The making of Cobalt Core: how Tabletop Simulator and Inscryption were the secret catalysts behind this clever deckbuilding roguelike

Rocket Rat Games walk us through creating a replayable and reactive card game with just two people

Rocket Rat Games co-founder John Guerra remembers the exact day he started working on Cobalt Core's first prototype. He and his fellow co-founder Ben Driscoll had just spent a week playing Daniel Mullins' mysterious roguelike deckbuilder Inscryption at the end of October 2021, but the combination of a bad storm and a power outage ended up forcing Guerra to decamp from his home in Massachusetts and stay with some family until it all blew over. "I got back late on Halloween, just in time to put out a bowl of candy for some kids, and then the next morning we started Cobalt Core," he tells me.

The pair had been working on a range of different prototypes in the months leading up to this lightbulb moment. As development on their debut game, the spaceship building puzzler Sunshine Heavy Industries, began winding down, "we were throwing all kinds of stuff at the wall," he says, including games in 3D, a platformer, with Driscoll revealing they even had "a Terraria-like one for a couple of weeks" with a grid-based world that characters bounced around in. But it was playing Inscryption that brought everything to a head. Both had spent hundreds of hours with Slay The Spire, but "Inscryption proved to us that there was still a lot of space to explore in the genre," says Guerra. And with increasing calls from Sunshine Heavy Industries players begging them to let them fly the ships they were creating in its shipyard sandbox, "you can kind of see how that went from A to B".

Back on November 1st 2021, however, Guerra and Driscoll were still nailing down exactly what that 'A' looked like. For Driscoll, who's based on the opposite side of the US to his development partner, it was the way Inscryption's cards talked to the player as characters in their own right that captivated him the most. This idea then collided with another one he'd been sitting on, based around "being on the bridge like you're in Star Trek, and having your characters, who have real stories and things to say, yelling commands at you, or offering you options," he says. "Like in the game Reigns, where you have cards pop up and you go left or right for a choice. That was the original thing I was thinking about. Then we ended up on the cards, because they were more fun."

It still wasn't clear what form these cards would take just yet, but Guerra explains "the second we realised how well those two ideas clicked together, while we were both thinking about cards because of Inscryption, we were like, 'We have got to dig into this one.'"

But how do you paper prototype a card game when you live on opposite sides of the country? The answer lay in Berserk Games' Tabletop Simulator, with Driscoll taking on the role of the player, and Guerra acting as the theoretical computer. "That was a really good way of testing really quickly, like, what's working, what isn't?" Guerra continues. "We threw out some ideas early on really fast because of that, and we were able to figure out the core of the game, I mean, honestly, it kind of came together within, what, a few days?"

"Yeah, the game landed very quickly," says Driscoll, "which is why it was the one we picked to finish. It checked all the boxes we wanted narratively and vibe-wise, it made sense for us because we have experience making a game that looks like this and has this character, and it worked mechanically. It's within a space of games that people know that they like already - people see five cards and are like, 'Okay, I understand' - and it was different enough, and had its own character that we'd have fun making the rest of it."

I ask them what might have happened if Tabletop Simulator hadn't existed. Would Cobalt Core still have been the same Cobalt Core we know today? "It's not just that it would have taken longer if we just started coding it from scratch," says Driscoll. "You might just not end up with the same things. It might be too much work. If you make system A, and then you want to try out system B, but it takes two weeks to do it, you might just be well, like, I'm tired, you know?" he laughs. "But it's so easy to change it on paper."

"[Drake's] like a foil to the vibe of everybody else. Her whole existence is just to be rude."

With the core of the game starting to take shape, Driscoll then set about drawing its characters, gradually working out who they were and what their role on the ship would be. Dizzy, for example, one of the three starting characters, was originally "much grumpier-looking" with horns and "cool dots on him," says Driscoll. Eventually they both felt that he simply came across as "a guy who looks tired", prompting a complete revamp. Drake, meanwhile, who's one of the later unlockable characters, began life as an enemy, ironically mirroring the exact way she joins your crew in the final game. "I forget why [she became a crew member," Driscoll chuckles. "We just thought it would be funny if you could play as her because she's kinda mean, and we don't have any characters like that. She's like a foil to the vibe of everybody else. Her whole existence is just to be rude."

