How Risk Of Rain Increases Difficulty Over Time

How time doth waste you

This is The Mechanic, where Alex Wiltshire invites a developer to help him put their game up on blocks and take a wrench to hack out its best feature, just to see how it works.

The start of a game of Risk of Rain [official site] is quiet. Your small pixel character stands in a vast alien landscape, in which somewhere you’ll find a teleporter that will take you to the next level. The end of a game of Risk of Rain is mayhem, the land swarming with monsters that you couldn’t survive.

And throughout lies constant stress and pressure. You’re ever aware of a meter in the top right corner of the screen that ticks upwards. Every five minutes, a bell chimes and the difficulty changes: from Very Easy, to Easy, to Medium, and further. The constantly respawning monsters come ever thicker and harder, inexorably escalating towards unmanageable chaos. You must never stand still and must never relent, because with every second your own downfall nears. All because of:

THE MECHANIC: Time = difficulty

That’s Hopoo Games’ feature list term for the system that shapes Risk of Rain’s distinctive take on the action Rogue-like. “The longer you play, the harder the game gets. Keeping a sense of urgency keeps the game exciting!” Or stressful. Because if you’re not collecting XP or items and powerups, or if you’re not progressing to the next level by triggering the teleporter, you’re making everything harder for yourself. Richard II had it right: “I wasted time and now doth time waste me”.

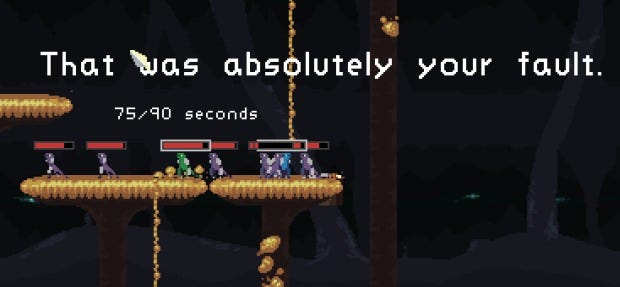

Time = difficulty is also there to serve a specific purpose. It works a little like the action equivalent of the hunger mechanic in a traditional Rogue-like, but Risk of Rain has extra need for it. Unlike most Rogue-likes, its levels endlessly spawn monsters until you trigger the teleporter and survive the resulting 90 seconds of waves of enemies. Without time = difficulty, its levels would be endless sources of XP. And because levels are speckled with finite numbers of items, which transform your powers, XP isn’t enough on its own to face the rising difficulty level.

So Risk of Rain confronts you with a choice. “There are two extremes. One where you run right to the teleport and turn it on and then go right in. That’s how I like to play,” says artist and programmer Duncan Drummond. “But a lot of people have success where they clear the entire map and open all the chests.” The game is balanced so that both options are viable, give and take.

And give and take is very much the way Risk of Rain works. As much as the difficulty meter moves through five-minute increments towards its highest setting, HAHAHAHA, behind the scenes it’s actually increasing in one-minute increments. That’s to avoid facing a jarring step-change in monster-toughness and damage every five minutes. With more gradual increments, the challenge is smoother. On the other hand, as you gain items, you get sudden boosts in power, lending the game a rhythm of power and weakness as you surge ahead of the monsters, and then find them catching up with and surpassing you again.

So what does the rising difficulty actually do? Every minute, the game raises a value that represents the monsters’ net power value. This value then scales monster health semi-exponentially, and scales their damage output semi-logarithmically. The difference in scaling reflects the different ways your character increases in power. Items mainly affect your damage output, and the way they stack and complement each other means it tends to rise exponentially over time, so the monsters’ health rises to match.

But your health gains are mainly caused by levelling up. Because you need increasing amounts of XP as you level higher, your health gains slow down over time in a logarithmic progression. Also increasing monster damage logarithmically helps to avoid late-game situations where you can be doing huge damage but be susceptible to one-hit deaths. “We weren’t big fans of that kind of gameplay,” says Drummond. But late in development, he and partner and lead designer Paul Morse added items that raise health or reduce damage by a percentage, helping to make players’ health curves a little more linear.

The result is a system that’s governed by time on one hand, and on the other by you striving to develop your character. But the asymmetric way the monsters and you develop leaves some fantastic spaces during a game where the challenge suddenly drops, making you feel powerful, and suddenly rises, making you panic.

This wasn’t exactly the plan at the beginning of development, when Drummond and Morse had just started their sophomore year at University of Washington. Then, Risk of Rain was going to be a kind of base-defence game, in which you had to protect your crashed ship from monsters, and the difficulty rose with distance away from it. But the idea didn’t work. “We realised players wouldn’t have motivation to go far,” says Drummond, and so the difficulty = time system came in as a way of keeping players moving and exploring.

They’d also planned at this stage that the speed at which you killed monsters would adapt the scaling. “But from a design point, it took out your highs and lows, and I think that’s what’s really interesting about the game: when you feel you’ve broken it, for a little bit at least. Or if you feel absolutely overwhelmed,” says Drummond. “If we did the scaling with you correctly, I think it’d make every round feel the same.”

“Monsters would scale to you, so it wouldn’t be that rewarding,” adds Morse. The vast bosses that appear during the teleport countdown, however, do scale to you, hitting you for a percentage of your health, and they’re designed with one attack that reduces your health to one, and another that makes them invincible for a period. “So they feel kind of scary no matter how strong you are,” says Morse.

The difficulty system doesn’t only affect monster power. It also raises their numbers. Spawning is driven by an AI that is given a certain number of points a second, at a rate that’s scaled to the difficulty level. Each monster costs a certain number of points; a lizard is five, and a boss is 800 points. Every two to 15 seconds, the AI attempts to buy monsters. If it, say, has 40 points, it might try to spawn as many lizards as it can, which would be eight, except if the AI can spawn five of a single monster, it will instead spawn a super version of it.

This ‘affixed’ monster is a lot harder to kill but is more rewarding, and also gives combat an extra level of dynamism. Yet, as it happens, the whole affix system only came about because of the limitations of GameMaker, in which Risk of Rain is built. As the difficulty rose and the game started spawning more and more monsters, performance would drop. Affixes essentially take five monsters and combine them into the computer performance of a single monster. “I don’t know if it was lucky, but it’s a merge of game functionality and game design,” says Drummond.

There are 110 items in Risk of Rain. There are many types of monster, two complex systems governing their power and quantity, and all the different player classes. That’s a lot to balance, but Hopoo pushed the main balancing factor towards monster quantity, knowing that raising their health as a means of making them balance would risk creating boring bullet sponges.

Item balancing, though? “You can definitely break the game if you accrue a specific set of items,” says Drummond. “You’ll be invincible or kill everything on-screen without moving. But I think that’s perfectly fine for a singleplayer game. That’s the real fun part.” The game deals items semi-randomly to you – chests and shrines dole out single random items and sometimes you have a choice of three random ones – which mitigates some of the potential for becoming overpowered in the early game.

But knowing the value of items is still down to player experience, and for those who have played Risk of Rain a lot, the most valuable items are those that lend mobility. That’s because extra jumps and speed negotiate with the game’s real economy: time. As Richard II probably would’ve added if he hadn’t been murdered, waste less time, and time doth waste you less, too.