Wot I Think - Torment: Tides Of Numenera (for Planescape veterans)

For those familiar with torment

You know Planescape: Torment well, and chose to hear whether Torment: Tides of Numenera will betray your trust or not rather than to have its nature defined first.

Please note that certain key elements of the game are skipped over here, which is because they are covered in more detail in the Torment newcomers review here. I did not wish to repeat myself unduly in an already long article. If you are a Planescape veteran, I do encourage reading both pieces. After all, you rather like reading, don't you?

We expect certain things of a game with 'Torment' in the title - expectations that have mounted rather than faded over the years.

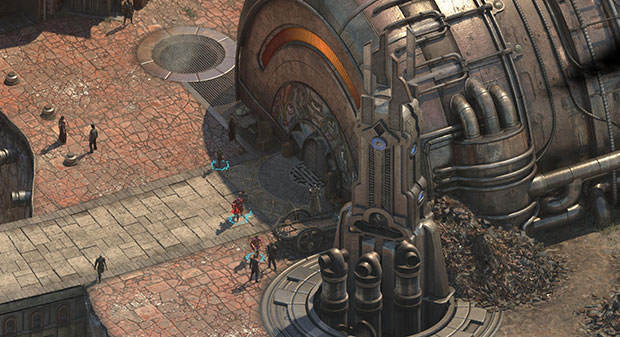

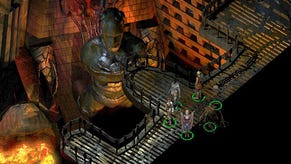

We expect striking, sinister architecture and weird creatures of uncertain intent.

We expect extensive excavation of moral grey areas.

We expect decisions to agonise over.

We expect to barely raise a fist in anger, unless it is our specific choice to.

We expect words, not spectacle, to do the heaviest lifting.

We expect a mystery that unfurls into existential questioning rather than neat resolution.

We expect to feel that we have barely scratched the surface of possibility, and to find that our journey is fascinatingly, unpredictably different when we start it over.

We expect to end the tale with mingled satisfaction and despair.

We expect Adahn.

We expect what, more or less, Torment: Tides of Numenera gives us.

By which I mean: relax, it's good news.

I should say first that Numenera feels more constructed than did Planescape. It is very clearly created to give fans exactly what they demand. Because of this there is a palpable sense, at times, that its creators carefully reverse-engineered its revered 1999 predecessor, perhaps even working from an inviolable set of commandments about what makes a Torment game a Torment game.

Sometimes this does robe Numenera in a certain scent of artificiality, where by contrast Planescape felt organic, this shiny new mind unexpectedly breaking through the confines of the roleplaying game structures of the time. Only a little, though. Though once in a while there's a slight clunk as it blatantly reaches to hit expected beats, in the main Numenera is exactly the game it needed to be.

Steam tells me one playthrough took me 36 hours, but at least some of those were spent reloading savegames to explore alternative outcomes for the sake of this review. If you plan to play this as a conversation- rather than action-led character, as I did, teasing out every thread you can find, as I did, expect to end up with something similar.

However, I am relatively certain that one could blow through the campaign in a third of that time if side-quests were neglected and violence favoured. I recommend against this, not from a pacifistic point of view, but because Numenera is such a deft cat's cradle, with even some of its most seemingly irrelevant fetch quests and favours containing ties to the bigger picture. In some cases this means more insight into how this place works and who your character may or may not be; in others there are moving or harrowing unexpected consequences that only reveal themselves in the long-term.

It is those consequences, more so than the central story (or, more specifically, it is those consequeces' ties to the central story) that achieve the most emotional clout. Take your time here. Explore everything. Do nothing thoughtlessly. Know that your actions will be rewarded, or punished as the case may be, and anticipate that more than you do the conclusion per se. When the final act arrives, it does so somewhat abruptly and introduced by an oddly weak twist - my chief disappointment with the storytelling.

