How Gorogoa is a game about fitting things together

Land of Tiles

This is The Mechanic, where Alex Wiltshire invites developers to discuss the difficult journeys they underwent to make the best bits of their games. This time, Gorogoa [official site].

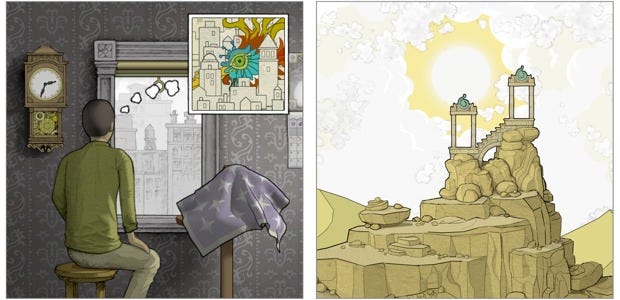

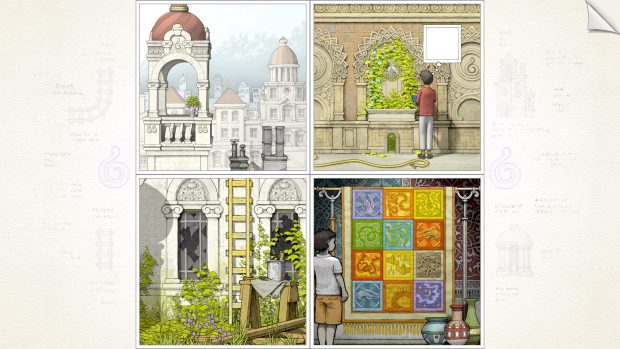

Gorogoa is a game about fitting things together. Fitting a detail in one image with a detail in another and see how it produces something new. And in making it, developer Jason Roberts found that making things fit was one of the greatest challenges he faced, whether those things were puzzles into the game's tiles, sequences into its story, or details into players’ heads.

Gorogoa is also a game about linking things together. You draw relationships between images and find them leading into and influencing wider themes. And in making it, Roberts found that each decision he made had profound effects on others, the biggest being limiting the game to its two-by-two grid.

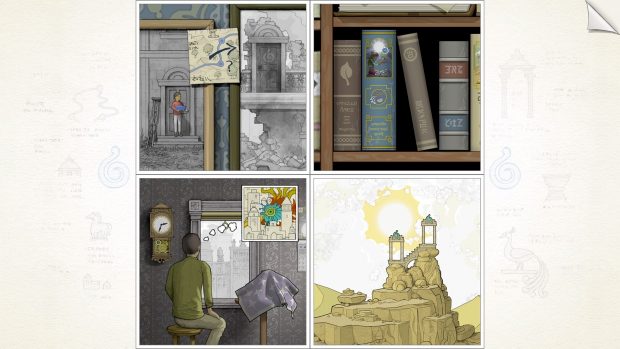

If you haven’t played Gorogoa, the four tiles that hold the images you swap around and zoom in and out of might look painfully restricted. Surely the range of possibilities in the configurations of images would be so low that you’d stumble on solutions just by clicking around? Solutions aren't simply about sequence though; you're not reconstructing panels in a comic strip, you're playing with space. But, initially, Roberts himself thought the four tile configuration might be limiting. He wanted a three-by-three grid to accommodate more complex puzzles, but soon saw how that just didn’t work.

In practical terms, with six tiles each image became too small to be able to see the details, which would mean creating some kind of crude zooming system. But more than that, six tiles was just too much for a player to take in. “I wanted each scene to be very deep and have lots of detail,” Roberts tells me. “Four scenes seemed to be the limit of what people could keep track of, and that was pushing it. I’m glad it didn’t get bigger. I know that when people saw the game early on they said, ‘Oh, this is too simple, there’s only four tiles and a really small number of permutations’. But four turned out to be the sweet spot.”

In fact, even with only four tiles, Roberts found himself having to be very careful to limit the number of options in a scene and to guide players’ attention. For example, if a scenario contained a detail which wasn’t useful yet but would be in the next sequence, or had outlived its usefulness, Roberts devised ways of gating it off to avoid the player fruitlessly investigating it.

