Premature Evaluation: Landlord's Super

Whippet good

Everything I know about the post-industrial decline of Britain I learned from listening to Ghost Town, the 1981 hit song by The Specials about some spooky creeps who hijack a Vauxhall Cresta to hunt down Margaret Thatcher. There’s also the time I fell asleep on the couch watching The Full Monty and woke up to Fight Club, which saddled me with a false memory of Robert Carlyle breaking into a liposuction clinic to steal bags of human fat. To this day, I cannot picture out of work northerners without imagining them pilfering sack after sack of warm pink goo to fund their entry into a dance competition.

Landlord’s Super is set in the dismal and rain-battered fictional town of Sheffingham, where the cruel rot of Thatcherism has taken hold and misery is chiseled into the haunted faces of everyone you meet. A well-observed mix of environmental design, an allegedly dynamic weather system that seems permanently stuck on inclement, and a visual filter that strips away all primary colours in favour of shades of nicotine-brown, articulates the mood of the era nicely. Imagine Stardew Valley with all the hopefulness stripped away, where instead of growing cabbages and marrying a goth you’re getting daytime drunk on £1.50 pints of warm ale and pissing in cement mixers.

You play the son of an immigrant, fortunate enough to have come into possession of a right-to-buy property on the outskirts of town. Armed with a wheelbarrow and the singular aspiration to slip the surly bonds of the working class to become a landlord, it’s up to you to renovate the ex-council house to a standard that it can be eventually rented out privately to somebody slightly worse off than you. As this is a fantasy game about being a landlord, you do this by getting your hands dirty: constructing foundation frames, mixing and pouring cement, trowelling mortar, laying bricks, tiling the roof and occasionally fainting from exhaustion next to a skip.

The work required to repair the house is all fixed, a linear series of jobs to be carried out in a prescribed sequence rather than some open-ended creative endeavour, but each task feels distinctly interactive. Supplies and tools exist not inside magic pockets but in physical space, typically in unorganised piles dotted around your building site. Each individual brick and plank must be procured, carried and positioned by hand, every nail methodically hammered into place. This gives the game a real sense of hard graft, helped along by an energy meter that drains away with each unloaded bag of cement and a hygiene meter that fills up with muck as you toil about in the mud.

