IF Only: Remembering Textfyre

An attempt to make commercial parser IF viable

For quite a lot of the 2000s, IF enthusiasts hoped for a future in which parser IF would become commercially viable again. There were various theories about how to do that, but one company made a more serious attempt than most. Dave Cornelson put together Textfyre, a company that would create interactive fiction aimed at roughly middle school-aged children. The games would have a custom interface that resembled a book, and they'd be released as parts of a series, to encourage repeat sales. There would be handmade maps and artwork, so that these games would feel like quality products. And they'd sell for a serious price, $25 each.

Another key feature of the Textfyre concept was that the games would not all be the product of a single creator. The vast majority of amateur parser IF was written by single individuals, though there are some honorable exceptions, pairs of authors who have repeatedly worked well together: Jack Welch and Ben Collins-Sussman, for instance, or Joey Jones and Melvin Rangasamy. Still, the vast majority of parser IF, including IF from the commercial era of the 80s, had a single person as writer, designer, and primary coder. Textfyre aimed to move away from that. There would be separate designers, writers, and implementers for every Textfyre piece.

In 2009, after years of discussion and preparation, Textfyre completed and released two games. Jack Toresal and the Secret Letter was first, a collaboration between Cornelson himself and the acclaimed Michael S. Gentry. Before Jack Toresal came out, Gentry was known for two horror games: the surreal office story Little Blue Men, and then the Lovecraftian Anchorhead, which came out in 1998 and has been pretty consistently considered one of the greats of the noncommercial IF canon ever since. The prospect of new work from Gentry intrigued a lot of people in the IF community.

The second Textfyre release was The Shadow in the Cathedral, a collaboration between Ian Finley (Babel, Kaged) and Jon Ingold (then known for the vast puzzler The Mulldoon Legacy and the creepy story piece All Roads, though he has gone on to create quite a lot else and to cofound inkle studios).

Jack Toresal and the Secret Letter didn't really take off as Textfyre had hoped; even within the IF community, the reception was fairly lukewarm. It probably didn't help that the game had to compete with a lot of freeware parser IF, and the price was more than some people wanted to pay.

But I'd guess a significant issue is the way both the storytelling and the gameplay are simplified to make the game suitable for young readers. Though this was a marketing decision on Textfyre's part, there was a broader trend ca 2009-2011 towards games designed to be playable by preteens and meant to be friendly to parser novices in general: see among others Matt Wigdahl's comp-winning Aotearoa (2010); Gentry's own non-Textfyre piece The Lost Islands of Alabaz (2011); Wade Clarke's Six (2011).

Different games handled this challenge with different degrees of grace, though. Jack Toresal deals with the prospect of younger players by avoiding both challenge and ambiguity as much as possible. It is highly linear and heavily sign-posted, with the characters rushing to tell you what you should do next, and many gameplay sections requiring no more of the player than the ability to move from one room to another. The main exception, curiously, comes right at the beginning: it starts off with an escape-the-guards puzzle that requires scampering around a slightly confusing map. But aside from that, quite a lot of the game consists of following NPCs around, doing what they say, and plowing obediently through dialogue menus.

Linearity isn't necessarily the kiss of death in parser IF, but the most successful linear parser IF offers the player some other juicy, turn-by-turn reward: jokes, suspense, the opportunity to at least interrogate the scenery. Jack Toresal instead underplays what might have been its most dramatic moments and underuses its interaction. Frequently when there's some critical action you must take, it makes those transitions automatic — for instance, the following is all a response to a single move:

>E

You peer across the gap at the balcony, judging the distance. About ten feet. Maybe a little bit more than ten feet. And it's slightly below you, which is a plus.Still, it's a really far jump.

This is where Bobby told you to go. A letter... secrets about your father, he said. The thought of facing Bobby when he gets out, after they beat him up so bad, and telling him you were too scared to do what he asked you to do...

You take a few steps back, run... and jump.

There's no opportunity here to contemplate the risk; no "are you sure?" followed by a confirmation. You're told it's too far, you're told you have doubts, and then your character jumps anyway. There's no tension here, no pause between the fear and its resolution.

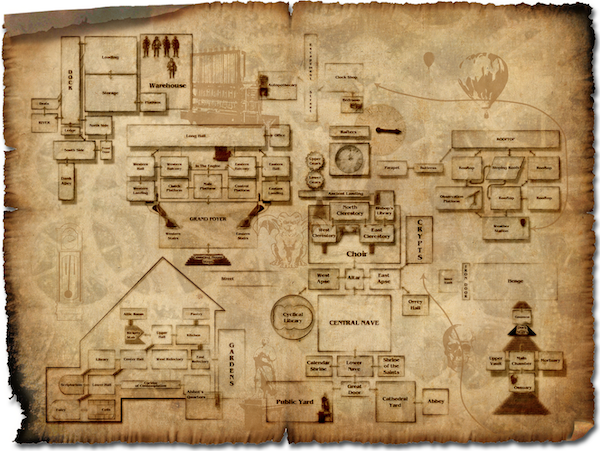

But my biggest issue with Jack Toresal is the story. The world, and the characters in it, are paint-by-numbers pre-modern fantasy. I kept changing my mind about what flavor of pre-modern: the plumbing and some furnishing suggests the 19th century. The money-lender characters are distinctly Dickensian, while the clothier is a gay stereotype imported from a sitcom ca 1995. Other aspects feel pre-industrial, weapons are blades rather than guns, and the Baron lives in a motte-and-bailey castle. (Which admittedly might just be extremely old.) The custom map, meanwhile, portrays several of its buildings as vaguely Tudor:

World-building is minimal: religion apparently involves the worship of goddesses, and there are a few gestures at the economy of this world, but it's all pretty thinly imagined. There's a dynastic struggle going on between a Duke (dead) and a Queen and a Princess and a Baron, but their entanglements don't carry any particular historical weight, any sense of actual power being negotiated under threat of violence. The characters pretty much fall into three categories, Bad, Good, and Greedy. The good characters generally like you from the start; the bad pretty much dislike you; the greedy will switch allegiance when convenient.

