The Flare Path: Poppies and Poppycock

WW1 deserves better than 11-11 Memories Retold

Let's call them “poppies”, the eye-catching, ephemeral moments in 11-11 Memories Retold when you glimpse the brave, powerful game it isn't but could have been. One of the tallest poppies grows from shell-scarified sod about halfway through this big budget, big name 2018 adventure game. In the skin of Kurt, one of the two protagonists, you find yourself in a sprawling German war cemetery, searching for a particular grave. Accustomed by now to insultingly easy puzzles, you walk to the nearest makeshift cross, and, when a “this is clickable” icon appears, dab the E key expectantly. No luck - a stranger's name and unit blazons the screen. You move to the next cross and press E again. The name of another unknown individual appears. After the third or fourth failure, with mounting frustration you pause and survey the sea of crucifixes. A multifaceted thought crosses your mind - “I'm going to be here all day.”

You're not, of course - helpful gravediggers see to that - but I tip my hat to Aardman Animations and DigixArt for implying it. 11-11's problem is that it's usually too busy unspooling a preposterous plot and putting dull words in the mouths of dull characters to create conditions conducive to reflection and empathy. At some point in the design process someone with influence decided that the WWI experienced by millions of ordinary soldiers - millions of ordinary soldiers like my great-grandfather - the WWI you can read about in memoirs and poetry, wasn't sufficiently exciting or memorable. What was needed were plot twists so ludicrous they'd make The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe look like Nordic noir.

I can just about cope with the presence of Kurt and Harry's pets, a tame cat and pigeon that you sometimes inhabit in order to solve puzzles. This is an Aardman project after all. What I struggle with is that these pets are occasionally given the role of supernatural fate shapers and allowed to meddle with history in a truly outrageous manner.

Picture the scene (or skip to the next paragraph if you want to avoid spoilers). It's the eve of the Battle of Passchendaele. Harry, a young Canadian working as an unofficial war photographer, attempts, as you do, to lighten the mood of his angry boss, Major Barrett, by using his pet pigeon to retrieve some important battle plans from the Major's tent. Instead of bringing the papers back, the bird inexplicably decides to fly across no man's land and give them to a German soldier (Kurt, a German who joined up in order to locate his MIA son) that Harry had encountered briefly earlier in the war. Kurt hands the papers to his superiors. The British plans are secret no longer! Barrett blows his top while you shake your head and sigh like a bullet-riddled observation balloon.

In a Chicken Run-style comedy or a fantasy in the Dark Materials vein, a literal flight of fancy like this might have slipped by unnoticed, but in the magic-free and almost entirely joke-free 11-11, a game seemingly keen to explain WW1 to a generation of gamers who may be largely ignorant of it, it jars horribly.

The game's silliest event occurs very near the finish and can't be described without spoilerage (skip to the next paragraph if you'd rather not hear about it). Harry, by then a prisoner of war, is in Germany staying with Kurt's wife and child at their idyllic farm. The war is obviously about to end so, naturally, he decides to fly hundreds of miles across a flak-scourged, fighter-patrolled warzone in a homemade balloon in order to 'escape' and/or find Kurt. Amazingly, the balloon crash-lands a few hundred metres away from the spot where Kurt happens, at that precise moment, to be facing his nemesis. Result? A game that could and should have left you feeling bruised, tearful, dazed and haunted instead leaves you feeling like a pillock for investing emotion in its cockamamy narrative.

