Butterfly Soup makes an excellent case for why representation matters

Possibilities make more things possible

The brilliant 2017 visual novel Butterfly Soup by Brianna Lei is a story about many things. It is about the pains and prides of growing up Asian American in Oakland, it is about coming out queer, it is about playing baseball and living in a society that only pretends it's no longer racist. It is about coping with emotional distress and anxiety, it is about homophobia, both internalized and overt. It’s about redeeming love for dogs. And it is also about representation.

By that I do not mean it is a game that provides good representation; the diverse cast of characters that make up the story have roots all over Asia, and the narrative constantly draws attention to various aspects of Asian-American life, from the differences between “normal passing” and “Asian passing” in tests at school, to language troubles between people who, although lumped together as “Asian” come from vastly different backgrounds. Yet, it is not for me to judge whether this is good representation - I am neither Asian, nor American and I do not want to presume. What I can say with full certainty, however, is that Butterfly Soup makes an excellent case for why diverse representation matters.

To explain, I’d like to go on a small tangent first. I was recommended Butterfly Soup by the algorithm on the itch.io storefront, which noted that I seem to have interest in visual novels with queer themes. And that’s true, I do actually like to read about queer people! But what does this “queer people” even mean here? Terms such as “gay”, “lesbian”, “transgender”, or “queer” are not neutral, universal descriptors. Although we tend to use them as if they could accurately describe any sort of non-hetero attraction or sexuality, the matter is more complicated than that.

Along with the development of lesbian and gay studies (and later queer theory), there’s been a consistent stream of critique coming from post-colonial writers, or just people who are not Western, not from the Global North, not White. What they have all been indicating is that the history of “gayness”, “lesbianism”, or “queerness” is of concepts developed in the West, to describe particular Western experiences and cultures, and then often employed as if they could fit experiences of everyone else on the planet just the same. As if being in a gay marriage in the 21st century New York meant the same thing as being in homosexual relationship in pre-colonial India.

And so Butterfly Soup isn’t just a game about queer people, it is a game about queer people from a specific background which is constantly brought up and depicted as informing their queerness.