The prose is competent, and occasionally affecting — Gentry is a capable writer, and he hasn't forgotten his craft there. But it's hard to write really sterling material with such simple, un-nuanced characters and setting. The writing just doesn't have enough work to do.

That comes through especially in the conversations. There's just not enough there for these NPCs to convey, once they've let you know whether they are Good or Bad. Even in situations where they really logically shouldn't, they almost all tell you the literal truth. There are no lies, no hidden stakes, no subterranean agendas. One might (I suppose) say "well, that's because it's for young people," but if so, that underestimates the young: a lot of YA literature is in fact precisely about learning to read subtext and model other minds more accurately.

Then there's the protagonist herself, a girl disguised as a boy who lives in an orphanage but secretly has an important heritage. (In this world, all the female orphans are encouraged to dress as boys when they leave the orphanage, for their own protection. Institutionally-mandated crossdressing is a potentially interesting idea whose implications the game refrains from exploring at all.) Everyone except Jack/Jacqueline seems to be aware of her heritage, so you wonder how she managed to be oblivious to it this whole time.

Come to that, Jack is as free of personality markers as possible. Before her political enemies start trying to kill her, she doesn't really have much by way of an agenda or ambitions; and once that happens, she spends the rest of the game doing what other people tell her. Then the game ends in a huge cliffhanger because this is supposed to be part 1 of 3 and we want people to buy the sequels. (They were never written.)

So Jack Toresal I would tend to recommend primarily as a piece of IF history and an experiment in parser IF UI, unless you happen to belong to exactly its target demographic. The Shadow in the Cathedral, I'm happy to say, is a much, much better piece of work.

Like Toresal, it's young adult fiction, but it takes place in a stranger and more vivid world. Its action sequences, though often still quite directed, are punctuated with interaction at the right moments. There are a number of set-piece puzzles, not desperately difficult but with enough elements to keep even an adult engaged. And those puzzles are doing some narrative work, demanding that the player demonstrate an understanding of the game world and the situation.

Shadow begins thus:

When the monks took me, aged six months, into their care, they named me Wren. Maybe because I was small, insignificant, and happy to eat any crumbs they threw my way. But these days I'm Wren, 2nd Assistant Clock Polisher... and that's a role that's about as important in the workings of the Cathedral of Time as the large deaf man who re-stretches the worn-out springs.

This is a world decorated with busts of "St Newton," in which clockwork is holy. Many of your tasks require manipulating machinery of Rube Goldberg complexity. The Tea Maker is a thing of beauty. The NPCs participate in the clockwork nature of the universe as well, coming and going on a schedule. This fits the theme. Wren has an assigned place in this universe, but she's forced to deviate from her normal path, and then everything becomes more complicated.

The plot contains a lot of the same tropes as Jack Toresal: its protagonist is also parentless; she also overhears a conversation in the first few moves of the story; she too goes off chasing MacGuffins. But Shadow offers more freedom, and a character with more personal agency. Its protagonist speaks in the first person. Her ideas about what to do next are hers: the inner monologue stands in to provide the direction that comes from NPCs in Jack Toresal.

Finally, I suspect some of Shadow's comparative success comes from not dividing up the creative labor as many ways. Where Jack Toresal combines Gentry's words with a design and plot by Dave Cornelson and has a third party implement, the roles blended more in Shadow, where Jon Ingold did the programming as well as doing writing and some design. The interaction is sly, even witty, in ways that reflect Ingold's particular style as an IF writer — and his ability to make fine-grained changes in the timing and presentation of the gameplay. That might have been less likely had the writing, design, and implementation been parceled out to different people.

Like Jack Toresal, Shadow ends in a cliffhanger, preparing for a continuation that was never written. But it's quite a lot of fun even so. Had it been released under other circumstances, I suspect it would have been much more widely played, discussed, and admired. It is one of the best parser IF pieces of its year, and pulled in a number of nominations in the 2009 XYZZY Awards.

Textfyre has closed down, and both of Textfyre's games are now available for free on itch.io. If you decide to complete Jack Toresal, be sure to make some save files; I got stuck about four chapters in because the next section of the game was supposed to be triggered by visiting an NPC, but because I'd already been to see her, I broke the game's anticipated sequence and wasn't able to progress. I am not aware of any similar issues in The Shadow in the Cathedral — but there are enough challenges there that you'll probably be inclined to save occasionally anyhow.

[Disclosures: Emily has met Dave Cornelson, Jack Welch, Ben Collins-Sussman, Joey Jones, and Melvin Rangasamy. She has worked with Jon Ingold. More generally, Emily Short is not a journalist by trade and works professionally with various interactive fiction publishers. You can find out more about her commercial affiliations at her website.]