There is a faint sense that, perhaps, Numenera is one area shorter than it needs be - not in terms of length, but in terms of flow. I do not know if something was left on the cutting room floor or if it is simply a wobble in execution, but I did feel suddenly railroaded into climactic events before certain strands of the story and world (both deeply intertwined) had seemed fully teased out. This is not to say the absolute conclusion is weak - quite the opposite in fact, due to its remarkably thoughtful links to your choices across the course of the game, and it has scope to play out significantly differently because of that - but rather that the moment of movement into the final phase is a little jarring.

The other disappointment (I'll move back to praise shortly, fear not) for me was the central character. It is here that I proved most unable to push Planescape memories and attendant expectations aside. Its protagonist, The Nameless One, was immediately memorable, both in his forlorn yet determined nature and his half-monstrous, half-tragic appearance. He was walking sadness with a something deeply dangerous bubbling just underneath his scarred, grey-blue hide, and this concept of his being the risen dead, immortal despite his better wishes, spoke to true weirdness. He himself made it clear that we had side-stepped into a different reality of roleplaying games.

Numenera's The Last Castoff, by contrast, is rather a more conventional figure, despite having, if anything, a more thorough and extensive backstory with profound and strange links to almost every aspect of the world they find themselves in. Though their story spirals off into singular places, in appearance, essence and even treatment by others they cleave closer to the sort of character one might find in a Dragon Age or, to be carefully specific about how this shakes out, Baldur's Gate II.

My suspicion here is that more thought has been put into the Last Castoff's story than has his or her personality. Clearly, a keystone of a Torment game is that the player can impress their own beliefs and attitudes into the tabula rasa that is their character, but even so - The Nameless One was very much The Nameless One. The Last Castoff could be anyone.

This story-over-personality issue is particularly apparent during Numenera's first and weakest couple of hours, which suffer from an overload of both lore and terminology (specifically, rules from the pen and paper Numenera RPG setting this game is based upon). My heart sank as I felt as though any possible points of connection with this world were being drowned out by someone's uncensored fiction and presumed knowledge about an external game from a different medium. There were walls everywhere I turned, and I felt exhausted by the huge array of new NPCs waiting to gabble lore at me in every new area or building I entered.

My fear was that the whole game would be like this - that the successful Kickstarter had given the writers a blank cheque to do anything they wanted, unfiltered, uncensored, unedited, and it had resulted in wearying drone of Ideas.

Fortunately, this was resolved by a combination of Torment narrowing its focus to characters rather than high concepts and simple perseverance enabling me to reach through the initial babble and find the threads that mattered. Those threads are long, enmeshed with the very essence of Torment's setting, and spin off in unexpected directions, regularly causing me to question my own actions even though I largely stuck to a philanthropic, empathetic path.

Depending on the choices you make - some moral, some a matter of effort and determination - seemingly inconsequential events explode into later significance. Though the Last Castoff themselves never touched or broke my heart, a couple of the characters they came into contact with did. I can say no more, you understand. Against this, other characters - by which I mean possible party members - did feel as though they were short story first, personality second, and I left them benched unless a specific situation seemed to call for them.

A couple of companions here (and one in particular, but I shall write about them separately, later) are fit for a place in the halls of honour, but others failed to be as memorable as the cast of grotesques and unfortunates in Planescape: Torment. Everyone I met seemed to be, to all intents and purposes, a human with a tragic backstory, not the alien oddities or malevolent powderkegs of Planescape. There is no Ignus here and, most noticeably, no Morte either.

Two things here, mind you. One is that I was younger, more impressionable, more patient, more willing to be overcome when I played Torment. Characters that might seem less compelling now, after these tired eyes have seen, heard and read so much, were fresh and exciting then. The other is that, of course, I cannot say with any certainty that I have not missed something - someone. I look forwards to secrets I had not even guessed at being revealed.

When I hear about those secrets, they will doubtless turn out to be new vertebrae along Numenera's long and twisting backbone, not diversions off to one side. The dawning realisation, as I played, of how precise this initially random-seeming weave was, is why I am in awe of what has been accomplished here.