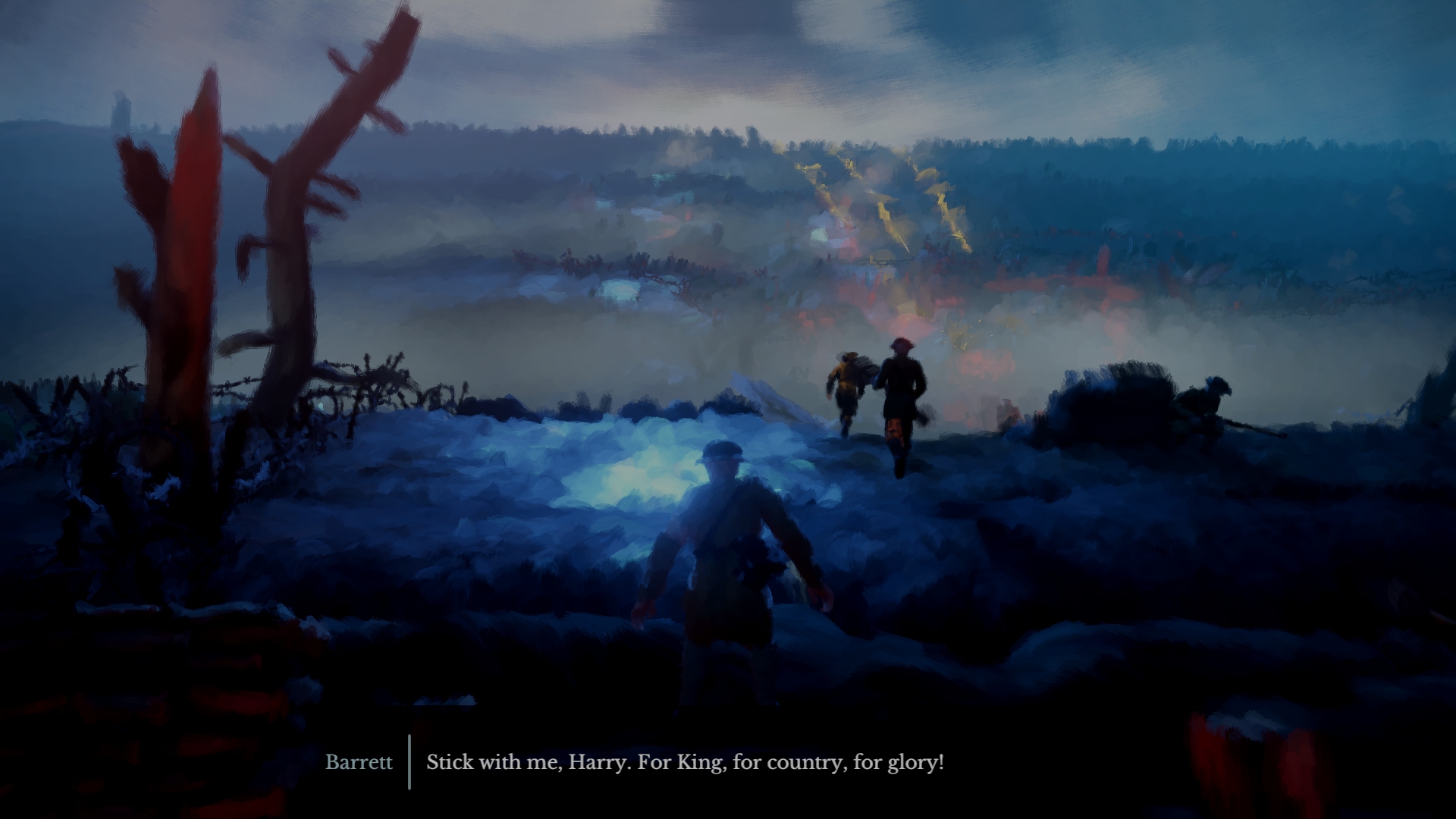

Still, those scattered poppies I mentioned earlier mean the six hours I spent with 11-11 don't feel totally wasted. There were a couple of uncommonly atmospheric attack sequences that hint at what the game could have achieved had it been pushed in a different direction.

