Gone Home: A Tale Of Two Dads

So-called lives

Entirely understandably, the bulk of the deservedly rapturous reception to Gone Home has focused on its unseen narrator Sam, a teenage girl who gradually and powerfully documents her timeless emotional and social trials. While it was certainly the dénouement of Sam's tale that prompted open tears from me and that will, I sincerely hope, see this game reach a wide audience of human beings, there are (at least) three other stories in this short game, taking more of a background role and enjoying no narrator, or indeed any kind of explicit call for attention.

I found a little extra personal resonance in a particular one of these, and it's that which prompts me to interrupt my sabbatical from work and post about it now. Be warned that here be both spoilers and navel-gazing.

There's a reason I can't entirely connect with Sam, much as her story moved me deeply, and it isn't because she's female, or gay, or American, or a videogame character. It's because she's cool. I was a similar age at the same time, but I was not cool. Perhaps she didn't consider herself cool either, but she was: outsider cool. Freak cool, not geek introversion. Zines and basement gigs and rebel clothing choices were just incomprehensible whispers from another world to me. I didn't even hear the term riot grrl until several years after the event. Nirvana (until a few years later, when my brain and ears finally matured) just sounded like noise. I didn't have to worry about the effect of major lifestyle choices on my social life, because I didn't really have a social life to lose. The dual oppressions of being a nerdy waif at a sports-focused, essentially Conservative school and an upbringing that prided discipline and academic achievement far above anything so indulgent as happiness or self-confidence meant finding myself, let alone rebelling against normality, was simply an impossibility.

What I did was to lose myself in turgid licensed sci-fi novels, X-Men comics and whatever PC games I managed to pirate from richer kids (who were not my friends but for some reason accepted me on that one basis). I listened to Meat Loaf and Bon Jovi, though I just about discovered the glossiest side of Britpop before I was a lost cause. I didn't go to cool gigs or dye my hair or distribute photocopied words and pictures created from pure passion and personality. I share(d) a certain loneliness with Sam, but really the most concrete comparison is that we both loved the X-Files.

My So Called Life beats quietly through Gone Home's veins, but I was no Angela. I was Brian. Not even Brian, if I'm honest. And so, playing Gone Home, it's the less prominent sad sack I identify with the most. Someone who's not a hero, someone whose voice is never heard, someone who feels rejected by life but who hasn't acknowledged the role he plays in that dispossession. Perhaps because the real cause comes from a previous generation.

Terry, father of Sam and her sister Katie, is a writer. A failed writer, whose grand ambitions run aground and who has recently found himself doing the literary equivalent of turning tricks down on the docks. He's writing technical, bullshit-strewn reviews of hi-fi equipment, for a magazine and an audience that believes life is meaningfully improved by minor differences in picture quality or mid-range tones. He has to sound enthusiastic and authorative about the Emperor's new clothes, time and again. Were he still doing that in 2013, he'd be pretending a £100 HDMI cable can do something a £1 one cannot. He'd be called out here, no doubt.

As it is/was in 1995, we soon discover that he couldn't keep up this joyless, mendacious facade for long, started turning out awful copy, and quickly fell out of favour with his commissioning editor. It's not entirely comparable, but I certainly had more than a few mental wobbles when the outcome of my journalism post-grad degree turned out to be reviewing fucking printers for a computing magazine. I know how he felt.

Meanwhile, his sci-fi series about JFK and time travel has resolutely failed to sell, sequels have been refused and no amount of motivational post-it notes he leaves for himself can keep him from the worrying number of bottles and shot glasses that litter his rooms in the enormous house that is Gone Home's setting.

None of this is told to us. It's just there to discover, if we so wish, in typewritten, half-finished reviews, scrawled notes, decreasingly cheerful letters from his editor, and a jarringly miserable mini-bar strewn with empties. Piece it all together, if your mind's eye, and a very clear picture of Terry forms. He never speaks, he's never seen outside of an oddly mutant-faced family portrait, and I don't believe we read anything that's a direct admission of what he feels - it's all in the reviews, the books, the stiff, dismissive responses to the reviews and books, and all those empty bottles and glasses. But I knew, I know, that Terry was completely, utterly lost.

That isn't me now, not really, though I inevitably nurse any number of unfilled artistic aspirations, but oddly it did evoke me then, even though me then was barely half Terry's age then. No-one seemed to take him seriously, he seemed to lack a clear idea of what to do with himself, he turned inwards rather than sought to improve his life. He inadvertently drove others away because of it. I wonder what reasons Katie would give for her long time abroad, if she was entirely honest about it.

