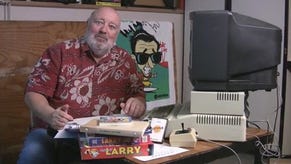

RPS Interview: Al Lowe

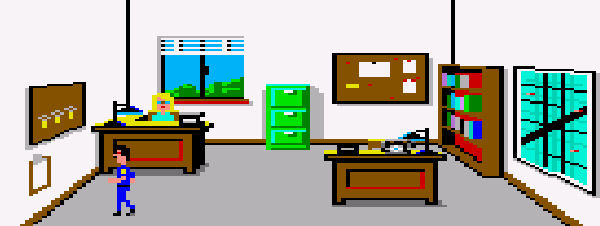

Anyone who grew up with games in the late 80s and 90s will be so very familiar with the name Al Lowe. Famous, infamous, certainly notorious, he was the creator of Leisure Suit Larry, a series of daft, entertaining, and ever-so-slightly naughty adventure games from Sierra. Lowe's credits go far beyond Larry, working on stories and coding for many of Sierra's seminal adventure series, but it will always be for the loveless lounge lizard that he'll be remembered.

However, in recent years the name of Larry has been somewhat spoilt. Sierra revived the series with the execrable Leisure Suit Larry: Magna Cum Laude, an astonishing exercise in bigotry. Lowe had nothing to do with it, his efforts now concentrated on his own website. With the news that Larry is to return once more in Box Office Bust (well, his nephew), we spoke to Al Lowe to get his reaction to the games. We also spoke about developing the original Larry and Police Quest games, the state of the industry then and now, why Lowe is no longer developing games, and some unique insight into the reason a generation grew up solving puzzles.

RPS: The Discovery Channel’s Rise of the Videogame said that Larry was the first game to be set in the real world. Do you think this is true?

Al Lowe: Gosh, it seems unlikely. But I’ll say this: it certainly was uncommon at the time. All the other niches were so full, there were so many swords and sandals games, and so many space games, and so many apocalyptic future games, that I thought something was missing. And it gave me a chance to poke fun at modern American trends.

RPS: Police Quest one was also 1987, which were two very starkly different approaches to the real world.

AL: Yes, I’m proud to have worked on both of those games. When Larry shipped, it had the worst sales of any product Sierra had ever released. I figured, well I’ve wasted six months of my life since I didn’t take any advances, just royalties, to get a higher royalty rate. I figured I’d better do something and they needed help with Police Quest, so I leaped over onto that team and did a lot of writing and a lot of re-coding… a lot of finishing work. I didn’t think much about Larry – I just assumed it had been a waste of time. But Larry’s sales increased exponentially, doubling every month.

RPS: Why do you think that was?

AL: I think it was a different game – a little bit adult, a little bit risqué, plus it was funny. People hadn’t seen anything like it. People told each other about it and word got around. Ken Williams was looking for where the audience was not, as opposed to today’s publishers who refuse to do anything that’s not already on the shelves.

RPS: It was an amazing time for exploring the possibilities.

AL: Yeah. Jim Walls [the police officer who co-wrote the games] had never written anything longer than a police report, but he had great stories to tell. Ken happened to be playing racquetball with him when Jim started regaling him with great tales of his highway patrol days. Ken said, “You should write a game!” Jim had just retired from the force after an incident where a perp came up to his car windshield, pointed a big .57 magnum pistol, aimed it right through the windshield at Jim’s face and pulled the trigger. All Jim could think of was, “I can’t get my damned seatbelt undone!” Fortunately, the gun mis-fired. But Jim had had enough and retired. So he had time to play racquetball, and then he wrote a game.

RPS: Those games were deadly serious.

AL: Jim was a stickler for police detail. He required every step to be precise. He wanted to make sure you felt that you couldn’t make a single mistake.

RPS: You’ve said that in the early 90s it was easier to develop than in the late 90s. Ten years on, do you think development has changed again?

AL: I would have to say it’s a mixed bag. In some ways it’s much, much harder. 3D characters, 3D levels, and particularly high-res design, are not twice as difficult to develop, but more like a factor of ten times. Games are afraid to break new ground because they’re so expensive to develop. Nobody wants to take a chance on a Police Quest or a Larry kind of game if it will cost them millions of dollars. They don’t know if it will sell. It’s much easier to do something that’s worked before, and just improve the graphics. But that’s becoming an increasingly smaller niche. The Wii has proved the point. People don’t care that the graphics aren’t hi-res, they don’t care that the angle of the character’s foot doesn’t match the 15° angle of the slope of the ramp he’s standing on, they like the gameplay. I think the average player – not the average game fanatic – but the normal gamer, cares more about gameplay than graphics.

