The Flare Path: Crosses the Pennines

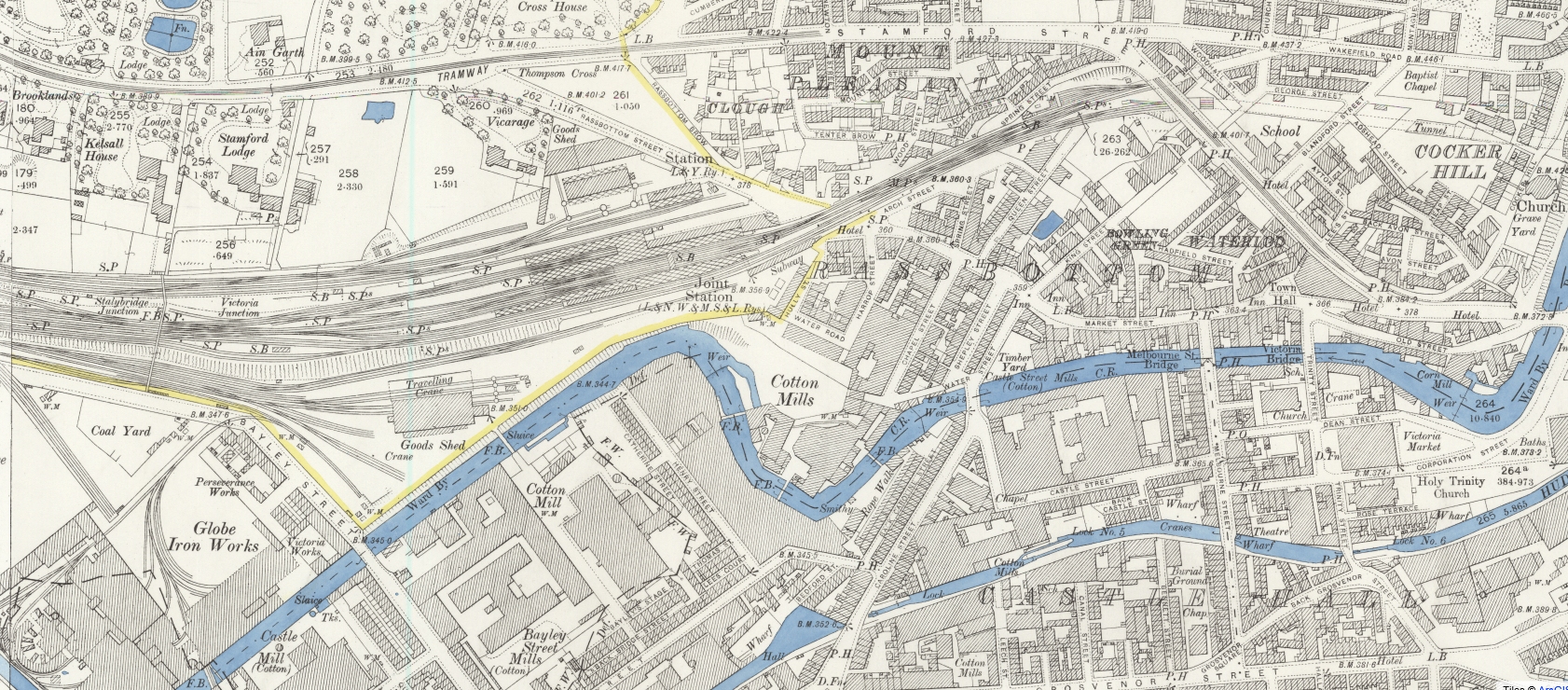

A Manchester-Leeds magical history tour

The last Flare Path Rail Tours Ltd excursion was such a 'success'* that I've decided to organise another. Once again Train Sim World will be providing the seats and scenery, and I'll be supplying the topographical trivia and light refreshments. At 13.30 on the dot the train now standing at Platform 16 of a circa 1982 Manchester Victoria will depart for Leeds via Huddersfield. Jump aboard for tales of incredible engineering, tragic explosions, vanished industries, and social unrest. Jump aboard for blocked WCs, overpriced sandwiches, and slightly disappointing rural vistas.

* Nobody died

But not before you've visited the UK's oldest public library! A stone's throw from Manchester Victoria is Chetham's Library, a book browsing facility that opened its stout oaken doors for the first time shortly after the end of the English Civil War. In 1845, the year when Parliament approved the Huddersfield and Manchester Railway and Canal Company's plans for building the line we're about to explore, proto-Communists Marx and Engels met regularly in Chetham's to pore over economics tomes, suck humbugs, and put an extremely inequitable world to rights. The latter's radical politics were shaped by first-hand experience of mid-19th Century Manchester's disease-ridden slums and dark satanic mills.