Sad sack. I won't be surprised if plenty of Gone Home players - and, though we don't hear them say as much, the rest of Gone Home's unseen cast - consider him pathetic. Clearly, he fails Sam in her hour of need, and despite social conventions being a little different back then, I'm not convinced it was homophobia or even simple discomfort that did it. It was being too self-pitying to be capable of supporting someone else in their emotional struggle. It seems, or is implied by assorted, restrained notes and calendar entries, that his misery, or his lack of thereness, drove his wife to seek ultimately unrequited comfort from a hunky colleague. He suffered, I think, the kind of hopelessness that pushes people away rather than encourages them to come to your side, and I recognised it all too well.

Later in the game, I also recognised the root of it.

God, I hope my dad never reads this.

In the impossibly gigantic basement that runs underneath Sam, Terry et al's impossibly gigantic home, there's a letter. It's not a letter that need be read in order to enable progress or advance the core plot. It's easily missed, as many things in Gone Home are. It's in the dark, requiring you to find and activate a light in order to see it, as almost everything in Gone Home does.

It's from Terry's father. It's about Terry's first book. It's superficially a congratulation. It's realistically a knife in the ribs from a man who doesn't care about his son's feelings or personality, only how his son's achievements reflect on him. I forget what Terry's father's job is stated as, though I seem to recall his name had some professorial prefix. Certainly, his style of writing - stuffy, cheerless, officious - reflects this. It reads like a note from a headmaster to a barely-remembered former student, not a father to his son. It opens with recognition that Terry has been published, then without warmth turns to admonition for perceived stereotypes and lacklustre turns of phrase in what does, admittedly, sound like a cheap and nasty thriller. Sucker punch right to my limp stomach.

Terry probably knows, on some level, that it's cheap and nasty, and perhaps even deliberately targeted a certain audience. That doesn't for one second justify his father, the person who should be the most important man in his life, pointing this out, criticising him for it. Making him feel small, worthless, nothing.

In that one letter, Terry's entire personality and every mistake he ever made - and quite clearly continued to make - was explained. I winced, and I remembered. My relationship with my father isn't like that now, isn't hung around my achievements or lack thereof, but it was, and it still hurts a little, no matter how far we've come from it, no matter that my dad now entirely accepts and respects that I've somehow made a career out of my nerdy childhood interests rather than the maths and mechanics he pushed me towards. He was never as stuffy or as cold as Terry's mirthless, aloof father seems, but put it this way - he once give me a maths textbook as a birthday present, in response to falling grades. I felt Terry's agony, felt the rejection he suffered, felt his struggle to anchor himself in life, felt his struggle for approval. I felt the contempt of his father, and it hurt.

There's a suggestion, near the end of the game, that Terry and his ridiculous novels are redeemed, rediscovered. We don't see the outcome, but we do see a rare letter directly from Terry, positively brimming with joy and disbelief that a new publisher wants to bring his books back to market. This part of Terry's story perhaps didn't resonate as well for me - it seemed a little too cute and unlikely, and for that reason I chose to believe that, ultimately, his books failed to sell for a second time, and his sequel proposal was ultimately rejected once again.

I also chose to believe that his cold, cruel father died before the two of them ever experienced any closeness, that Terry would be forever left feeling unappreciated, unloved, unsuccessful, no matter what he went on to do. That way, I could not be Terry - I could be better than Terry after all. Go Home, with its implications, its off-camera characters and its clear picture built only from words and shadows, gave me the freedom to finish Terry's story that way. While Sam's story is essentially told outright by the end of the game, only brief, uncommented upon components of Terry's story are ever given, leaving me to piece them together and experience my own reaction to them.

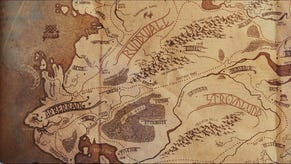

Poor Terry. As the damning image above shows, he made witless attempts to help his daughter, but I'm not sure he'll ever experience the euphoria, the self-discovery and the freedom that Sam did. I'm worried he's well on the road to becoming like his father - seeing family members as problems in need of solutions, rather than unique human beings with all their infinitely complex internal struggles. I hope I've escaped being Terry. But I can't guarantee it. I hope I don't do what Terry's dad did to him to my child. I hope I can see past myself enough to be be able to help her when she needs help.

Good luck, Terry. I hope you manage to find yourself.

Addendum - ah, it's been brought to my attention that I didn't pick up on a further, yet more important and tragic implication about Terry's past and its ongoing effects upon him. There's a reason he's obsessed with the year 1963, and why he apparently stopped visiting his uncle Oscar in this sad house in that very same year. Puts things in a whole new, even more tragic light.