Hands On: Shardlight

Rebellious

While the world got over-excited at the prospect of old men and women emerging from their dusty tombs to make adventure games again, one indie production company quietly continued putting out the best in the business. Dave Gilbert's Wadjet Eye diverged from his self-created Blackwell series to producing adventures made by other individuals or tiny teams. The results have been splendid games like Technobabylon, Resonance and Gemini Rue. While I've only played the first third, it's looking very hopeful we will be able to include Shardlight [official site] in that list of successes. The post-apocalyptic adventure from developer Francisco Gonzalez presents an intriguing story in an immediately embellished and believable post-apocalyptic world.

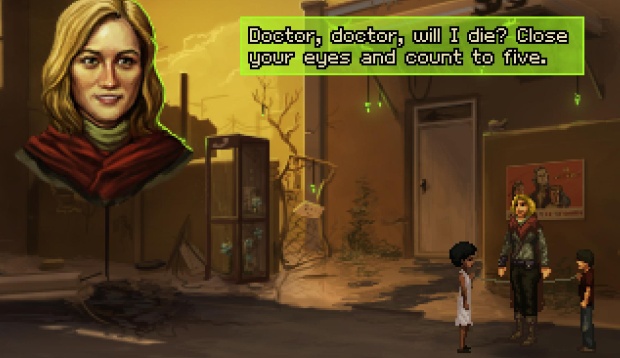

Far too often adventure games (and indeed any games) can spend much too long trying to force its exposition down your neck. LOOK AT OUR WORLD AND HOW IT'S DIFFERENT FROM YOURS! NO! LOOK MORE! KEEP ON LOOKING! Shardlight is a really rather splendid example of how to assume the player isn't an idiot, and can pick up on entirely obvious themes without having them screamed. This is a post-bombs-falling world, in which an authoritarian and oligarchical governance called the Aristocrats has risen to take advantage of the chaos. You play Amy Wellard, a mechanic who is forced to take on "lottery jobs" to be in with a chance of winning vaccine from the government to treat a wildly spreading plague that's infected her.

Lottery jobs are the kind of shitty tasks that no one wants to do. The game begins as you descend into a dingy under-street series of tunnels, tasked with fixing a reactor that generates electricity for the upper classes. Down there Amy finds a dying man who gives her a sealed letter, telling her if she delivers it then everything in her life will change. And so it does. It's a tale of conspiracy, underground rebellions, and torn loyalties.

From this point on, Shardlight keeps getting things right. I think this is best represented as a checklist of what these games normally screw up, and why Shardlight - in its first third at least - does not:

- Too many locations

It's a fine art, getting the balance of locations correct. Obviously it's just an escape-the-room if it's linear, but too often adventures give players an agoraphobic paralysis by giving them far too many involved places to go and not nearly enough direction. (Dropsy, I'm looking at you.) Shardlight gets this just right, with three or four places immediately available, each of them packed with people to talk to, alleyways to explore, objects to find and use, etc, and then rapidly adds new areas just when you're ready to move on.

- Over-simplified inventory puzzles

This is a modern curse of point-n-clickers, where the inventory puzzle has been reduced to putting the triangle-shaped object into the triangle-shaped hole, reducing any point in their existing in the first place. Where once poorer games would require you click everything on everything, more recently you click one thing in the only place it could go. Shardlight remembers how it's meant to work, with a small collection of items, and ways to use them ranging from sensible to esoteric. It also understands that it's great fun to have one object that accompanies you all the way through with multiple uses, which this time looks likely to be a trusty metal bucket.

- Brainless world puzzles

If you're an adventure designer and the words, "sliding tile" ever cross your mind, it's your duty to quit your job and work on an oil rig for the rest of your life. There are ways to implement more traditional puzzles into a point and click game, but ambitions can stretch beyond restoring a torn up note. Shardlight has some lovely examples of this, including a door lock puzzle that requires you do some in-game research in a book, then apply that elsewhere, in a very satisfying manner.

- Unrelatable characters

Amy is extremely likeable, without being perfect. She's reduced to performing dangerous jobs that don't use her skills because she needs to enter the lottery for a drug that will save her life. And most tellingly about her, she has a lot of friends all over the city, people who are pleased to see her, act positively toward her. Making them relatable too! While there is certainly unnecessary obtuseness from some, these are people willing to help her, positive around her, rather than grumpy or sullen or plain confusing. It is a fantastic shortcut for having you feel like you're playing an established character in an established world, rather than the all-too common memoryless avatar freshly emerged from a cocoon.

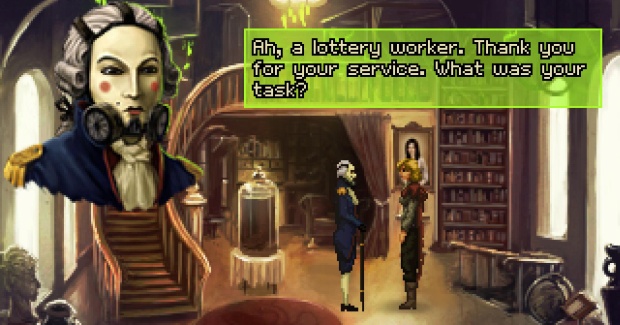

Add to that list some really splendid voice acting. Forget the olden days of Wadjet Eye's hissy, amateur voicework - this is really professional and naturalistic stuff. And then of course there's Ben Chandler's glorious artwork. I think this is his best yet, the portrayal of a conflicting society of extremes of wealth and poverty elegantly set in a broken world. Character design is lovely, the super-simple pixels of their animated forms managing to portray immense amounts.

The one thing standing in the game's way is, as ever, the engine. Wadjet Eye have previously promised they intend to move to Unity, and dear me it can't happen soon enough. Chris Jones' Adventure Game Studio served a wonderful purpose for years, but it's really wearing bone-thin. It seems now to be a technical restriction, clunkily making the gorgeous art of this game awkward to run at large sizes, rather than supporting these games in a useful way. The pixel art is marvellous, and importantly, artistic. But I'm pretty sure Unity could be bent and snapped in such a way as to present it in a far smoother, more accessible way. Still, it's just about good enough to let Shardlight shine.

I'm hooked by the story, especially because it hasn't felt the need to hammer home its finer points. I adore that the Aristocracy wear what look like porcelain masks, a grotesque assimilation of the powdered-white faces of the British Elizabethan era, and this is only mentioned once in a throwaway remark. There are lots of lovely details like this, world-building asides. The story reveal that occurs just before this preview version ends will be ridiculously obvious to anyone who's ever seen a film or read a book in their lives, but there's no real harm there. The tale is smart enough that it doesn't rely on such surprises.

But most of all, this was an absorbing puzzle adventure, which is a phrase all too rarely uttered even in these days of the genre's clumsy resurgence. I'm very much looking forward to March to continue onward, and rather hoping that it manages to maintain the standards, and not fall off a cliff (as with last year's almost good Dead Synchronicity). Only a couple of months to wait.