Making of: System Shock 2

[Since it's Space Week, it's a good time to pull my Edge-commissioned Making Of System Shock 2 feature out of Stasis. The material for this was drawn from the lengthy conversation I had with Ken Levine last year. So, yes, before Bioshock. I'm quite fond of this piece, if only as it reveals the secret origin of the Psychic Monkeys...]

The lights are low. Everyone's panickedly fighting against a seemingly impossible, oppressive deadline. At every turn there's a crippling lack of resources. Viewed by any objective criteria, the small inexperienced team doesn't have the skills to achieve their aims. They're all crammed into a single room – in fact, half of one, since it's one room bisected with screens. When you look at where and how Irrational worked on their first game, it's easy to think of the claustrophobic horror of RPG/Shooter System Shock 2 as a pure product of its environment.

In fact, when looking at their situation in their early years, you begin to wonder why Irrational's co-founders of Ken Levine, Rob Fermier and Jonathan Chey splintered from Boston's illustrious and much-missed Looking Glass software in the first place. “Looking Glass was obviously a really impactful experience on me,” Levine says, “It was my first job in the games industry. I'd met a lot of people who I really respected and admired – people whose legacy is more known to the intelligentsia of the gaming field, and is still being felt. I left because despite how talented the people were there, in some ways it more like a university than a games company. There really was a dialogue about advancing the media, but not a lot about making successful products.”

Coming from a film-industry background, Levine felt they needed to find a balance between art and commerce. “I thought – probably naively at the time – Hey! I can do that,” Levine says, “I had no idea what that would actually mean, as I was a cocky guy who thought it'd be easy. We went off on our own and very quickly found it was challenging.” Almost fatally so. Their first project, a single-player version of early isometric shooter Fireteam had been canceled, when its publisher decided to concentrate solely on multiplayer. This left Irrational at a loss, until Paul Neurath, head of Looking Glass, called them with an opportunity. While they'd left Looking Glass, they were still on good terms with their previous employers. In fact, their half room was actually buried in a corner of the larger company's studio.

Neurath's offer was incredibly open. Looking Glass had, in developing Thief: The Dark Project, developed their own in-house engine. All of Irrational were experienced with it, having all worked on Thief. Why not make a game with it with us? Any game you fancy, really. “We immediately started designing,” Levine says, “The three partners sat down, and we ended up with a game design which was basically our design for Shock 2, but in a totally different world. It was a kind of Heart of Darkness story, with a military commander gone crazy and your mission was to go to this crazy space-ship and assassinate him.”. This was pitched around various publishers. The one who bit was Electronic Arts, who – through their purchase of Origin – were the possessor of the System Shock IP. They suggested that the game could, in fact, be System Shock 2. “And we said... um... sure,” Levine laughs, “I rewrote the story and changed a few of the things, but the game design never changed.”

It was a rare opportunity. The original System Shock was one of the games which made Levine want to move into the games industry in the first place. What made it so special? “The feeling of being in a real place,” Levine says, “The feeling of a mystery, of unraveling it – not in an adventure game way, but in the context of an action game. You arrive and... what happened here? That's a really good storytelling mechanism.” Austin Grossman and Doug Church original idea from Shock was something Irrational expanded in their sequel. “In Shock 1 you were a specific guy, so had a backstory,” Levine says, “With Shock 2, I really started you out with the classic “you wake up with amnesia”.”

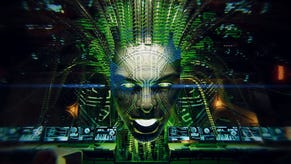

Abstract techniques and settings weren't all the Shock license gave them. It gave Irrational access to one of videogames' most startling antagonists, the hubristic Artificial Intelligence SHODAN. In the first System Shock, she frustrated and mocked the player at every turn, a rare case of the primary antagonist in a videogame being an almost constant presence. “My job was to try and work out how to present SHODAN in a fresh way to the player,” Levine recalls, “They've encountered her in the first game, and if she just says the same things she did then in the second, why is it Shock 2? Why isn't it Shock 1.5?” The resulting notion was to team up SHODAN with the player as an ally. An uncomfortable, prickly ally, but an ally nevertheless. “That was pretty daring for the time,” Levine talks of the initial appearance of SHODAN, “Villains only appeared in cut-scenes, do their thing and then disappear when you jump on their head three times. It was really fun to try and do something a bit more sophisticated. That twist at the beginning- even how she was introduced to you – was an important part of continuing her character and making sure the player knew what they were dealing with.”