But he didn’t make it easy on himself. One thing to understand about the way Roberts designed Gorogoa is that everything that happens has to seem reasonable. Maybe not strictly logical, but when a detail is revealed or removed, you have to be able to divine why. “Something in the scene has to change,” he says. So one early sequence is set in a room with a low cloth-covered table, and at a certain point the cover blows away to reveal objects below it. “Before it was there, you could dive all the way into the stuff on the table before it’s necessary, before you needed it, and that pushed the cognitive load into the red zone,” says Roberts.

These changes couldn’t be wholly arbitrary. A picture couldn’t just suddenly fall from the wall, or boards fall away from a window. Events and changes to the scene had to be caused through some kind of agency within the game world, and not by the player directly, because Roberts decided that players couldn’t touch anything in the game world. You’re purely an observer.

“As soon as I allow the player to fiddle physically with things in the world there comes this temptation to create challenges that exist only within one tile, and I wanted to make sure that wasn’t true,” he says. “The handicapping of the player is part of what’s interesting in design. All you’re changing really is what you’re looking at in any of the tiles. The source of all your power is where you choose to look.”

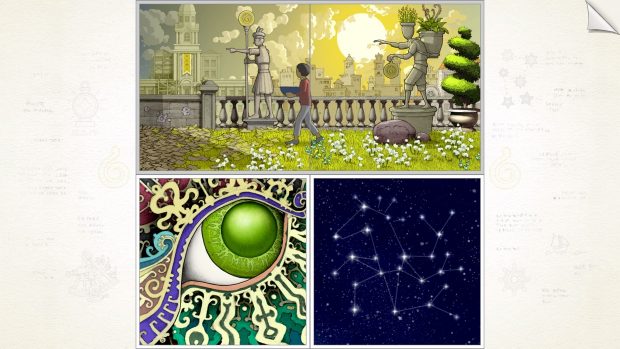

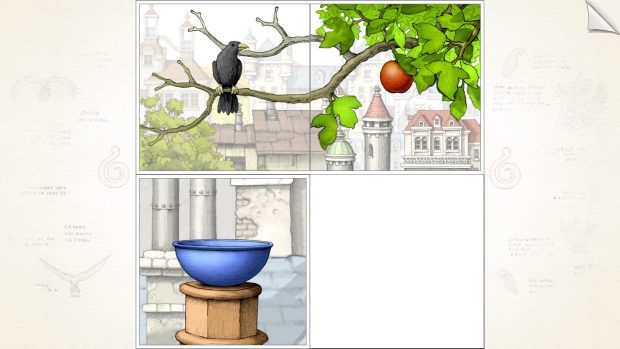

Looking back, he’s glad he imposed that limitation on himself, but it created a lot of challenges, requiring mechanical changes in the world which the player didn’t directly set in motion. So for a puzzle in which rocks begin to fall he had to invent a reason why (they’re spilling from a container which has fallen over), and in the very first section, when an apple falls, he had a crow taking off. “Maybe that’s a little arbitrary,” he admits. And for each, it meant making more tiles, more images and animations.

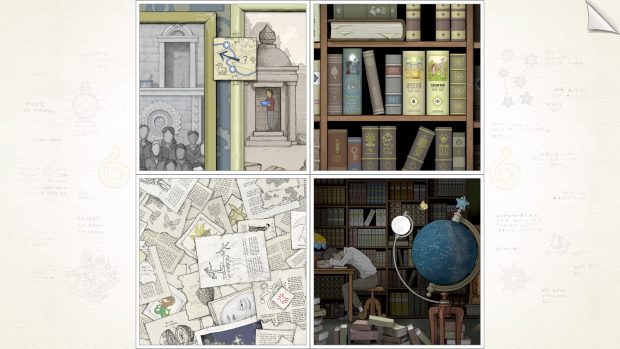

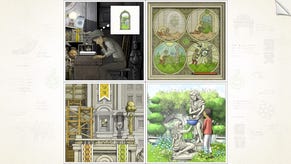

These animated sequences were time-consuming to create. Roberts drew each frame in Photoshop, where he’d colour and light it, before pencilling outlines. One mistake in the first stages of development was to polish and finish artwork too early; facing a game which didn’t really work yet, he found the act of working on art soothing and relished the immediate positive feedback it won him. “After a while I learned my lesson,” he says, because he realised he was spending a long time on art that would end up being changed.

