Of grimoires and glyphs: the history behind RPG magic

Scroll for more

Imagine you’re on a quest for a powerful artefact in Divinity: Original Sin 2. Perhaps you conversed with a ghost who pointed you in the right direction. Now you see demons close by. You cast Chameleon Cloak to try to sneak by, but alas! you are spotted. The fight begins. You draw your weapons, inscribed with runes. You weave protective spells. You summon your cat familiar to enter the fray and confound your enemies. A fireball scroll sets a puddle of oil ablaze, but you misjudged and now you’re on fire as well! But a potion you concocted earlier heals your wounds just in time.

It’s a typical scenario for D:OS2 and similar fantasy RPGs. Magic is everywhere, and you could barely swing your cat familiar by the tail without hitting a fellow Sorcerer (don’t do that though, it’s cruel). But where do these spells, demons and artefacts come from? Games have so inundated us with magic that it’s easy to forget that even the most outlandish, videogamey spectacles have their Source-drenched roots in historical beliefs and practices.

Let’s take the elemental magic which has become a staple in most RPGs: geo-, hydro-, aero- and pyromancy. Ever since the ancient Greeks, the four elements of earth, water, air and fire were believed to possess mystical qualities. In classical cosmology, they comprised the innermost four spheres of the cosmos. All four elements were also used for divination (manteia in Greek, hence -mancy). This meant shapes in the soil, clouds, flames or ripples in the water were observed to gain occult insights or to see the future; perhaps a subtler form of magic than tossing fireballs or ice shards at your enemies.

Still, control over the elements wasn’t beyond the skill of “real” magicians. In the Early Modern period, witches were believed to cause hailstorms and lightning. Several centuries earlier, peasants were terrified of so-called tempestarii, who extorted money in exchange for not blasting their fields with supernatural storms.

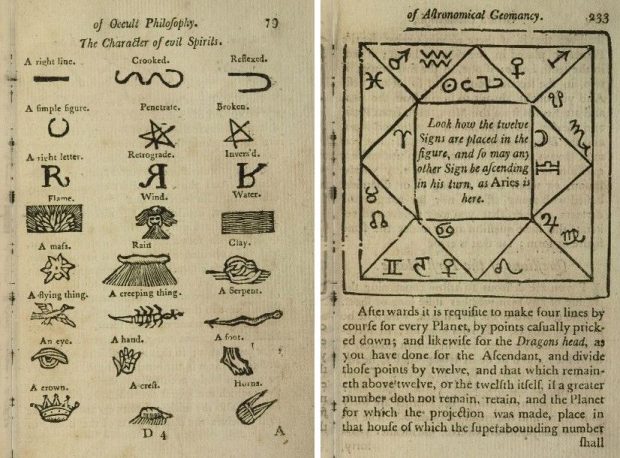

Characters of evil spirits (left) and geomancy instruction (right) in Henry Cornelius Agrippa’s Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy (1555)

All kinds of divination were often eyed with suspicion or even open hostility, but none more so than necromancy. Originally, necromancy referred to the summoning of the spirits of the deceased to interrogate them. In the later Middle Ages, necromancy was conflated with nigromancy, meaning black magic. Its very real practitioners, notoriously often educated priests and monks, attempted to summon and subjugate demons to use their supernatural powers for their own ends. In England, witches were believed to be accompanied by familiar spirits or demons in the form of black cats, toads or even flies. All these shades of black magic can be seen in Divinity: Original Sin 2. You not only get to summon your very own demons and familiars, but can even use your Spirit Vision skill to speak to the dead and find out about their deepest secrets.

Characters of spirits, Book of magic, with instructions for invoking spirits (ca. 1577)

But what would a ritual magician be without their grimoire? Such collections of spells, recipes and conjurations have been known since ancient times. Since their creation, use or possession was generally frowned upon (see ‘burning at the stake’), and they were often attributed to long deceased or mythical figures like King Solomon, Moses or Hermes Trismegistus, who were in no position to deny their involvement. Also, bygone ages and “mystical” places like Egypt were always thought to have been more magical than the here and now. Interestingly, Divinity does have its own wizard from antiquity in the infamous Braccus Rex, whose arcane knowledge in turn came from even more ancient wizards.

It’s a shame that D:OS2 doesn’t feature grimoires more prominently, but it does present a plethora of magic scrolls, occult manuscripts and skill books. The crafting section for creating scrolls is called “Grimoire”, and there’s some justification for this, as individual spells and glyphs from grimoires were frequently copied on pieces of paper or parchment to be carried around and used as charms. Some healing spells had to be ingested on a piece of paper to take effect. Those glyphs and spells were thought to be effective even if their meaning couldn’t be understood by the user.