In the working partnership with Looking Glass, Irrational provided the design, art and programming, while their old company provided the Dark Engine's technology base and the services of their Quality Assurance team. Looking Glass also provided other talents, including their Sound maestro Eric Brosius, (who has been involved in everything from Thief to Guitar Hero). His work on System Shock 2 is particularly memorable. “One of the reasons he creates such powerful soundscapes is that he creates a soundspace which has a bit of ambiguity to it,” Levine argues, “You can't identify every single thing you can hear. Sounds, voices, things people are saying, things you can't hear that are of unclear meaning.... That creates a great deal of tension. It adds another element of mystery, another element of suspense.” Sound is undoubtedly one of System Shock 2's highpoints, with Designer, Writer and wife of Eric, Terri Brosius reprising her role as SHODAN, sitting alongside a host of memorable roles, from mutants to robots to... psionic monkeys?

The latter, while one of the most fondly remembered of the game's cast, were actually an fortuitous accident. Finishing a motion-capture session two hours early , Levine was bullied by Jon Chey into just doing something to justify the time they'd paid for . “So I said [to the motion capture actor]... do monkey motions,” Levine says, “We had no monkeys in the game but we did it anyway”. These assets had to find a home, and Levine hit on the idea of lab-experimented apes, gaining sentience and being justifiably annoyed about their treatment at their hand of man. “All those story elements we had to back-solve. I find I tend to write best in those situations, when I have a constraint set already.” Levine says, “I have these psychic monkeys... so I had to work out how and why, in a way which wasn't ridiculous and hopefully kinda scary. When my back to a wall, I tend to work better”. Not that everyone saw the appeal of Psychic monkeys originally. “Everyone else was “Dude – you're fucking insane. We're not having monkeys in the game”,” Levine laughs.

That was about as easy as the development got. Every element was problematic. “No time. No money. I had no experience,” Levine states, “I'd never shipped a game before that.” In fact, of the three founders, only Chey had actually done so. “I think that only one or two people on the /team/ had shipped a game before,” Levine says, “That was a blessing and a curse. We had no idea what we were doing in some ways, but we also had no idea what we couldn't do. That's why the game feels innovative to some degree, as we were figuring it out as we went along.” It wasn't just the team that was inexperienced. The Dark Engine itself was far from finished technology, as Shock 2 was well underway before Thief came out. “It was still pretty broken,” Ken says, “It ended up giving us a lot of powerful things, but it constrained us in a lot of ways.” For example, the oft-ridiculed low-polygon models were resulting from having to make a conservative guess of what the engine would definitely be able to manage and still be playable. There was also some misplaced effort, in creating the co-op multiplayer which was patched into the game post release. “It was a real distraction,” Levine laments, “There are a number of people who really enjoyed it but the amount of time versus the amount of reward for that versus what we could have done on the rest of the game... I don't think it was a win. The single player game would have been much, much, much more stronger if we had that time back.”

Not that it hurt Shock 2's critical standing; despite slender sales (“I don't know the exact figures, but It certainly wasn't a blockbuster.”) its only grown in people's minds since, a key influence in people's anticipation for Irrational's Bioshock. “When I first did it, people would just look at me unless they were the intelligentsia of the intelligentsia of the game industry,” Levine says, “But now there's so many people who know it. I'd imagine if the game was still available commercially, it'll still be selling at this point. It'll probably have doubled in sales – and would probably have been a small success at that point. It may have made money because it was so cheap to produce.”.

Away from the matters of its financial performance, in terms of why it lingers in the imagination, Levine settles on the immaterial. Despite all the problems of its development, Shock 2 engaged with the imagination. “I think it has an atmosphere. Not a lot of games have atmosphere, and that really draws people.” Levine argues, “It's not a Lord of the Rings atmosphere, and I think people are drawn to that.”