What videogame maps can tell us about their worlds

The silent cartographers

We don’t expect much of a typical video game map. As long as it guides us to our destination (and perhaps looks pretty while doing so) most of us won’t waste a second thought on it. And yet, maps can be much more than tools that make our way from A to B a little more convenient. Some games reject the notion of maps as a tacked-on extraneous layer, and instead treat them as an integral part of their world. These maps can tell us something about their world and its inhabitants that goes far beyond topographical information. Rather than creating distance between us and a game, they root us more firmly in it.

The Banner Saga trilogy has one of the best in this regard. At first glance, its map impresses with its materiality -- the folding marks, discolorations and parchment texture which make it appear like an object created in the very world it depicts. The decorative flourishes of Norse dragons, constellations, ships and warriors not only give us a sense of the world’s aesthetic sensibilities, but also of its culture, values, and myths. In the second game, the spreading and all-consuming darkness the characters are fleeing spills over onto the map. It appears as a dark and purple pool through which the features of the map become warped and difficult to make out. The Banner Saga map thus becomes part of the plot; a device which conveys a sense of escalation and growing urgency to players by tracing cataclysmic developments in its world.

Before the advent of the darkness, the map of The Banner Saga still gives a coherent, almost encyclopedic view of its world, where clicking on any element will satisfy a hunger for knowledge with tasty bits of lore. Other maps, however, create meaning by refusing to give us the full picture, and handing us incomplete fragments of information instead. In Thief: The Dark Project, for example, master thief Garrett unsurprisingly doesn’t have access to the floor plans of the mansions he’s planning on burglarising and has to make do with sketches full of gaps and guesswork. Not only does this make your thieving expeditions unpredictable and keeps you on your toes, but it also tells us something about Garrett’s illicit handiwork – its thrills and pitfalls – as well as the ways of the criminal underworld he inhabits. It shows a world where information is hard to come by, and in which thieves and their informants go to great lengths to lay their fingers on any scrap of information they can.

The gorgeous walking simulator Eidolon also uses fragmentary maps. While exploring its apocalyptic open world, you might be lucky enough to stumble on the occasional map to help you on your journey. Some are printed, others have evidently been hand-drawn by travellers who came before you and have moved on. The dearth of information effectively communicates your protagonist’s status as a lost wanderer, as well as the loss of access to knowledge in an apocalyptic, posthuman world; access which we often take for granted, both in and outside of games.

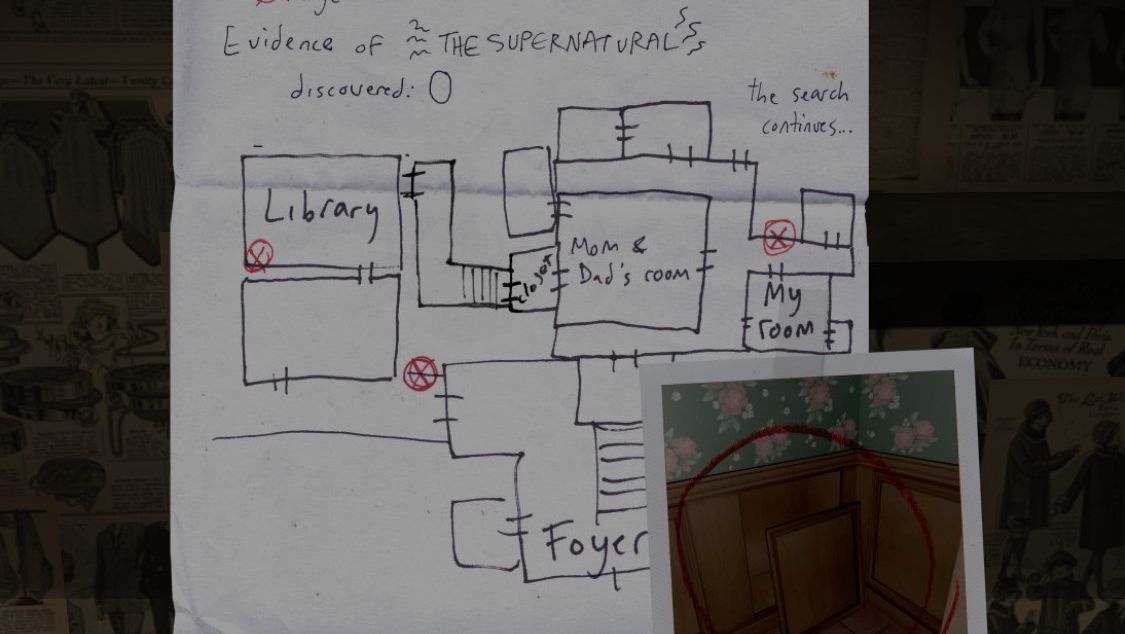

Other narrative games and walking sims feature makeshift maps with a more playful purpose. In Gone Home, we stumble on notes and diagrams drawn by Sam and Lonnie which document secret rooms and hiding spots around the house, as well as the not entirely serious hunt for the ghost of Uncle Oscar.

The Awesome Adventures of Captain Spirit takes the imagination of kids a step further. A map drawn by Chris shows the neighbourhood around his house but turns it into something fantastical. The tree house becomes a “flying fortress”, the pond behind the house a snake-infested “sea of darkness”, and the car in front of the garage a “space vessel” (which Chris uses to confront Captain Spirit’s arch-nemesis on Mars). Through clever use of maps, these games show how fanciful stories and fantasies grow around real places, especially in the minds of children.

Maps can easily move away from the concrete and literal. In Cultist Simulator, one of our goals on the road to otherworldly knowledge and power is to enter the Mansus, or the House of the Sun, through our dreams. The Mansus, a pyramid-like structure of portals and stairways, remains elusive and distant, as it is only represented through text and a heavily abstracted and symbolic map. In dreams, the Mansus is treated like an actual place that can be traversed, but the ascension to the top of the Mansus and the so-called Glory (a sun-like orb representing our goal) is also allegorical for the journey towards secret knowledge and enlightenment. It comes as no surprise that the map of the Mansus echoes historical esoteric images and alchemical symbolism.

The strange world of Planescape: Torment is similarly esoteric and dreamlike. Its world map is represented as irregular patches of sewn-together skin. The places we visit appear like tattoos. This makes sense when there’s a running theme of bodies inscribed with signs and meaning. The entire body of your character, the Nameless One, is covered in tattoos, signs and even writing. On another level, it also works as a metaphorical representation of the patchwork-like Planescape multiverse: its regions often appear both material and symbolic, and their positions relative to each other can be uncertain and tenuous – as if connected not by solid earth and stone, but aether and old string. The maps of Cultist Simulator and Planescape: Torment do their part to make their weird cosmologies intelligible to us, and this function is far more important than their potential use as tools for navigation or orientation.

Despite their differences, all these games share a fascination with the way maps colour our perception of space, and in turn their maps are shaped by our understanding of the world. They suggest worlds where maps are made by those with fragmented knowledge, cartographers who are biased, or who have limited points of view. Maps (especially world maps) tell us something meaningful about how a virtual world is seen by its inhabitants. They are the antidote to ubiquitous mini-maps and terrain covered in quest markers that only distract you from the world, instead of absorbing you in it. We can only hope that The Banner Saga and others will encourage more games to explore the uncharted potential of maps.