RPS: Do you feel inspired by the Wii and DS as a designer?

AL: Not so much the DS. To me, it’s almost a throw-back to the old days. The two screens are cool, but the resolution and the capacity of the games is a big step back. I see it more as something nice to take with you somewhere, but it’s not the machine I would want to shoot for as a primary platform. But the Wii is. There’s a whole world of comic possibilities that haven’t been tapped yet with that machine. I wish that I were designing games again so I could!

RPS: So why are you not designing games again?

AL: A couple of years back, I worked on a game called Sam Suede: Undercover Exposure. We developed a prototype and took it to every major publisher. They reacted like, “Oh, Al. Your games were some of the funniest I ever played!” or, “You’re the reason I’m involved in computers!” or “Larry got me into games and now I’m the vice president of a games company.” And then they saw the game that we developed, and they said things like, “Oh, it’s so different. It’s funny, yet it’s action-based.” And still, none of them would take a chance and offer us funding to finish it. After that experience, I figured either the business has passed me by, or I’ve passed the business by. I don’t know which. It was very disappointing.

RPS: It sounds like Ron Gilbert’s story, when developing DeathSpank.

AL: Yes, Ron and I had lunch a while back and discussed this very topic. It’s a pisser! I love Ron’s games, and I love his sense of humour. He’s a great guy. I hope it works out well for him.

RPS: Humour is such an under-developed aspects of games. I was thinking about the old Larry games, and the parsing system, compared to the barren single mouse interface of modern adventures. When you look at this now, does it make you despair?

AL: [laughs] Well, I did put the parser back in Larry 7. And a few old-timers loved it. But the majority of players never found it or tried it. We put a lot of effort into making it work and giving it some funny lines. My approach was to use the tools available. When we got a new function or a new feature, I would do whatever I could to exploit it for the sake of humour. When we just had a parser, I tried to come up with a lot of responses to incorrect inputs. When we had point and click, I tried to hide a lot of hot spots with funny messages. I never tried to break new ground with my games; I left that to others. What I tried to do was exploit the tools that were there to my best advantage.

RPS: Do you think the desire to be funny in the games was driven by being in competition with LucasArts?

AL: No, not really. There were so few games released back then that all of us looked forward to the next game coming out whether it was ours or a competitor’s. When Lucas released a new game, everyone at Sierra was excited because we had a new game to play! It was a quite different then. We go a month or more between games you’d care about. For me it wasn’t about competition.

RPS: So what was the drive for you?

AL: I wasn’t a comedy writer, I was a high school music teacher. I had never written anything before I started writing games. I’d certainly never written anything funny. And I didn’t even know if I could be funny. But I knew that I had a sense of humour. I used to keep the students in my classes laughing. I had enough showman in me that I thought I could handle it. So I just threw in everything I could think of. I was afraid that people wouldn’t find some things, or they wouldn’t think it was funny. That’s the hard part about creating a humorous game. You develop the game so long before an audience ever sees it. It’s not like a comedy routine where you can go to a club and try it out, then tune it the next night.

RPS: I’ve noticed that we seem to have lost our patience with puzzles. Developers seem to be frightened of a player getting stuck. Why do you think this happened?

AL: I have a definite thought on this. I hesitate to share it as I don’t want it to come out sounding the wrong way, but I believe that in the early 80s, you had to be ridiculously determined just to make those damned computers work. It was near impossible. Set high mem. Deal with QEMM. Customize boot up settings. Hell, I had a whole subdirectory full of autoexec.bat and config.sys files…

RPS: [Large groan as the hideous memories came flooding back]

AL: … I would save off the current pair of files into a subdirectory and copy up another pair so I reboot, all just to run a game. I probably had ten different set-ups. Just geeky shit like that drove people crazy. So puzzle solving was a requirement just to get the damned things to work. And therefore puzzle solving in games fell right into place. It’s what you were already doing. And the parser? It was just like the DOS prompt. You got a flashing cursor and that’s all. If you didn’t know what to type, you had to try things until something worked. Our games were that way. The cursor would flash and you’d think, “What am I supposed to do now?” I remember a conversation once where we speculated, “Won’t it be wonderful when 10% of American households have a computer? Think how great sales will be?” Well, now it’s well over 50% and the people that we added aren’t the people who subscribe to Games Magazine, or solve New York Times crossword puzzles, or watch PBS or BBC America. They’re the people who watch Fox! Their demands for entertainment didn’t include slapping your forehead over and over while you tried to figure out what to do next. They wanted some action… and wanted it now!

RPS: So do you think trying to make adventure games today is futile?