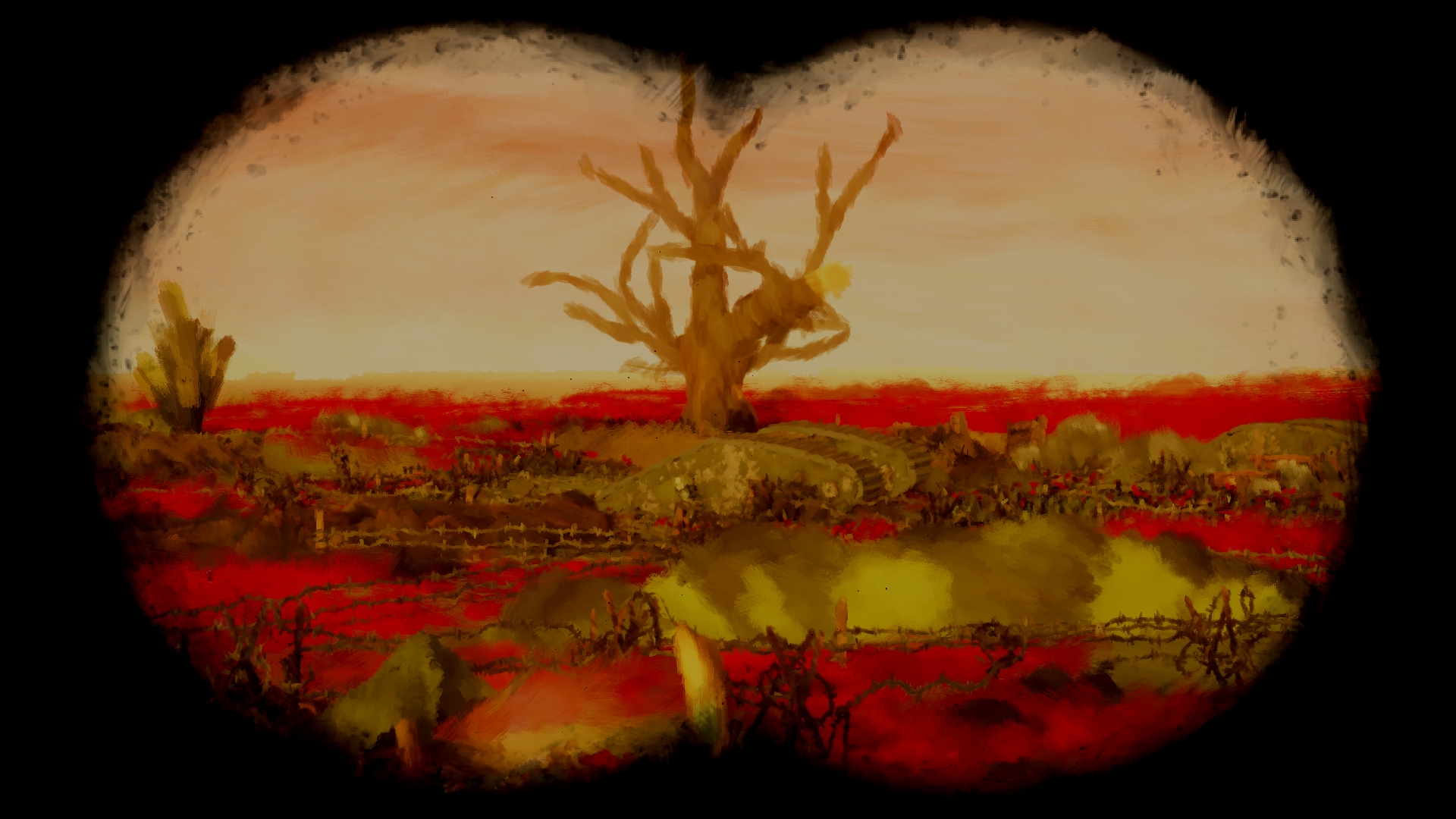

The painterly filter that's constantly smudging outlines and disguising detail (scenes gently shimmer like breeze-ruffled crater pool reflections) gives battlefields and gasmasked soldiers a strikingly nightmarish look. A dev nervous about depicting the true visual horror of trench warfare could have used this natty automatic expressionism to show-but-not-show the kind of gory realities gamemakers generally avoid. Aardman and Digixart squander the opportunity, sadly. You see fuzzy corpses during battles but all are undamaged... fresh... inoffensive.

I almost abandoned 11-11 in disgust the first time Harry experienced combat. Difficulty wasn't the issue - darting from convenient cover spot to convenient cover spot while following Major Barrett across no man's land wasn't especially tricky - it was how the game reacted when I mistimed a run and was felled by a flurry of lead, that exasperated me. Without so much as a moody fade-to-black, I was teleported back to the previous safe place and told, in effect, to try again. Nothing says “WWI warfare” like instant infinite respawns.

In addition to running the gauntlet from time to time, the two friends are also expected to push the odd crate and cart, complete some simple fetch-and-carry chores, drag wounded comrades to safety, fix electrical equipment/radios (Kurt), take photos (Harry), listen for subterranean enemy activity with a stethoscope and write the occasional letter home. The latter pair of activities draw on the subject matter better than most. Too often the easily surmounted obstacles strewn in your path seem rooted in adventure game lore rather than 1914-18 history. “Find cat”, “Collect three pieces of fabric for balloon building”, “Steal hip flask so Jas can repair his guitar”... such tasks tell the player next to nothing about what it was like to participate in the Great War, and aren't particularly entertaining to boot. Like Kurt and Harry themselves, they have to go down as missed opportunities.

Harry, the callow Canadian youth you spend half your time directing, has the personality of a disposable razor despite Elijah Wood's best efforts to breathe life into his predictable musings. After spending around three hours in his company, all I can really tell you about him is that he worked in a photographer's shop before the war and fancies the owner's daughter; he's rather attached to a nameless pigeon, and, for all intents and purposes, is fearless. The empty vessel approach might have worked if we'd been given the chance to gradually add liquid via meaningful moral choices, but there are no such choices. If his extraordinary war experiences change him, then the change is all but undetectable. He's essentially the same big-hearted idiot at the start of the game, as he is at the end.

Older and moodier, Kurt is a more promising character. His search for his missing son produces the game's most moving moments. The cemetery scene, a dream sequence set in an imaginary no man's land, and a bit where he finds himself distributing gas masks in the midst of a gas attack almost justify the entrance fee on their own. But in addition to being a devoted father and an ex-zeppelin engineer, Kurt is also an unlikely thief (he's happy to steal items from his neighbours minutes after commiserating with them about their KIA sons) and an improbably gifted commando (he somehow slips through enemy lines at the end of the game) so it can be difficult to take him seriously too.

Thankfully, the shallow characters and preposterous-in-places plot do at least service a responsible message. 11-11's sleeve-worn heart is in roughly the right place. Aardman and DigixArt clearly set out to show that the conscripted soldiers of both sides had much in common, and would, given half a chance, make friends rather than fight. War's ability to dehumanise is touched upon, the misery of trench life rammed home by a vast supporting cast of incidental grunts whose primary purpose is to deliver unhappy utterances like “I miss my wife”, “Curse this war” and “We're going to die here”. Yes, I'd like to have seen subjects like wounds, shell-shock, bayonets, and mud tackled with more directness, more honesty, but if I had sprogs, I'd much rather they learned of the monster that killed their great-great-grandfather through the flawed, far-fetched 11-11 Memories Retold than through a blasé combat playground like Battlefield 1.

11-11 Memories Retold is £10 on Steam until May 6 when it reverts to its usual price of £20.

* * *