In Cook Your Way you must cook a meal with a strange controller to get through immigration

The melting pot

“It brings this idea that you are doing something similar to cooking, but at the same time isn’t that at all.”

Enric Llagostera wants to do something unusual for a game about cooking: to make it discomforting. Drawing from his experiences as a Brazilian migrant in Canada, he wanted to simulate the feelings of confusion and tension of the immigration process by disorienting the player. To do that, he would use food, and a very unusual controller.

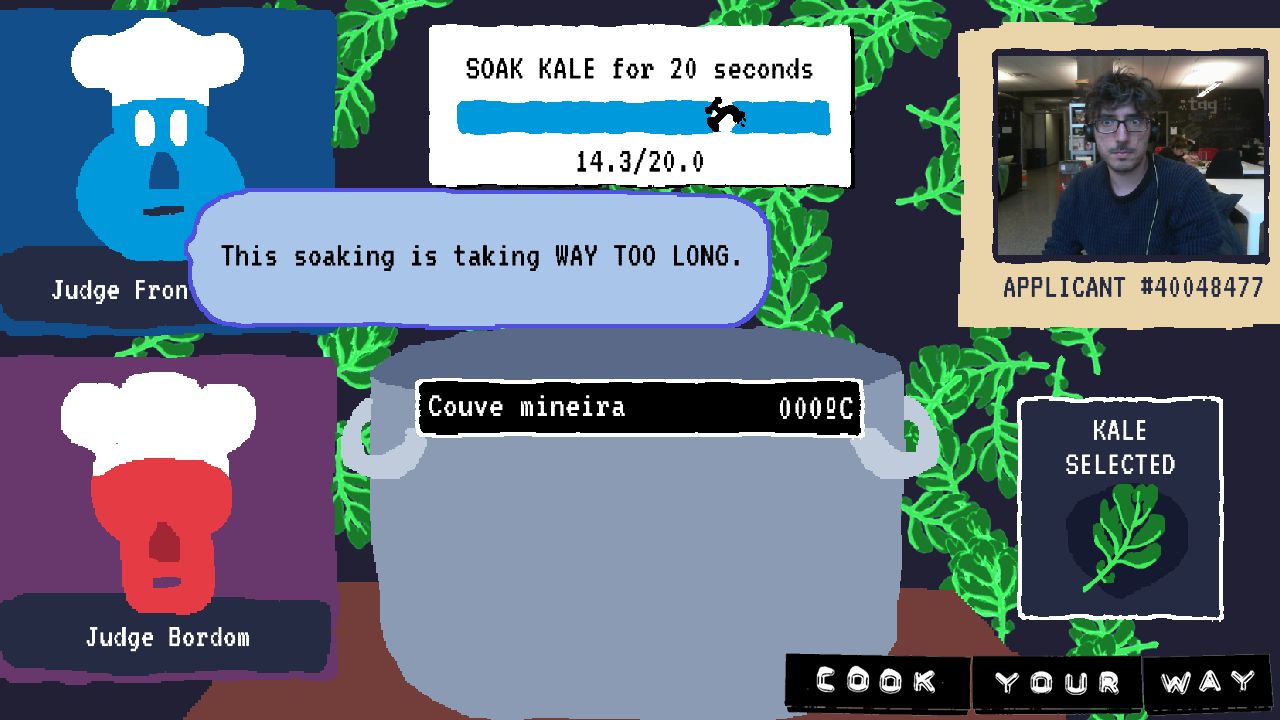

In Cook Your Way you play a Brazilian person applying for a visa to move abroad, and you have to prove your worth to border agents by cooking a feijoada, a traditional Brazilian dish which usually consists of a stew of black beans mixed with a variety of pork cuts. The test is staged as a cooking reality show, where the border agents – named Bordom and Fronteirini – are dressed as chef judges, and will “chat” with you about your past and qualifications while you cook.

There’s a lot going on. Llagostera calls this combination of cookery and questioning as “uncanny juxtapositions”. By mixing together conflicting concepts, he wants to make the player reflect on the average immigrant’s experience.

That “reflection” is key. Cook Your Way is one of the projects from Llagostera’s Ph.D. research at Concordia University. As part of the Reflective Game Design research group, he’s investigating how alternative controllers can incentivise players to criticise and interrogate their experience with a game, rather than just playing thoughtlessly. The group values “questions over answers” and “disruption over comfort” in order to create experiences that make both players and designers confront situations they don’t fully grasp yet. Hopefully making them reassess their previous beliefs.

“The game isn’t going to solve any questions,” says Llagostera. “The idea is that by interacting with it, you will raise your own questions to think about.”

As he took part in the group’s discussions and experiments, Llagostera often found himself thinking about his experiences as a migrant – the move to Canada being the third time he left Brazil. Food was a common thread.

“You are away from family, away from friends,” he says, “away from these references that we have and that help us to deal with a lot.”

But he notes how much of his social interactions were around making and eating food. Food is also something that commonly comes up in conversations about immigration. Llagostera cites an article he read which argued that “the more immigrants, the better the food” as something which became an important inspiration for the game.

