Hands On: Antichamber

Brainteaser

In the always imaginative word of indie gaming, it's ever-increasingly the case that finding out anything about a game before you play is to take away from the experience. But then you could argue the same is true of most things in life. Which is why I like to break into maternity wards and start telling babies all the spoilers I can think of. "Puberty sucks!" I will shout, as the angry midwives drag me backward from the room. "They lie to you about cell structure in GCSE biology!" I cry as I'm thrown through the doors. But here's the fascinating thing about Antichamber: even as the developer told me what the game was doing to mess with my brain while I was playing it, it still succeeded in messing with my brain.

Described as a psychological puzzle game, for once that doesn't mean that it tries to scare you a bit. It doesn't try to scare you at all. Instead it tries, and from what I've seen so far, succeeds at messing about with how you think, how you approach the game. So as I sit down next to creator Alexander Bruce to start playing, I'm faced with a large gap, and the instruction to JUMP. I jump, the gap is far too wide to cross, and I fall a very long way down a hole. Immediately the game has lied to me, broken the first rule of tutorials, and made it abundantly clear that it's not entirely on my side. Bruce grins, a little too knowingly for my liking.

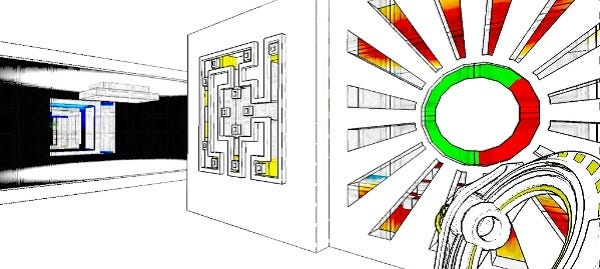

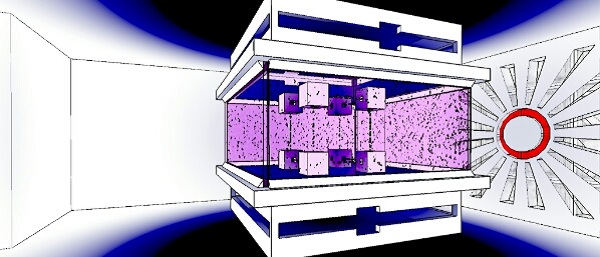

The engine, presenting itself as deceptively simple, draws minimalist white corridors, barely outlined in thin black, with simplistic icons on the walls that, when interacted with, display esoteric sentences that suggest hints. Not progressing in the direction I'd intended, it informs me, doesn't mean I haven't progressed. Fair point.

Then things start getting weird. Turning around to go back the way you came very rarely takes you back to the way you came. Turning four right angles is very unlikely to bring you back to the point you where you started. A passage that can't be accessed walking forward might be perfectly passable if you're walking backward. If you don't look at something, it's not necessarily there. And most of all, none of those illogical violations of reality are consistent with one another. Just because something just worked doesn't mean it will work again, and applying one understanding of the game's behaviour to another is unlikely to produce results. It's not so much lateral thinking as upside-down and back-to-front thinking.

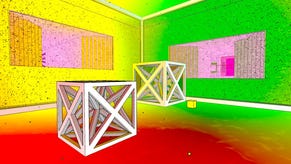

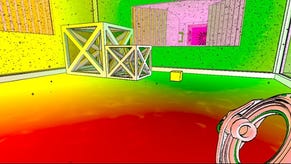

This is emulated by the objects the game presents you with, too. While the minimalist frames form the canvas for the game throughout what I've seen of the first quarter or so of the game, it's built upon by some really smart use of colour, brain-bending geometry, and some utterly remarkable features to gawp at. One room acted like an art gallery, filled with central cubes. Look through a side of the hollow cube and it contains some abstract piece, perhaps a flickering Escher-like shape, or maybe a more traditional sculptures. Then look through another side of the cube and the hollow space contains something completely different. Stand so you can see through two sides at once and you'll see the space containing two different things simultaneously. A corridor with a dead end may reveal a passage way if viewed through a glass window. A passage way that remains in place until you look through the window again. Space becomes meaningless, in a way that makes you wonder why the game's engine doesn't just refuse to work at the sheer pertinence of its unreality.

So I reach this point where I'm stuck. The game has just given me a gun-like device, that can pick up small blue cubes and fire them onto any surface in the game. I'm being asked to proceed down the corridor, as the game generally wants me to do, and I can't do it. Antichamber's creator, Alexander Bruce, explains to me, "This is the point where players get stuck. They can't figure out how to get past this puzzle. But the thing is, if someone were to walk up behind them and watch they'd know what to do. But you can't do it any more."

And I couldn't.

Feeling incredibly self concious at my being stuck at this point, I continued to fail, continued to try to manipulate the game, or be manipulated by the game, and go nowhere. And then I tried to imagine how this would look to someone who hadn't just spent ten minutes being messed with, and realised the solution. The mind-numbingly obvious solution that wouldn't even give me pause for thought in any other first-person puzzler.

That's why Antichamber is a psychological game.

Needing to let someone else have a go, I presse Escape to return to the chamber from which all previous puzzle areas can be reached (and of course a room that also messes with you at various points), and one of the room's walls is emblazoned with my stats, including the fact that I'd been playing for half an hour. I'd have guessed fifteen minutes. Bruce explained, in his permanently confident manner ("there isn't an indie award this game hasn't been nominated for" he explained to me matter-of-factly at one point), that this was very normal. People have spent hours playing it, he said, without realising they were late for appointments.

It seems his confidence is well-placed, and while it's always tempting to find room to disagree with someone so keen to tell you just how good his game is (the front page of the game's website doesn't tell you information about the game - it boasts its award nominations, and then extensively lists the praise the game has received), the thing is, I think he's right. This is fascinating.