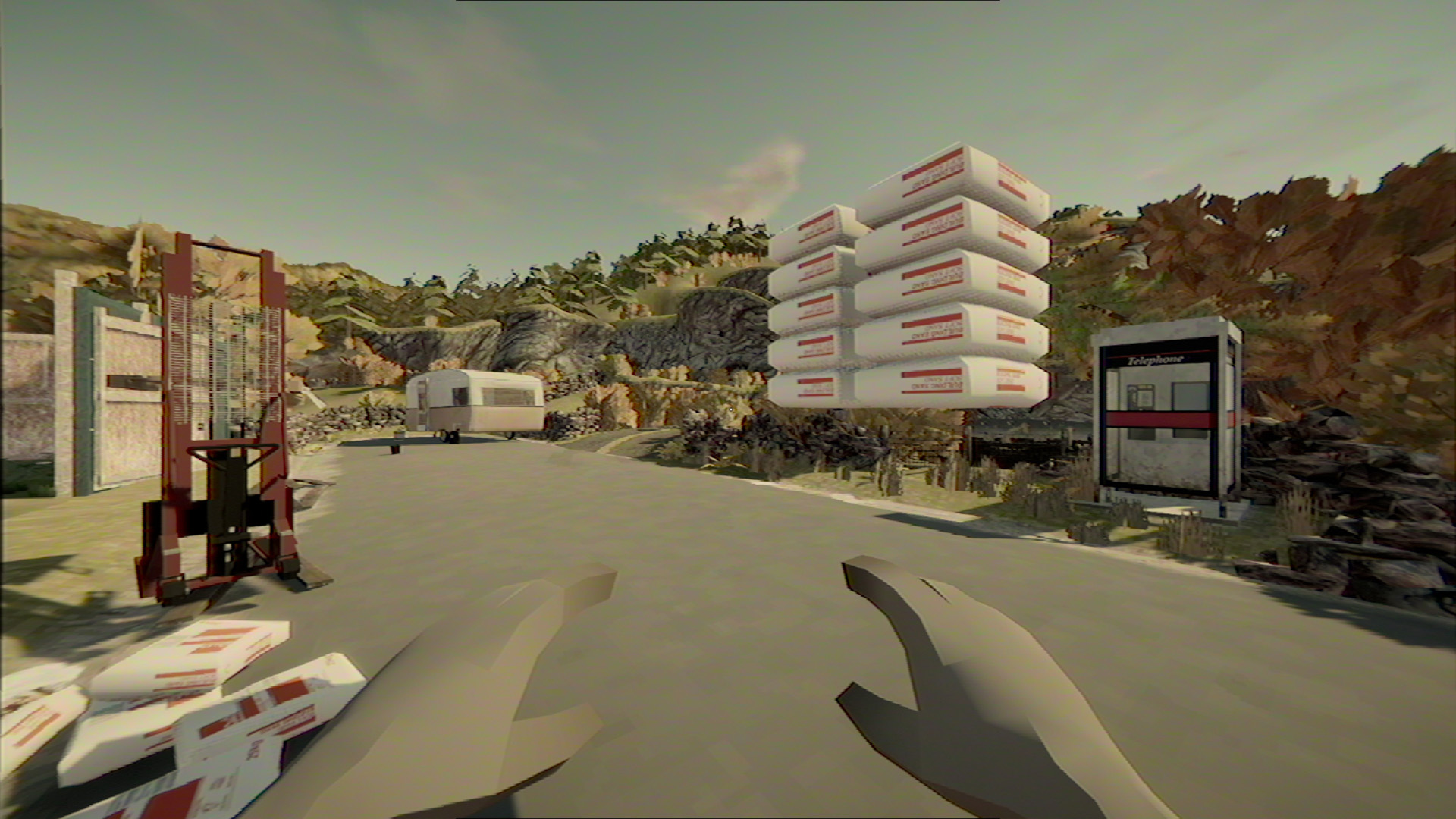

The sights of Sheffingham – limited in this version to just a couple of tool shops, a job centre and a pub, overlooked by an authentically depressing row of terraced houses – are a short walk or a bus ride away. Early on, you’ll sprint in and out of town with your trusty wheelbarrow, earning cash by washing pots at the local pub until you’ve enough spare coins to splash out on a bus fare on top of your building materials. Once you’re a little more flush you can call in new supplies using the classic British Telecom phone box outside your caravan, which summons a flatbed truck to be unloaded by hand or, if you saved up the cash to afford it, using a fun little ride-on forklift machine.

It’s around this point, just a few hours into the renovations, that you’ll have exhausted everything there is to do in the early access version of the game. New jobs stop appearing at the job centre, the locals run out of things to say to you, preferring to stare into the middle distance with vacant expressions, and Sheffingham starts to feel a little too much like the inert graveyard towns it’s so artfully depicting.

This version is riddled with some fairly serious bugs too, game-breaking cracks you could fit your entire fist into. Stuff vanishes into thin air, tasks don’t register as complete and your character tends to involuntarily phase through walls and slide up ladders like a greasy poltergeist. At one point I emptied a bag of cement so thoroughly that every bag of cement in the entire game became empty and the concept of cement simply ceased to exist. It’s not possible to recommend Landlord’s Super in its current state.