Some scripts, like Malachim or the Alphabet of the Magi, both derived from Hebrew, had a magical aura independent of their content. In Scandinavia, runes played a similar role, and this idea reached games like D:OS2 in the form of collectable rune stones that infuse your items with special powers (some older RPGs like Ultima Underworld or Arx Fatalis made rune-like glyphs a central ingredient in their magic systems).

Speaking of crafting and DIY magicks, grimoires sometimes instructed readers how to create their own magical artefact. The most notorious of these was certainly the Hand of Glory (described, for example, in the 18th century grimoire Petit Albert). The Hand was created thusly: First, take the severed hand of a hanged felon, dry and pickle it. Then make a candle from the fat of a hanged felon and place it into the hand. It was said that a thief carrying the Hand of Glory would never get caught, as it rendered everyone they encountered completely motionless.

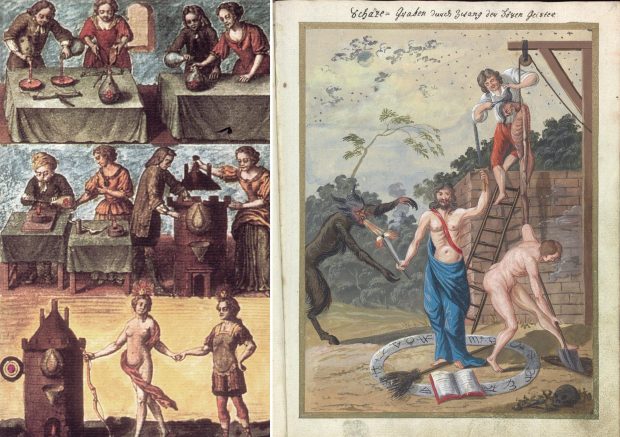

Left: Hand of Glory in the Petit Albert (18th century). Right: Demon with glyphs, in Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae (ca. 1775)

Other morbid artefacts include objects possessed by spirits or demons. It’s a popular trope, and D:OS2 features, among other things: a demon sword, a genie’s lantern, so-called Soul Jars, and a cursed ring that houses some part of Braccus Rex. Belief in such objects was very real in the Middle Ages. In a posthumous trial in the early 14th century, for example, none other than Pope Boniface VIII was accused of conjuring demons by means of a magic circle and animal sacrifice, and of possessing a ring that contained an evil spirit that acted as his advisor. Boniface would be mentioned several times in Dante's Inferno, as a Pope destined for hell.

But what about that healing potion you just used to swiftly heal your third-degree burns? Brewing potions is another staple of RPGs, and most, like The Witcher 3, conflate the idea with alchemy. However, this connection is tenuous. Alchemy was mainly concerned with the transmutation of metals and the creation of the philosopher’s stone - a mystical and complicated undertaking that is more concerned with the purification of the alchemist’s fallen soul than with the base creation of wealth or immortality.

Left: Crafting the philosopher’s stone in a few easy steps. Mutus Liber (1677). Right: Demonic treasure hunt, in Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae (ca. 1775)

Magic in RPGs is usually far more pedestrian than the lofty goals of alchemy. Divinity: Original Sin 2 may contain gods, a holy quest and a war on magic clearly inspired by real religious persecutions, but in the end, magic is mainly a tool to overcome challenges. And in this, RPG magic is surprisingly faithful to the ways magic has been perceived by most historical practitioners. Spells were supposed to bring health, wealth and worldly power.

One common purpose of magic was treasure hunting, for example, in the ruins of castles and monasteries (which were abundant in post-Reformation England). Spells were used not only to discover the treasure’s location, but also to drive away any demons that might protect the ancient hoard. In some ways, magic and adventure have been linked for hundreds of years and now they’ve come together in the form of your intrepid, insatiable band of adventurers, finally standing triumphant over the remains of your demonic foes, wresting the coveted artefact from their evil grasp. Keep this in mind the next time you poke your nose into ancient ruins in a quest for wealth and magical doodahs.

If you enjoy this type of thing, here are some of Andreas' reading recommendations:

Grimoires. A History of Magic Books, by Owen Davies

Religion and the Decline of Magic, by Keith Thomas

Europe’s Inner Demons, by Norman Cohn

Alchemy and Mysticism, by Alexander Roob