Still, Gorogoa’s art had to be surprisingly finished - 85%, Roberts estimates - before it’d prove whether it worked. “If you think about the falling rock puzzle, mechanically all you need is the physics of the rock falling and objects placed so it takes long enough to fall through each scene. Or in the same chapter the boy walks from right to left through the whole chapter and the scene starts at sunset and ends at night. The concept is simple: I connect one thing to another and the character crosses. The hard part is, can I make these two scenes connect and individually not look strange?”

One big issue was lighting. Since players spend the game fitting images together, they had to look consistent with each other in two dimensions: in their natural setting and also when solved. Yet if one image originates in a scene in a dark room lit by a lamp, and the other in an exterior by day, the temporary art needed to feature enough lighting to convince him it all looked as natural fitted together as it did in its original setting.

The game’s two-by-two grid also affected the design of its puzzles. If a puzzle required three tiles and its setting required two, he’d have to design another puzzle specifically to consume a tile to make space. “That had a huge influence on the design,” Roberts says. “The constraints were what was challenging and interesting about the design. A lot of times the more interesting things came out of trying to connect to or do things together, or being forced to get rid of tiles.” The coin puzzle in the later game came out of Roberts thinking about how he could consume two tiles.

Similarly, sometimes two scenes would be set in different times and spaces. “I’ll have two things I know I want and realise I need to make something to connect them, and then the idea that I’m forced to come up with to connect them often ends up more interesting than what I’m connecting, or the functional role that it’s playing. To move between and in and out of memories and things like that, that turned out to be among the more interesting things you’re able to do in this game.”

Because Gorogoa is so much about these connections, about relationships rather than purely mechanical cause and effect, Roberts’ puzzle design walks a tightrope between logic and dreamy surprise. He’s well aware that he could’ve gone badly wrong, and for its original 2012 demo he teetered towards one side of the balance. “I was mostly concentrating on making something delightful and full of surprises and things that would feel magic,” he says. He noticed it divided the people who played it. There were those who enjoyed its world and connecting the images, and there were those who expected its puzzles to be more fulfilling, more logical and involved. “If you’re making a puzzle game that involves reasoning, reasoning requires making predictions about systems and that runs contrary to delightful surprises.”

Roberts felt that if the game became more drily mechanical, it would lose some of its magic, surprise and variety. “To make puzzles work more clearly you can ramp up repetition of the mechanics - the simple version, the slightly more complicated version - to teach people little by little, but I wanted everything to be bespoke and feel different.”

His solution was to build repetition into the structure of the chapters, so you explore different facets of similar ideas, such as in a sequence that relates to turning gears. And he also tried to build a discovery phase into puzzles, so you can find things that look similar and you connect them, not knowing at first why, providing a moment of surprise and delight which doesn’t in itself get you to the solution. “Always leave the player with something to figure out, even if it’s just the last piece of the puzzle, because I think that feeling is essential to some players and is not objectionable to people who are less interested in puzzles.”

The last puzzle he designed was the falling rock puzzle. He doesn’t think it’s the strongest one in the game but feels it’s very important, because it’s the first that you can’t accidentally solve because you need insight into what’s happening. “It’s a simple concept but you need to put some effort into executing it, and at that point the player gets a sense - I hope - that’s reassuring: ‘Oh, I got something. Even if I’ve been fumbling through up to this point and it’s a weird game and the mechanics are strange and magical but I can figure this out.’”

When you finish Gorogoa, there’s a sense that you haven’t experienced everything its base design can achieve. Though the challenge escalates, it doesn’t ask you to connect all four tiles or anything like that. It’s partly down to Roberts’ own opinion of expressing design: “There’s this almost ethic of mechanical completism amongst some indie developers, where you almost have an obligation to explore every implied possibility in your mechanic. I decided early on that I wasn’t taking that approach of fully wringing out the towel of possibilities.”

But there was another reason. Many puzzles just didn’t fit into the game’s pacing and structure, and Roberts was comfortable leaving good ideas behind if they’d distort it. Since the game has the air of a fable or allegory, its symbolic qualities of symmetry and balance was important. A sequence would have three puzzles and not four. “There was never any place to add more puzzles without putting in scenes that aren’t necessary for the story, and in fact could hurt the story. The same goes for more complex versions of the same puzzles,” he says.

Gorogoa is a game of rigorous self-imposed limitations, the kind that inspire a game that manages to balance magic with logic, surprise with prediction. But aside from their aesthetics, there are also practical benefits of limitations. In making a game with no precedents, choosing Gorogoa’s limits created its shape. Roberts just had to fit things into it.