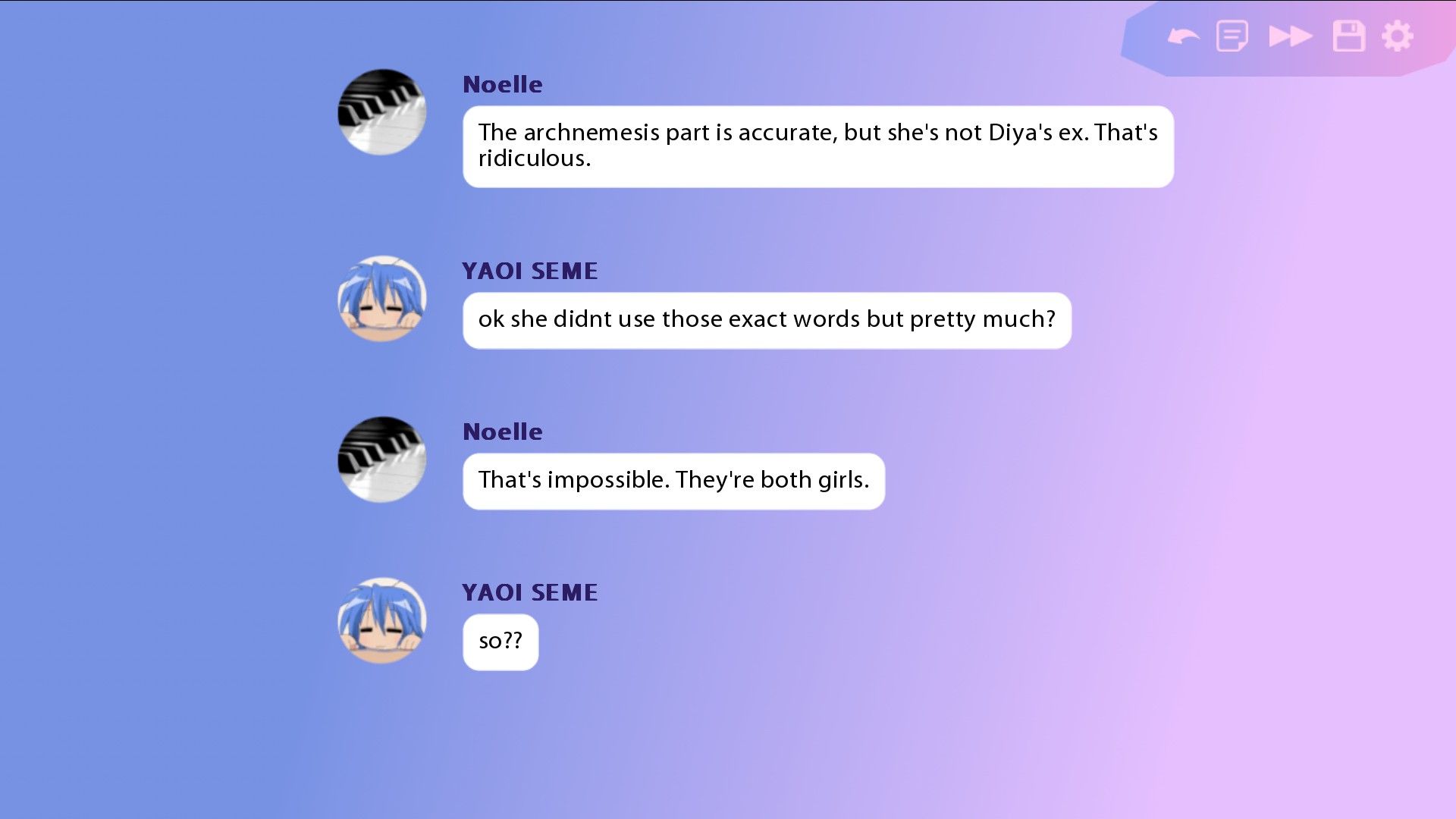

But are they even “queer”? The word itself isn’t used in the game at all, and in fact, the narrative and dialogue are very light on such labels. Between the four main characters Diya and Akarsha, Min-seo and Noelle, only Akarsha is comfortable with actually using the contemporary Western language of sexual orientation to describe herself. For others, the labels are a confusing challenge (and a source for a lot of great humour when they struggle to articulate their feelings). And for Noelle, the very idea of a same-sex relationship is something that she at times struggles to conceptualise as actually possible.

But should we understand their difficulties as the result of their growing up in an insular Asian-American world (in flashbacks to their earliest years, we saw one of them wonder what the percentage of white people is in the US was, and guessing that 4% would be about right)? Or is it just due to the general confusion and struggle of growing up, which also serves as one of the game’s important themes? One of the interesting motions in Butterfly Soup’s narrative is how it flips the script on a certain idea on where (and among whom) queerness is possible.

The post-colonial criticism of queerness as a Western thing is not usually a criticism of the West “spreading the gay”, like the propaganda of some states - states that are otherwise often understood as “Western” - likes to picture it. Looking at you, my homeland.

Instead, it often focuses on showing how the narrative of the West as the cradle of gay rights can be then used to justify prejudice and xenophobia, branding “the East” (either as a geographical place, or as a designation of a community) as a site where living as a queer person is just not feasible. The implication then becomes the notion that those who desire a fulfilling gay life must be either (but often both) life in the West or in assimilation to Westernness, which is seen as the only pillar on which LGBT+ rights can be built.

The bulk of Butterfly Soup’s story is set during 2008’s election season in California, when Proposition 8, seeking to eliminate the rights of same-sex couples to marry, was put on the ballot and then passed. Campaigners for this initiative make up the background noise of the story. Alongside the recurring refrain of the characters being confronted with racist catcalling and heckling - which scares and confuses them because the school they attend keeps telling them that racism in the US is over - the campaign and its success spoil their own idea of the country their families immigrated to being one that will welcome them, even if they're different. In fact, homophobia and racism go hand in hand as representative of White America.

And this is what I mean when I say that the game is about representation. All the way through the story the characters are confronted with the notion that they don't have a place in the world. This theme first materialises around baseball, but reaches so much farther. Min-seo’s idea that she can play baseball is ridiculed and not taken seriously, because no one in her family or among her friends had ever seen a girl play. Diya, even though she is supremely athletic and obviously talented, can’t conceive of herself as a sportswoman because there are no Asian women she knows who play in major sports. Noelle fails to imagine romantic love between women because there are none she can recognise in the world around her. Even when Akarsha shamelessly flirts with Diya, the latter doesn’t notice it, because she has no frame of reference.

But when Min-seo sees Diya as the lone girl playing baseball in a group made out of entirely of boys, she sees her own desire to play as within the realm of possibility. It derails the life others conceived of for her, and opens the door for being her own person. In a way, it’s a small thing, but it is to such small things that the player’s attention is drawn over and over again, as the characters see themselves represented and attempt to act on it.

And, in many ways, it is what the game does. It portrays four queer Asian American girls coming to terms with their sexuality and desires. It does not require them to integrate, or to leave their community, in order to do so. For all the difficulties they have with their families and themselves, they can be both queer and non-White, and there is no contradiction there.

The power of representation does not come from the idea that stories which are more diverse are somehow inherently better, but rather from how it allows us to think of certain ways of living as at all conceivable. If there are no female heroes, we struggle to imagine what a female hero would even look like. If narratives and theories of queerness constantly go back to whiteness and certain notions of Westernness, people who are none of that can find it difficult to also see themselves as possibly queer.

I cannot speak from an Asian American perspective. But this issue isn’t limited to just America. Even where I live, in a country that is ostensibly Western, a part of the European Union, the narratives of gay struggle for identity developed in the English-speaking world do not necessarily apply locally.

To give just an example: every year, come Pride season, I keep hearing debates about the appropriateness of police presence during Pride festivals. Mostly from friends on the internet, but often enough also here, on the ground. But how do the arguments about that issue, raised in the face of the particularly US history of police violence, apply in a country which didn’t have its Stonewall, didn’t have its organized persecution of sexual minorities by the police (which is not to say there was no such persecution by various state services)? Do they even apply at all? It may seem like a small issue, but it is just the tip of the iceberg: the debates and conflicts within the US LGBT+ community are exported alongside with the US’s culture and norms, and often end up covering up, if not overwriting, local histories.

Butterfly Soup is a small game. You can read through it in about two hours, maybe even less. And, at a glance, it really isn’t much: just a few gay Asian American girls playing baseball and exchanging dank memes in group chat. In a way, it is a supremely mundane deal. But because of that, it allows us to see those experiences as real and liveable. It is a game about representation - it is a game about how showing possibility makes different living possible.