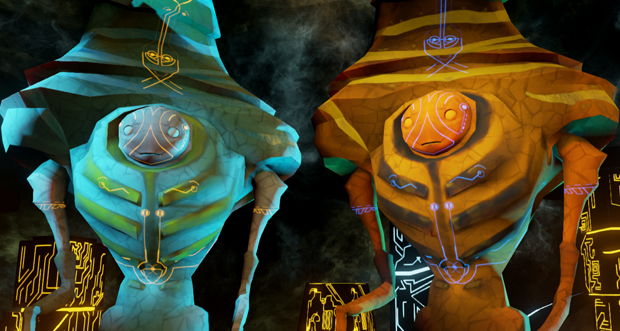

What I love about these encounters is the insignificance of your ship. You’re not the saviours these aliens have been waiting for, you’re just a ramshackle crew of weird creatures from who knows where. Some don’t particularly care about you and trying to tell them about your journey leads to the conversational equivalent of a yawn and quick check of the watch. “Are you done yet?” they might as well say.

Some will try to use you though, asking for help with certain goings-on around the galaxy. I met a chap who seemed somewhat transcendental and he asked me to go down to a planet with a curative device to save the people there from an infection. He couldn’t go himself for... reasons. I trusted him and his ship followed me from system to system as I tried to get to the afflicted planet, a timer ticking down, but I was too late. I landed and everyone had become goo.

Worried that I’d be in trouble for failing so dramatically, and letting the population of an entire planet perish, I panicked and tried to flee, but my ship wasn’t fast enough. Far from being angry, however, my new pal said the blame was all on him, because he’d trusted a ‘young’ species with a task beyond them. Then he gave me some kind of bomb and asked me to drop THAT on another planet to wipe out another infection. That was worrying because he was still tailing my every move and I no longer trusted him. I think he wanted me to do a terrible murder. I also had to stop playing before seeing the end of the story.

The trick is to figure out what each species really wants, how you can help them and how they can help you. Some want to trade, some want to give you quests, and some want to fight. The way you approach them – shields and weapons at the ready or not – can influence their reaction, and I was pleased that a creature that referred to itself as a Knight and kept asking to duel me was impressed when I next encountered it with my guns at the ready. Even though I refused to fight, I’d earned some respect simply by being armed and showing my (meagre) strength.

Some words or concepts aren’t all that easy to comprehend, even with the translator, and that’s where the Captain Blood part of the game comes into play. Anyone who remembers that game, with its spectacular theme tune, will probably think of the difficulties involved in figuring out alien languages through trial and error rather than the plot or the wireframe landing sequences. Journey Home is much simpler, giving you the basics of grammar and vocabulary, but it involves some educated guesswork when dealing with complex linguistic, technological or social concepts.

And it’s all quite fantastic. I haven’t even tried combat yet, though I have blown a few asteroids apart to scavenge minerals. There’s a No Man’s Sky type inventory system, though much more streamlined and less fiddly, for production of fuel for in-system movement and for jumps between systems, and I suspect a big part of the game will involve searching for materials to continue the journey. But there’s a whole other layer, involving the interactions with aliens and that’s where the real pleasures lie. It’s important that the fundamentals – navigation and scavenging – are made so enjoyable though because otherwise they’d just be the busywork in between the fun stuff.

We’ll have a review before release, which is at the end of this month, so I’ll dig into the finer details then, including how well the crew members traits and tales work, as well as combat and any repetition that arises in the encounters. That’s my only real concern, that there won’t be enough mysteries to sustain me across several playthroughs (around six hours is the length of a typical Long Journey, though detours can be very lengthy and entertaining as well). It’s an impressive game already though, helped by strong writing from Richard Cobbett, whose words have been a presence on RPS for many years.

The Long Journey Home isn’t a clone of any of the games that it resembles, but it is both familiar and strange. It doesn’t have the immediate appeal of FTL or the dynamic complexities of Space Rangers 2, but every single one of its components is working at full strength, and the combination is absolutely delightful.