“It was a horrifying argument.” he assures me. But it served as one of the premises the game.

While it focuses on food, Cook Your Way aims to use cooking as a proxy to critique how immigration systems deal with all forms of labour.

“The discourses [around] immigrations systems always focus on what the immigrant produces, economically or culturally,” says Llagostera. “It’s either that or an absurdly criminal vision of the immigrants. They believe that there exists a good and a bad immigrant, and the difference between them is related to productivity and what generates value.”

Llagostera saw a lot in common between these arguments and the stories often present in shows like MasterChef and Nailed It.

“Reality shows argue for this idea of meritocracy, which also has a strong record in immigration discourses. In these shows, you are under equal conditions, everyone has the same standard equipment. Only the individual matters. Every type of inequality present ends up being erased in the process.”

From this came the idea to present the application test as a cooking contest. You’re being interviewed while cooking, having to answer yes/no questions, such as: “Have you ever stayed beyond validity of your status in any country?”

“A lot of the questions were taken directly from immigration forms,” says Llagostera. After finishing each part of the meal, there are intermissions where the screen focuses only on the camera feed of the player, and you are asked to answer more open-ended questions.

“Sometimes people look at me with a face like ‘so, should I talk?’ and then I just shrug, as if to say: ‘You tell me.’ The game continues no matter what. It doesn’t need to measure what is being said, just raising these doubts is enough.”

In one of these breaks, I was asked to “detail my employment history for the last ten years.” I got confused if I should include my freelance work, but no clarifications were offered. I had 18 seconds to answer this. This game can be really stressful, and it’s something he’s concerned with. These intermissions, while tense on their own, also serve as a sort of break from the intensity of the cooking, which Llagostera noticed tired players quickly.

There’s not much place for joy or creativity in Cook Your Way, as cooking is reduced to an abstract, mechanized form. Every interaction is evaluated both by the judges and by visual indicators like the status bars for each ingredient. You follow instruction after instruction, manipulating ingredients and utensils like they are levers of a machine.

“It will say ‘Chop Onions’, so you add an onion and press the knife. Then you remove the onion [cartridge] and it hasn’t changed at all. It somewhat negates what you just did.”

Llagostera developed a cooking station controller, including a pot, a knife and dials for controlling heat and water flow. The controller was made to resemble industrial equipment. The ingredients are represented as cartridges, formless, with no texture or smell unique to them. At first he planned to have two pots, so the player had to cook more than one dish at a time, but he soon found one pot to be chaotic enough.

“It was already too stressful,” he says. “I didn’t want the difficulty to come from the physical actions, but from the themes of the game. Some of them are difficult to execute, but I tried to make it so it wouldn’t be the main challenge.”

He has made a keyboard-only version of the game, but he’s not sure if it would work.

“I think the object does a really important job,” he says. “The controller has things in it that I think are relevant - the gestures, its materiality, its visuals.”

Llagostera sent me a demo of the keyboard version, which I played before we talked. At first, I thought it worked really well, the clumsiness of using the controller being replaced by trying to figure out which key does what. But during our talk, it became clear that playing in a controlled environment like my living room diminished the feeling of alienation and the feeling of being observed. Because that’s something else about the game: there’s a camera broadcasting everything you do (although it doesn’t store or process any of the data). On top of that, this is mostly an “events” game - something to be brought to shows and played in public. All of which heightens the stress.

“The intention is to [create] distance from oneself a bit,” says Llagostera. “When you are playing it in public and someone passes by, you end up stopping because of that and then you’re reminded that you are playing in public. Sometimes people get tenser, sometimes it ends up in something more humorous. I think people getting self-conscious and interacting somehow with the camera is something interesting. It’s a cool tension. Brings attention to like: ‘I’m interacting with this cooking interface, but it is observing me.’”

Although Llagostera wanted to tackle how these systems affect all migrants, the limits of his background appeared early in development.

“I had several crises. Like, should I really be telling this story?” he says. “It became clear since the beginning that I’m speaking from a really specific point of view, as someone who has a determined set of privileges: I’m white, cis, straight - I have a visa. I’m also watching the world burst into flames while I develop the game... It was difficult to decide what I could and couldn’t engage with in the game.”

The decision to have a Brazilian protagonist came from these anxieties.

“I have references to what are the stereotypes and what are the questions and things related to Brazil that occur overseas. I felt like I had a foundation to play with that. To make diagonals and connections.” Llagostera says.

But tying the character’s background to his own didn’t feel like it did enough to respect the diversity of migrant experiences. So he has developed mod tools so other people can create their own ingredients, recipes and dialogues for the game.

“The idea is to organize workshops where we play the game, we talk and discuss the experiences and then we modify the game. To change the game and its scenarios and recipes - or to imagine what type of stories people would like to play inside this game. So it can serve as an object that creates discussions.”

“I never planned to make a faithful representation or a ‘immigration simulator’. It was about raising questions: ‘Why does the kitchen look like the set of MasterChef? Why reality shows share similarities with immigration?’ And then seeing where these questions takes us.”