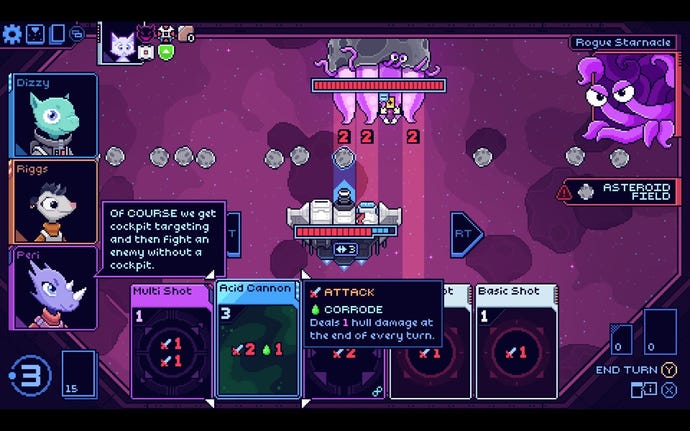

Driscoll also drew plenty of placeholder art for Guerra to use while he worked out the details of the card system, and at one point he tells me there was a "purple slug guy with big eyes" he used for testing out the deck for their seventh playable character. "That guy was very briefly, very briefly occupying one of the player characters," Guerra laughs, "and then Ben was like, 'That guy does not deserve that! No, no, no!'"

"At that point, I think we had a conversation that all the characters are all too cute," Driscoll clarifies. "We already have a cute mammal, we already have a cute possum. If we add another character, we should do, like, a weird one." Guerra agreed with this assessment, but Driscoll quickly started thinking, "What if I just made like, a little - " He stops himself. "What if I just drew Books instead and put Books in the game? And we were like, 'Hm, hm, yes, yes.'"

"And you were right!" Guerra chimes in, but Driscoll is quick to address that brief pause, saying, "I almost… We have this running joke, which is we haven't assigned Books a species, she's just, like, a critter. I almost described her as a specific animal, which… that can't get out! She has a hat on, you can't see what kind of ears she has!"

Some of the enemies you encounter also came from similar, spur of the moment decisions like this, including one of my personal favourites, Brac the Crab. "Brac literally started with Ben saying, 'I want to draw a crab ship, and do a crab ship,' and I was like, 'Great, we're adding a crab!'" Guerra jokes.

"Nature just keeps making pinchy boys."

"No, no," Driscoll says. "The gag was, we were talking about carcinisation, the tendency of nature to make many creatures look like crabs that are not technically like crabs. There are many crabs that are not related to each other. Nature just keeps making, like, pinchy boys, and we thought it would be funny to have two different crab enemies that insist they have no relation to each other, but look very similar. And then we just never made the second," he laughs.

As more characters started appearing on the scene, though, Guerra says that designing appropriate decks for them became "one of the harder design beats." They'd always planned to have three characters right from the start, with the intention of adding more later. "[But] when it actually got to the point where we had swapped from 'there are three characters' to 'there are four plus characters and you choose three', there was definitely a shifting of gears of like, 'Oh, shoot, this card doesn't make any sense anymore if that other thing isn't there.'"

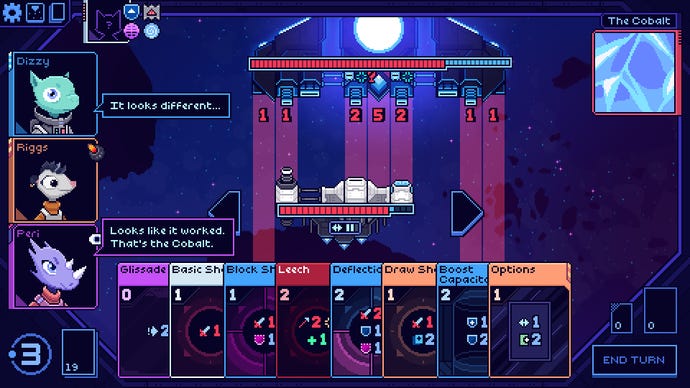

But it wasn't just the card synergies that started going awry. They also wanted to have cutscenes to move the story along, but the question then became "how the hell are we going to do [that] if there's no guarantee that any given character is present on the ship?" Guerra continues. That's when CAT came in, your ship's computer. She's an ever-present force in Cobalt Core, acting as a sort of de facto leader for your crew on each run. However, since she's also the only character who retains her memories between its roguelike timeloops, she's also the glue that holds the game's story together. With her in place, it "cleared up" a lot of problems that Guerra and Driscoll were starting to run into elsewhere, and gave them the surety of always having a constant presence to deliver the game's main story beats.

"If we didn't have CAT and every conversation with every person had to have back-ups for all eight characters that need to be present, that would have multiplied our work by a lot," says Driscoll. "And it probably would have ended in a worse place, because you're trying to write stuff that isn't specific enough."

With CAT on board to do the heavy lifting on the story, it then became the job of the remaining crew members to help bring "more flavour" to Cobalt Core, the goal being to make the world feel just as alive and aware of the player's place within it as perhaps Inscryption's sentient cards did. But even though it's the characters who are doing most of the talking here, Guerra and Driscoll tell me that it's still technically the cards who are the ones whispering inside the machine here.

"Very little of the game's dialogue is fired directly from the code," Driscoll explains. "All the dialogue exists as just a big file organised by conversation, and the conversations have a lot of filters they can use to make themselves get picked by the game at appropriate times." For example, you might play a card that successfully hits for two damage, and once that turn's finished and everything "returns to rest," as Driscoll puts it, the game will sift through that database to find filter out an appropriate response, such as 'Nice shot!' for that missile hit or 'Is everyone okay?' if you miss and take damage.

