How Tunic was born from a lifelong obsession with Zelda, secrets and hidden object games

Creator Andrew Shouldice tells us about designing "the excitement of not knowing"

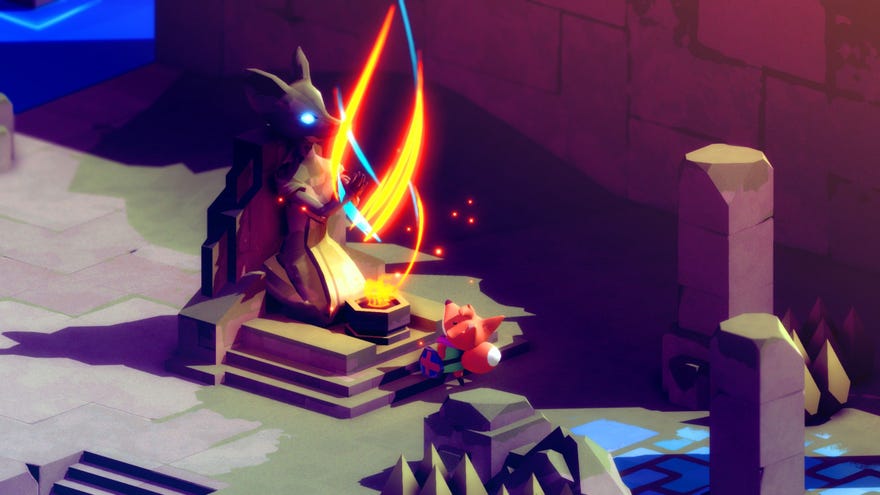

Tunic developer Andrew Shouldice has made no secret about his love of The Legend Of Zelda over the years. He's not only spoken at length about how playing the original pair of Zelda games on the NES provided ample inspiration for his crafty hack and slasher, but you can also see it right there in the game itself, from your fox hero's bright green outfit to the beautifully illustrated in-game manual you piece together to unravel the world's mysteries.

But speaking with Shouldice at GDC this year, I wanted to talk to him another other potential source of inspiration. Before he struck out on his own to make Tunic, Shouldice cut his teeth making hidden object games, ranging from globe-trotting mystery adventures to Atlantean-themed detective stories. On paper, this earlier work would appear to provide the perfect proving ground for Tunic, as we all know by now that it holds plenty of secrets of its own. For Shouldice, though, it was more of a reaction against his earlier work that fuelled his approach to Tunic, as he gradually came to realise his hidden object games "weren't tapping into this very specific type of mystery and discovery and player agency and true exploration that I was interested in," he says.

Shouldice remembers he wore "a number of different hats" at his first studio, working on everything from UI to programming, art, puzzle design and planning. It's a mentality that's served him well as a solo dev, as doing so many jobs early on meant he eventually felt like he had "sufficient points in each stat" to make something of his own. Admittedly, some of those stat points came from mucking about with making pen and paper games as child. "That definitely let me point more points into each of those categories," he says, even if he didn't quite know it at the time.

When he eventually started making games professionally, those early childhood forays into game design came roaring back. "I ended up using some techniques that I did when I was a kid, which was making point and click adventure games in my head and on graph paper, like drawing dependency graphs," he tells me. Later in life, once he started attending computer science classes, he discovered that those graphs had a proper name: directed acyclic graphs, or DAGs, and their strict lines of cause and effect provided a neat template for his hidden object work.

However, as much as Shouldice enjoyed making those games, when he tried applying the same graph model to an early outline of Tunic, he realised it didn't quite fit with what he was trying to do. Those tools "weren't actually appropriate for something like Tunic," he says. "Those rigid graphs didn't allow the sort of expressivity and wonder and 'pick a direction and go' sort of feeling that I loved from the games that I enjoyed as a kid." As a result, he needed to approach it from a completely different angle if he was ever going to make good on his initial design goals.

"Who knows, maybe that was the beginning of an important genesis, you know? Understanding rules and how to break them is maybe important to doing something new and interesting," he ponders. "But those DAGs that I was talking about, the graphs of dependency, were a thing that I started with when developing Tunic. Like, 'Oh, you need sword to chop down bush, you need key to open door.' I started with that sort of mentality and realised, 'No, I want exceptions at every step of the way.'"

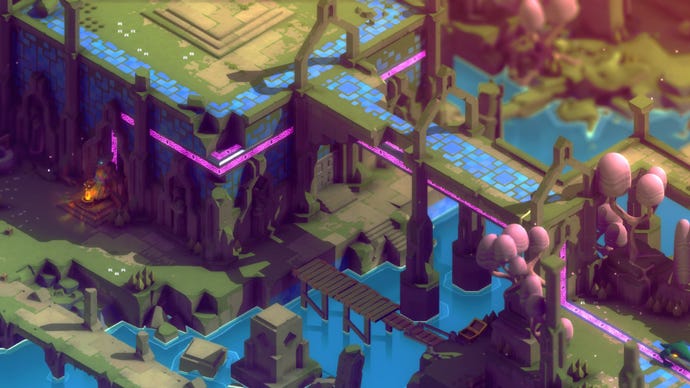

As a result, hard progression gates were out of the question. "I wanted there to be a way to get something early that lets you get past these bushes without even picking up the sword," Shouldice continues. "I want this door to be something that you can actually circumvent if you want, and so that formal structure needed to turn into a much, much mushier soup."

That's not to say that soup didn't still have some important chunks left in it at the end of it all, though. There were still a number of design principles form his hidden object days that served as an important foundation for Shouldice, "like pacing and drawing the eye and using things to pull the player in a particular direction," he says. "So if you make a game where you can do lots and lots of different things, and you can get yourself into a lot of trouble, that's cool and great and wonderful. But you probably also have a semi-critical path that you're hoping people will find their way down. Even though you don't technically need to get the sword, we still want you to get the sword first."