AL: No, not futile, but not mainstream either. They’re not the majority audience as they were in the 80s. That same small slice of people who enjoy puzzle solving, being stuck, and figuring things out still exist. Of course, the Internet has hurt the puzzle aspect of adventure games. When you know that Google can find the answer to any puzzle, it’s very tempting to go take a look!

RPS: Do you follow the adventure scene closely now?

AL: Not seriously. I’ve moved away from the whole business. I work on my website, www.allowe.com, my daily joke list, CyberJoke 3000™, and I do volunteer work for non-profit web sites. CyberJoke 3000™ is nine years old now. I send out two jokes every weekday morning, so people can start their day with a smile. If you enjoyed the humour in my Larry games, you’ll enjoy the website. There’s some risqué stuff there, but there’s nothing pornographic, filthy, nasty, ugly or racist.

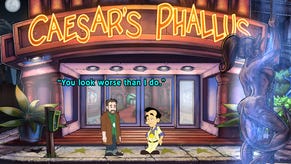

RPS: Talking of pornographic, filthy, nasty, ugly, and racist, let’s move onto Leisure Suit Larry: Magna Cum Laude.

AL: Nice segue! [laughs] I’ve said before, it was like getting a videotape from your son’s kidnapper; on the one hand, you’re glad he’s still alive, but on the other, my God, look what they’ve done to him!

RPS: Looking back, a couple of years since it came out, what are your thoughts?

AL: I would have thought they would have called me before they started the next one. Unfortunately, they didn’t. They’ve announced a new game that will be released in a year or so. It’s got to be better than Magna Cum Laude, right?

RPS: You’d think.

AL: But I have nothing to do with it.

RPS: When MCL came out, I gave it 3% in PC Gamer. It was just sickening. If anything, it highlighted how much better the original Larry games were…

AL: I guess in a way it was a compliment. It proved that what I did wasn’t that easy.

RPS: It made me realise how much those early games were on the side of the women.

AL: Well, that was always the case with my games. How do you take a chauvinistic arsehole of a guy and make him likeable? I solved it by making him think he was cool and on top of things, but then to make him lose. The women in the games always came out on top.

RPS: However, that’s not the case any more for the Larry series.

AL: No, not with Magna Cum Laude. It irks me that I had to pay full retail price for that game at a store. They didn’t even bother to send me a review copy! I guarantee you: I wish I had my thirty bucks back.

RPS: After the review came out, the publishers threatened to put the 3% mark on the box, to get revenge.

AL: I’d say you’re pretty close to my opinion. Part of it was the way they did it. They had a couple of Hollywood comedy writers write the scenes for the game a year before they finished it. They did their bits, threw it in the hopper, and left. They weren’t around to see how their ideas were implemented. Some parts were really funny, like the monkey with the British accent who was addicted to cigarettes. I would have been proud to put that scene in a game. But then there was so much more that was, just, what were they thinking?

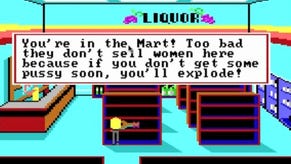

RPS: The scene that stands out for me was when you’d strap a dildo to a teddy bear, then use it to… well it seemed like rape, to me, a psychologically disturbed woman.

AL: Yeah! What the fuck? The game was almost schizophrenic. There was one side which was interesting humour, then there was this just weird stuff. For instance, Larry would walk up to a girl on campus and say some kind of smarmy line, something like, “What would look good on you? Me!,” something fine like that. And then she would reply with, “Fuck off, cock-sucker!” What? WHAT? That’s the best you could do? And I never want to play “quarters” again!

RPS: I read an interview with the development team on the new Larry game, Box Office Bust, where they said they wanted to make a game that you would enjoy playing.

AL: If that’s the case, why didn’t they just have me design it for them?! Maybe they spent all their money on voiceover talent. People are supposed to ooh and ahh because they hired Carmen Electra. That’s not what makes good games. I bet they spent more on voiceover talent than I ever spent making an entire game. I can’t imagine what that list of talent cost them.

RPS: So given that you’ve said you’re retired, if that call came through and they asked you to make a new Larry game, would you do that?

AL: Well... [a long pause], I would certainly be open to it. But there are so many shades of grey between that statement and reality. Would I have control? What sort of deal would we make? But, assuming all that could be solved, hell, yes! I’d love to do another game! Part of the reason I hesitated on this answer, and qualified it, was because Ken Williams really spoiled me. I had total artistic control of my games and our financial negotiations were pretty much, “You want to do another game?” I’d reply, “Yeah.” and he’d say, “Okay. Have fun!” Very relaxed. I was totally in charge, and apart from reasonable budgetary restraints, I had enormous freedom.

RPS: Who knows, maybe the next one will be better.

AL: Well, my belief is it won’t be any worse!