"It's kind of an illusion, because this is a lot of specific stuff that was easy to add, but it makes your characters feel pretty alive and aware of you, which is cool."

"It's really easy, relatively speaking, to just put more dialogue in the game [this way] without creating more code," says Driscoll, and Guerra confirms that "a lot of the hyper specific dialogue kind of worked backwards from that" once that system was in place. "Why not add a shout that [references] 'if these two characters are on board and you just hit while you have this artefact'?" says Guerra. "There are enough of those in there that I think we keep surprising people with new details that they haven't seen before, you know, 100 runs in, and I love that."

"Yeah, there are ones that are specific to synergies that we know exist between two artefacts or something that [when] a character will say it, players are like -" Driscoll throws his hands to his head in a 'mind-blown' kind of expression. "It's kind of an illusion, because this is a lot of specific stuff that was easy to add, but it makes your characters feel pretty alive and aware of you, which is cool."

Of course, depending on which characters you pick, the emotional trajectory of that dialogue may be more congratulatory than others, as Guerra admits there are definitely "some teams that are easier or harder than others". The three starting characters are "arguably the best team composition," he says, though that's partly because they were designed first. They also embody "the three game mechanics," Driscoll adds, citing Dizzy's specialisation in defence, Riggs being geared around evasion, while Peri, as your weapons officer, is all about attack. "Everything else is just a complication then."

As for the hardest teams, Guerra and Driscoll have several theories. "Most of the combinations with character eight are intended to be a little bit difficult," Guerra muses, with Driscoll proposing, "It would probably be 'Eight', Max and Books, right?" Then again, "all of the boys - Dizzy, Issac and Max - all kind of lack offensive power, and that gets kind of tricky [as well]," says Guerra. Fundamentally, though, "every team comp is viable," Guerra stresses. "We've seen somewhere between five and ten people now post screenshots of 'Hey, I have officially beaten every team comp on the hardest difficulty,' which is awesome. I love that there's a place that they can challenge themselves there."

At the same time, Driscoll and Guerra were both adamant about Cobalt Core having a clear and definitive ending. "That was an intentional choice," says Guerra, partly because they both find games with endings more satisfying on a personal level, but also because, as designers, accounting for ever-increasing meta-progression simply isn't as compelling to them. "I find it more interesting to design the game under the assumption that you're exactly as strong on run one as you are on run 100," says Guerra, though he's keen to stress that he's "not dunking on anyone who's doing the opposite". Rather, "if I understand exactly how strong a player could be at the end of act two, then I can make a tightly honed second boss. Whereas, if it's like, 'oh, at this point in the game, the player has gained anywhere from one to 100 extra max health, it's like, 'I don't know! I don't know how much damage it should do…'"

Driscoll concurs, saying that the only "small exceptions" to this rule are in service of making the game easier to learn - and, of course, to deliver a good punchline in the process. "I think it's a couple of victories until Wizbo shows up," he gives as an example, "and that's just because we watched our friend play, and the first event he got was Wizbo. And if you don't know the context of the game - a sci-fi game at the core - then getting a wizard as your first enemy is, like, you're missing the joke. Why is there a wizard in space? But that's funnier if it's the third or fourth round. You see a wizard and you're like, 'What? Who are you?' Aside from stuff like that, the game is basically meta-progression free except for unlocking new characters."

So what's next for Rocket Rat Games? A well-deserved rest, by the sound of things. "We've been trying to play future stuff a little bit close to the chest, just because, honestly, we worked really, really, really hard for a long time before launch, and now we're not trying to make any promises," says Guerra. "I'm taking my time and it's nice." The pair are definitely "sticking together", though, saying they'd also like to add alternate bosses and "probably some sort of daily mode" to Cobalt Core in the future.

"We are going to make a third thing, though," Guerra teases. He's not sure when, though this is likely because he's currently playing every Final Fantasy game in order - he's on V right now - as well as likely catching up on Klei Entertainment's Griftlands, which he says he "specifically didn't play" during Cobalt's Core's development, just in case it interfered with his own design ideas. "We like making new stories," Driscoll concludes. "I'm not saying we wouldn't make a Cobalt Core 2, but if we made another game, we wouldn't want to probably write about the same characters." Unless, of course, it's Books, or Sunshine Heavy Industries' shipyard mistress Selene, who also makes a repeat appearance as Cobalt Core's resident ship tinkerer. Then all bets are off.

"Books seems like enough of a misfit in the Cobalt Core universe that she'd be likely to show up in something else," says Driscoll, and Guerra agrees: "If our next game was like a 3D game set in medieval years or whatever, we would still just be like, 'Yeah, whatever, and Selene shows up. She runs a wagon building industry in this one.' If we're having fun, you know, it's a playful space."