Indeed, as anyone who's played Tunic will know, there is something mercurial about the way it guides you through its world. Wherever you look, there's a sense of wonder and curiosity that's constantly tugging at the edges of your understanding, but you also feel like it's pulling you in a very specific direction at the same time. Just before our interview, Shouldice presented a talk on this exact subject, and in it he said he'd spent a lot of time trying to articulate exactly the kinds of feelings he wanted to evoke in Tunic when people eventually sat down and played it.

"Mystery" would be the easy way to describe it, but really it's "the excitement of not knowing, or rather, of knowing there's lots to know, but not knowing it yet, and knowing you could know but nobody's expecting you to know (so nobody will know that you know when you do eventually know)," he laughs. And the place where that excitement is felt most strongly is when you're right in the middle of discovering one of its secrets.

"The lifecycle of a secret, or really learning about anything in a video game can be separated, I think, into three phases," he explains. "You start not knowing the thing. That's the ignorance phase. [Then] there's knowledge, where you know something exists but you don't understand it. And then eventually you do understand it. Understanding is closure. That's where something has clicked and you turn mystery into comprehension. It is now a solved mystery."

But it's the knowledge stage that Shouldice likes best - when you have "the bits of a jigsaw and you want to fit them together," as he puts it, in order to reach that level of understanding and sense of accomplishment. "I like having lots and lots of paths in my head when I play video games, lots of loose ends that I'm excited about, and I think the reason is that curiosity and speculation is fun," he says.

It's a sensation that stems right back to playing Zelda games as a kid, he tells me - or rather, watching someone else play Zelda while he pored over the instruction manual. Shouldice admits his first real memory of Zelda is a little hazy now, but "I was doing that thing that I did a lot when I was a kid, which was looking through the instruction manual while someone else was playing it, and letting that thing happen where your imagination takes over.

"I think things like engaging with this ephemera at the edges of the game without actually engaging with the game itself lets your imagination run wild a little bit, and I was reminded recently that I spent a lot of time as a kid checking out books from the library that were like, 'How To Win At Nintendo Games,'" he laughs. "Those were just paperback walls of text, prose with no illustrations, but I was reading about these games that I would never see, let alone play, […] and I feel like that was maybe an important moment cognitively, you know? Dreaming up all of these things that were described. Like they're there, they're clearly real, someone who wrote a book about them, they exist, but not having the limitations of actual 8-bit hardware impinging on my childhood imagination."

Even now, though, it's clear that Shouldice still has a lot of love for the old Zelda games. He tells me he recently started playing the notoriously hard, remixed Second Quest in the original Legend Of Zelda, which he concedes "is a wild thing that's full of some truly mean design decisions." But its vanilla form is still something that's exciting to him as well, he says. "Not the game itself," he clarifies, "because it's long since been emptied of a lot of [its] wonder. But it's still fun to think about and try and capture that."

Thankfully, we're not just limited to games from the NES and the early PC era anymore if we want to find something that fits Shouldice's lifecycle of a secret model. Games such as Outer Wilds, Return Of The Obra Dinn, Breath Of The Wild and, of course, Tunic itself all thrive in that knowledge phase of curious speculation, and it's precisely because they're able to dangle so many threads in front of their players like this that I think they've created such a strong and enduring resonance with those who have encountered them. Then again, Shouldice also admits that he had to actively avoid some of those games I just mentioned until Tunic's development was finally complete.

"Playing games and being inspired by them is usually pretty thrilling for me," he says. "[But] sometimes it can be depressing when something's close enough that you realise, 'Oh gosh, they did this so much better than I ever could have dreamed.' […] Like I didn't play Outer Wilds during development, because everybody told me that it was exactly my jam. And I knew if I played it, I would just curl up into a little ball and disappear forever. So I saved it. And I'm glad I did, because I was able to play it and enjoy it, as it was intended to be enjoyed, not dissected to be turned into inspiration."

That said, he does also admit to still being a tiny bit envious of the way Outer Wilds manages to keep track of all its individual lines of investigation via your ship's computer. "In retrospect, some way of marking up [Tunic's] manual yourself would have been neat," he confesses. "A way to just like put stickers on places of interest or add notes or something. I want to spend more time thinking about it, because one of the threats with making a game [like this] is that if you lose the thread, you've lost the thread," he laughs.

"The fun part is juggling all of these loose ends, all these paths in your head, but if you come back, and you're like, 'All right, what am I doing?' No idea. Because all of that's just fallen out. I mean the easy answer is 'bust out the notebook and compare the results'. But that's not always feasible. Sometimes you can tell if a game is supposed to be a notebook game, sometimes you can't. So I think having some sort of built-in note taking capability might have been a cool thing. Maybe not in Tunic but some other game. It's interesting to think about."

Ultimately, though, Shouldice isn't afraid of being "arbitrarily complicated" with the way he designs his secrets. Making "content for no one" is all part of the fun, he says. "That means you have secrets that we can feel as players, whether it's glimpses of them that we get first-hand, or we hear hushed community chatter about something. Those secrets will exist and sort of subtly radiate this feeling of mystery out into the rest of the game." For Shouldice, then, the most valuable thing of all is a mystery that never ends - and he concludes our chat by saying that if he could "just invent a fantasy world where I play Zelda I and realise that there's a mechanic in there that no one knew existed miraculously, despite having been completely decompiled, that would be my wonderful, secret history that goes on forever." Not before he's played Tears Of The Kingdom, though. "Who knows what comes next with that."