How Total War: Warhammer's Mortal Empires engineers a world of unending war

How to build an empire

This is The Mechanic, where Alex Wiltshire invites developers to discuss the difficult journeys they underwent to make the best bits of their games. This time, Total War: Warhammer’s Mortal Empires campaign [official site].

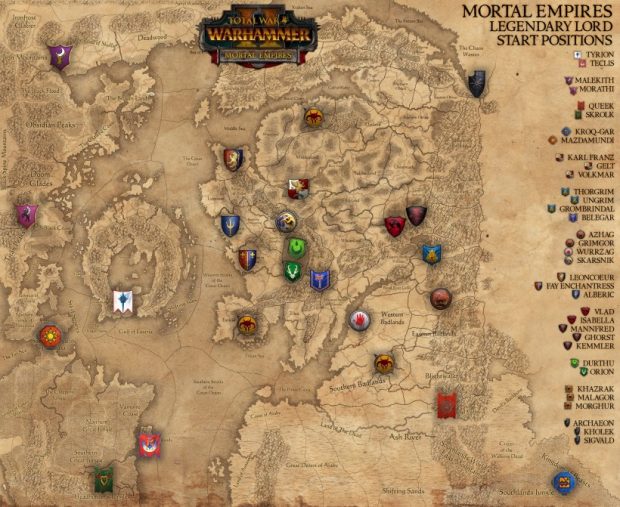

Mortal Empires is the logical conclusion of Total War: Warhammer. It asks this: what happens if all the races, factions, legendary lords and terrain of both Total War: Warhammer and its sequel were folded together into a single giant campaign? The answer was released in October as a free addition to owners of the two games, and it is, as game director Ian Roxborough tells me, “By far the biggest, most content-rich campaign that we’ve ever done in Total War.”

But how do you make games that are designed to be played both in discrete and distinctive smaller chunks, and also in huge and unified ones? How do you balance Warhammer’s strongly asymmetric races against each other while continually adding more? And how do you make a game as big as Mortal Empires comprehensible and playable at all?

The Old World of the Empire, Vampires, Greenskins and Dwarfs, and the New World of the Lizardmen, Skaven, High and Dark Elves, were each designed to push their native races into carefully orchestrated conflict. Whether Greenskins against Dwarfs, Skaven against Lizardmen, each campaign in the base games has a specific flavour within Total War’s general open world of conflict. But when the horizon opens out as much as it does with Mortal Empires, geography had to change. Lizardmen players settling the expanses of Lustria might go hundreds of turns without coming across Empire or the other races from Warhammer I. “It’s important to try to redress that balance by encouraging players to come out and intermingle across the rest of the world,” Roxborough says. So there are chunks of the western edge, such as Naggaroth and Lustria, which are therefore slightly smaller in Mortal Empires than they are in Warhammer II’s standard Eye of the Vortex campaign, to push them closer to the Old World.

But more than that, faction victory conditions and starting positions are tweaked to get players to spread out into the world. Play as Karl Franz, and you’ll start as you always did in Altdorf, but his long list of victory conditions give him plenty of reason to voyage out into the New World and not, as design lead Jim Whitson puts it, “Turtle in the same place he played in the Old World.” Luckily, the sheer volume of Warhammer lore pretty much supports any character going off to duff up another. After all, the reason the setting exists is to give some kind of reason why one set of tabletop figures might be fighting any other.

Another big geographical change in Mortal Empires is its use of Warhammer II’s climate mechanic. In the first game, races had restrictions on what settlements they could hold: Greenskins couldn’t occupy any Empire territory, only raze and sack it. It was about pushing certain strategies and choices beyond simply allowing players to blindly attempt to occupy the entire continent, and it was also fairly appropriate to the lore, supposing that mountain crag-loving Dwarfs wouldn’t want to live in some dinky riverside town. In Warhammer I it worked well, because the races were divided 50/50 across the terrain types, so as any race you could occupy half the map. But Warhammer II’s more ragtag races didn’t present the same neat split.

As such, Creative Assembly knew that Warhammer I’s settlement restrictions weren’t going to last; climate mechanic was first considered way back before Warhammer I was released. “And it was a marmite feature,” Roxborough says. “A lot of people liked it and there were others who wanted to paint the whole map their colour. I get that sentiment.” Climate does both: it allows players to occupy any terrain, but if it has a climate that doesn’t suit their race it imposes various penalties, thereby allowing total domination while also steering player choices. It was ideal for Mortal Empires, holding in check any Old World faction as well as it does any New World one, while also introducing new and fresh choices to Warhammer I veterans, such as the chance for the Empire can take over Dwarfen karaks.