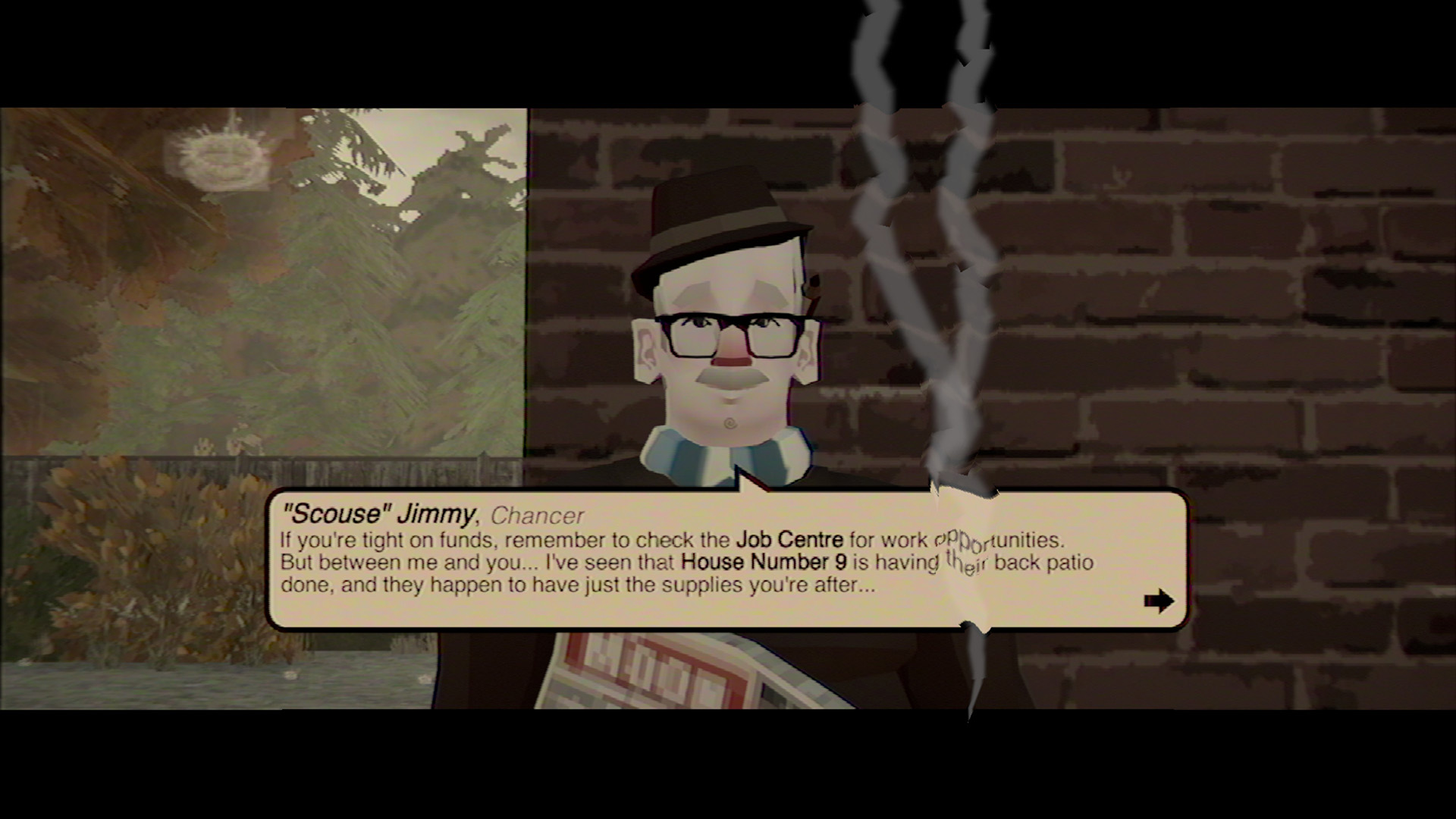

Future versions could take things in an interesting direction, one in which players might chart a course through the home renovation according to their own political and moral compass. The makings of this can already be seen in the handful of opportunities to pilfer building supplies from unwitting Sheffingham residents rather than buy them from the tool shop. For now stealing things carries no consequences besides a few lines of sad dialogue from the victims, but there’s plenty of scope for your behaviour to shape a developing reputation in town.

Landlord’s Super would be well served by expanding Sheffingham itself, adding more dimensions to the city’s shuttered high-street and grim local boozer to build on the game’s uniquely oppressive atmosphere. Because counter-intuitively, this depressing portrait of British urban decay is full of a hidden warmth and humour that makes it a pleasant place to hang out. We just need lots more of it, please.