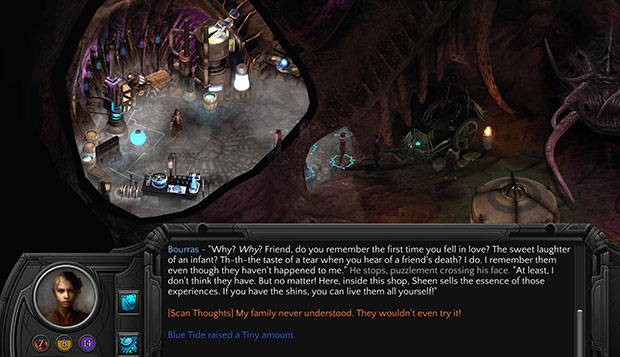

The central reason for Tides of Numenera's being is a riposte to RPG convention - that this should be a game where story, and exploration of what that story means, is of infinitely greater importance than spectacle and action. Not for this the lurid sex scene, the legendary weapon or the explosive magical lightshow. Plenty of combat (turn-based and party-based) is available if you so wish, though I found it to be rather functional and with far less fascinating consequences than talking my way out of or into trouble.

That is because Torments spends the bulk of its energies instead on connection and on meaning. I am avoiding details of the story, for that should be discovered for yourself, but suffice it to say there are many commonalities with the themes explored by Planescape. However, the question is not 'what can change the nature of a man?' but rather 'what can change the nature of a world?'

The answer, of course, is 'you.'

This is an uncommonly elaborate act of videogame storytelling. At times, it leans very close to interactive fiction, while at others it carefully explores the talk down or fight formula that characterises many latter-day RPGs. I engaged in very few battles, always preferring to find a peaceable solution - if anything, Numenera is a little too built for this, and it's too easy to become a god of conversation. By the midpoint of the game, it was a foregone conclusion that I could succeed in any conversational gambit I chose - the question was of the consequence of that choice, not whether I could pull it off in the first place. Planescape felt like a constant gamble by contrast.

I suppose what I'm saying is that pouring all my level-up points into cerebral skills never felt like a compromise. I am broadly happy with this, because that is the game I wanted to play, and I appreciate how finely Numenera is balanced to be a game of talking and reading rather than necessarily one of violence, but I would have felt more pull to immediately play it again had there been a more palpable sense that I had missed out on things by not choosing aggression. I may be wrong there - there may be whole strands as yet unexplored. It did not feel like it, but felt instead that I would be shutting down rather than opening up possibilities. I may be wrong.

Let us talk, finally, of writing and of presentation. It is a well-written game, yes - often, the quality of the words, the play of their language, the ludicrously careful interplay of their themes, filled me with both awe and envy. Other times, it all seemed flabby, too caught up in showing off ideas and colour to find the truth of its message and the heart of its characters. While once I believed that there was no greater accomplishment for a game than to contain a novel's worth of words, these days I respect the editor's knife almost more than I do the writer's pen. I would prefer Numenera shorter rather than longer.

(He says, guiltily eyeing the 'word count: 1871' notification below this, and conscious that he has three other sections of this 'review' still to write).

Nonetheless, this is a triumphant achievement in (near)mainstream games writing, and of taking fantasy themes and transforming them into the meaningfully human rather than the merely mythic. A little more small-c conservatism would have been a boon, and it takes a little too long to reach its focus, but when it does it puts most everything else in the shade.

It is frequently a beautiful game too, as should be expected. Technologically, it's a few years behind the RPG pack, but I'll take simplistic character models and 2D backdrops any day when they have this degree of fidelity. Though mostly static, the environments are huge and lavish, filled with beauty, oddity and sometimes gruesomeness. My chief excitement on progressing to a new section of the game is about what sights will sprawl across my screen. Once in a while, it even achieves relatively spectacular setpiece.

There is, throughout, a slight air of artificiality to Torment: Tides of Numenera. It has been made to please a specific crowd, and sometimes that shows; sometimes that comes at the expense of what matters most. This is outweighed entirely by the scale of this accomplishment. Torment is the weird, wordy, wise and wicked roleplaying game we've so desired during these long years of heightened spectacle. Not a total triumph, no, but close enough.

Our expectations have been met.

Torment: Tides of Numenera is released today for Windows, Mac and Linux, via Steam, GOG or direct from the devs.