“It also reduces complexity for what players have to get their head around,” adds Whitson. Instead of having to note what settlements you can capture, climate is a universal law clearly communicated with a single icon. Mortal Empires’ size presents a big cognitive challenge for players as they attempt to take in everything that’s going on, so any chance to streamline was welcome. In the same way, Mortal Empires encouraged Creative Assembly to introduce various tweaks to the ways in which the game reminds players to move some army or hero, or if it’s possible to upgrade a building in some far corner of your vast empire.

One of Mortal Empires’ most immediate effects on the game is the length of its turn endings, which is when the game calculates the actions of AI-controlled factions. There are a lot of those factions. “We thought long and hard about it,” says Roxborough. “The fans are going to want all this content in, but at the same time they’ll also say the end turn times are really long, so we had to find a line.” Ultimately, they decided that since Mortal Empires was the domain of the hardcore, they’d prefer as many factions as possible over longer turn times. It was the right call. In fact, I agree with players I’ve heard say cheerfully that they see turn times as additional motivation to wipe out factions.

Still, Creative Assembly introduced new controls for what you see during end turn sequences so you can shorten them by speeding up movement of armies and heroes on a faction basis, so you can monitor allies and enemies and ignore everyone else, or just ignore everything and just see where it ends up when it’s your turn again, whichever you prefer.

One thing Mortal Empires does not tweak, however, is Total War: Warhammer’s fundamental workings. “The sandbox is sacrosanct to us on Total War,” says Roxborough. If a player is conducting five wars in a Mortal Empires campaign, another angry faction won’t hold back to give them room to breathe. “The systems are all designed to provide AI that will think on its own and do things that make sense for that AI, rather than being manipulated by us to determine the player experience.”

“Obviously, it puts more of an onus on us to balance the game, so we put a lot of thought into how we could upgrade our systems that handle that kind of thing,” says Whitson. That meant more testing, making the game playable from an earlier stage and running a lot of auto-run data, gathered by running the game’s systems and seeing on spreadsheets data on how they play out. “It’s to make sure we don’t have a runaway faction scenario, that they’re all holding each other in balance to a certain extent.”

The sheer amount of testing has made Total War: Warhammer something of an ocean tanker of a game. “The sheer magnitude of it when you’ve got not just two games but also constant DLC being fed into it, we have to constantly have to re-tweak how different races suddenly become prominent for one reason or another, and every time you put some content in it can influence the entire structure of how the races in the area develop and expand,” says Roxborough. The Norsa race, for instance, which was the final DLC released for the first game, has yet to become playable in Mortal Empires because of how much work it is to ensure they play nicely in the sandbox. (OK, Norsa would probably never play nicely in any sandbox, but you get the point.)

But Creative Assembly can still move fast when it really matters. Mortal Empires’ launch was remarkably smooth, but for one important element. Its Chaos invasion mechanic, whereby players would have to deal with northern incursions from Chaos after a certain point in their campaign, was not having the intended effect. “It was really upsetting for me personally because it was just a little blip and, ah, if only that hadn’t happened, everything else would’ve fitted in perfectly,” Roxborough says. In Mortal Empires the incursions were more challenging to suit the kind of experienced players who’d tackle the campaign and live up to Chaos’ role as Uber Bogeyman, as well as help ensure that New World races based in the south would actually see them.

But they’d become too intense. The Chaos hordes would make a beeline for and stack around the player, appearing to ignore other races you’d expect them to be attacking in a way that was not only overwhelming but also seemed contrived. As it happens, the incursions were working correctly: when it appeared that Chaos wasn’t attacking other races it was simply because it wasn’t at war with them. But it was clearly a serious issue and Creative Assembly raced to implement a fix that ensures Chaos is at war with more races, creating a trail of destruction that reduces the pressure on players and looks more natural, and issued it a couple of weeks ago.

Meanwhile, the grand project continues. Warhammer II’s DLC programme has yet to kick in (Tomb Kings, right?). And even then, Mortal Empires is far from finished. The Total War: Warhammer series will be a trilogy, which means the grandest of campaigns will eventually encompass all three games. It’ll be fascinating to see how its world of unending war will bend and twist to accommodate it.