Dovetail haven't bothered to polygonise Chetham's but an equally venerable landmark to the north of Victoria has been simmed. Lean out of a port window as we trundle eastward through the station throat, and you may be able to make out the grey brick finger of the Boddingtons chimney. Over 200 years of brewing at this famous firm's Strangeways premises ended in 2005 and the elegant Victorian smokestack hung on for another five years before suffering a slow, piecemeal death-by-pneumatic-drill that must have made local steeplejack Fred Dibnah spin in his grave.

A few hundred yards short of another extinct brewery, Wilsons, we bear right, leaving the Oldham line for Ashton-under-Lyne. Miles Platting station occupied two sides of this triangular junction from 1844 to 1995 and, in the late 1980s, a young poet destined for great things immortalised its desolation in a poem that wends, as we are about to do, eastward across England's thoracic vertebrae.

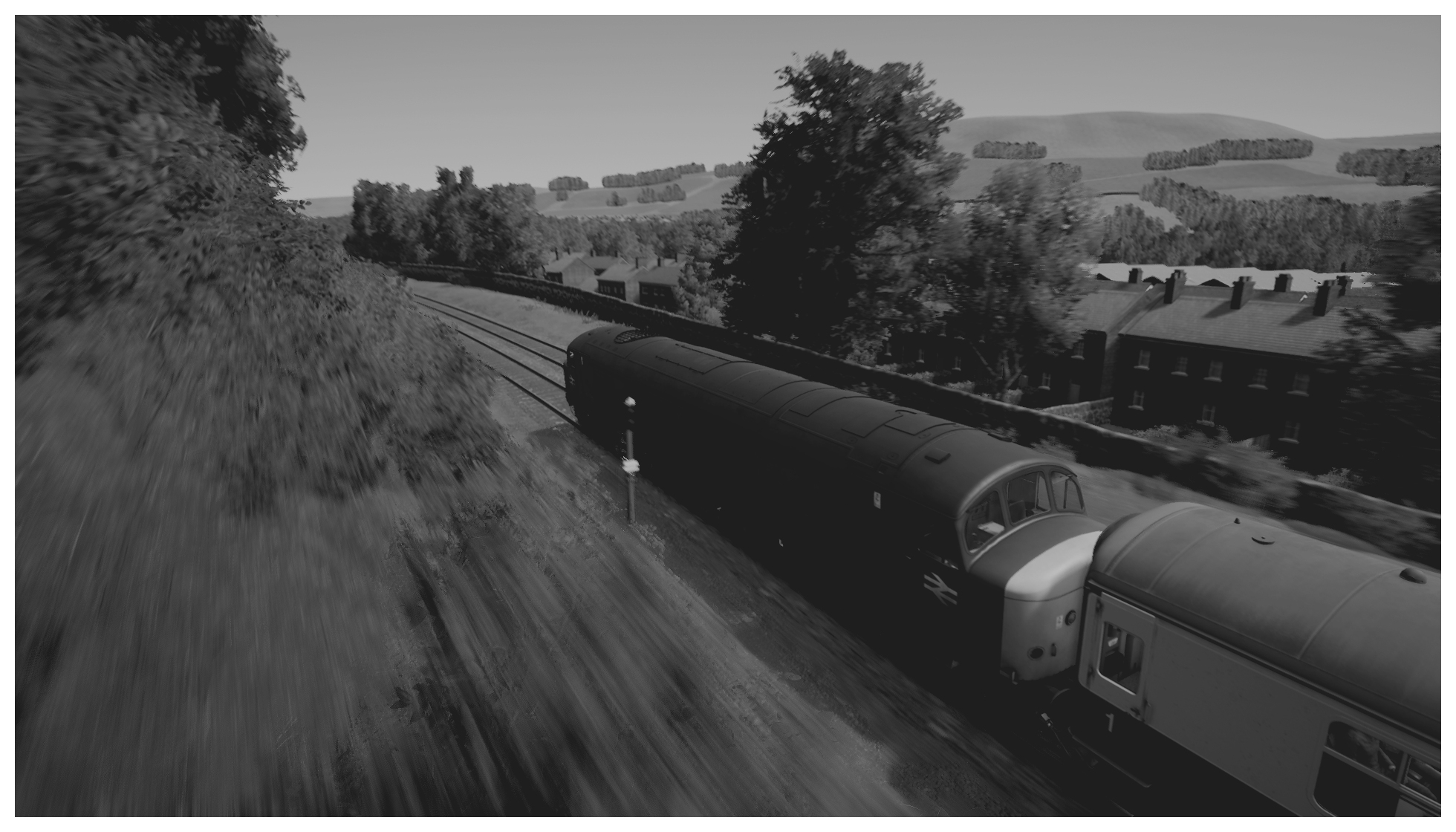

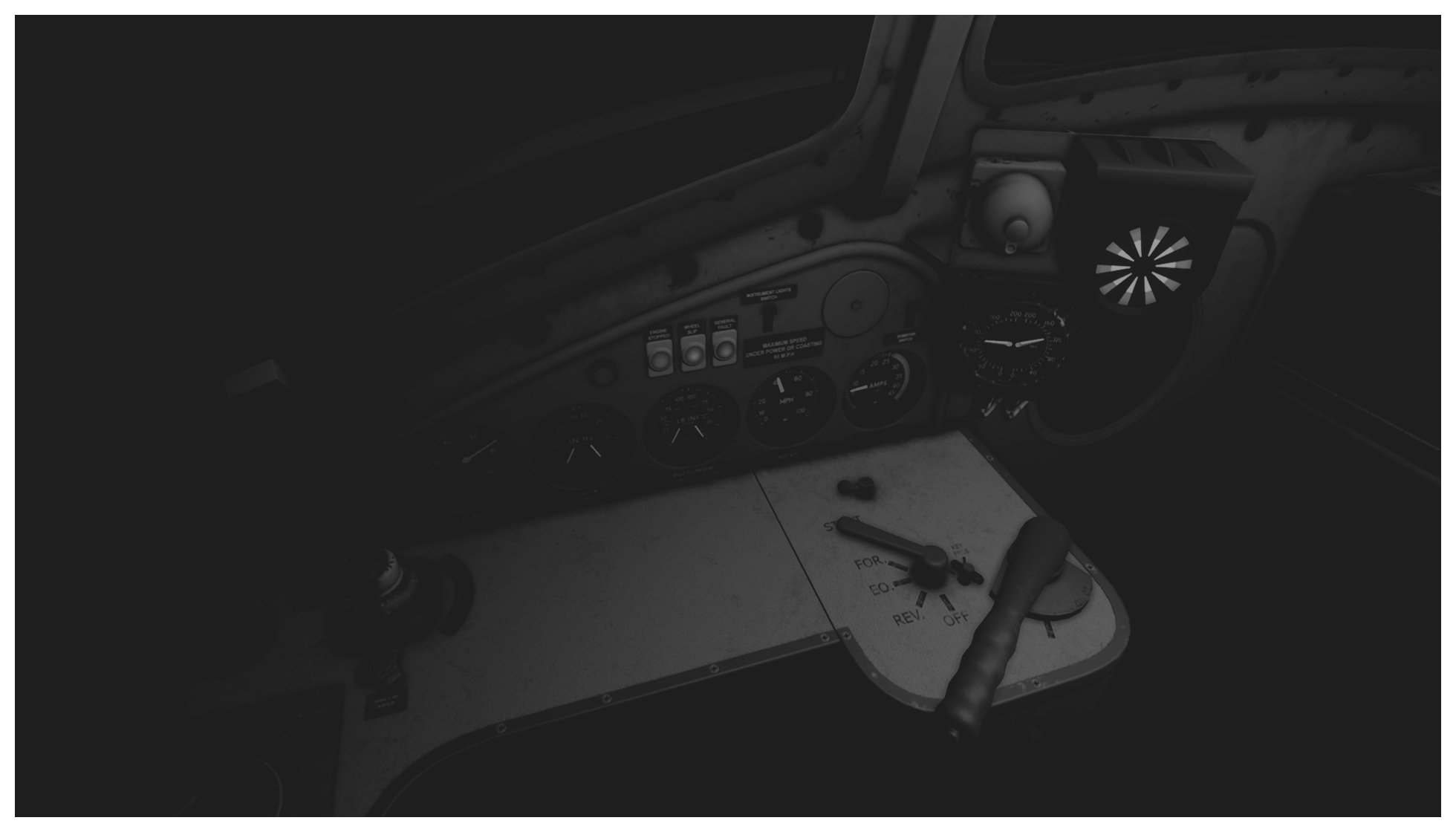

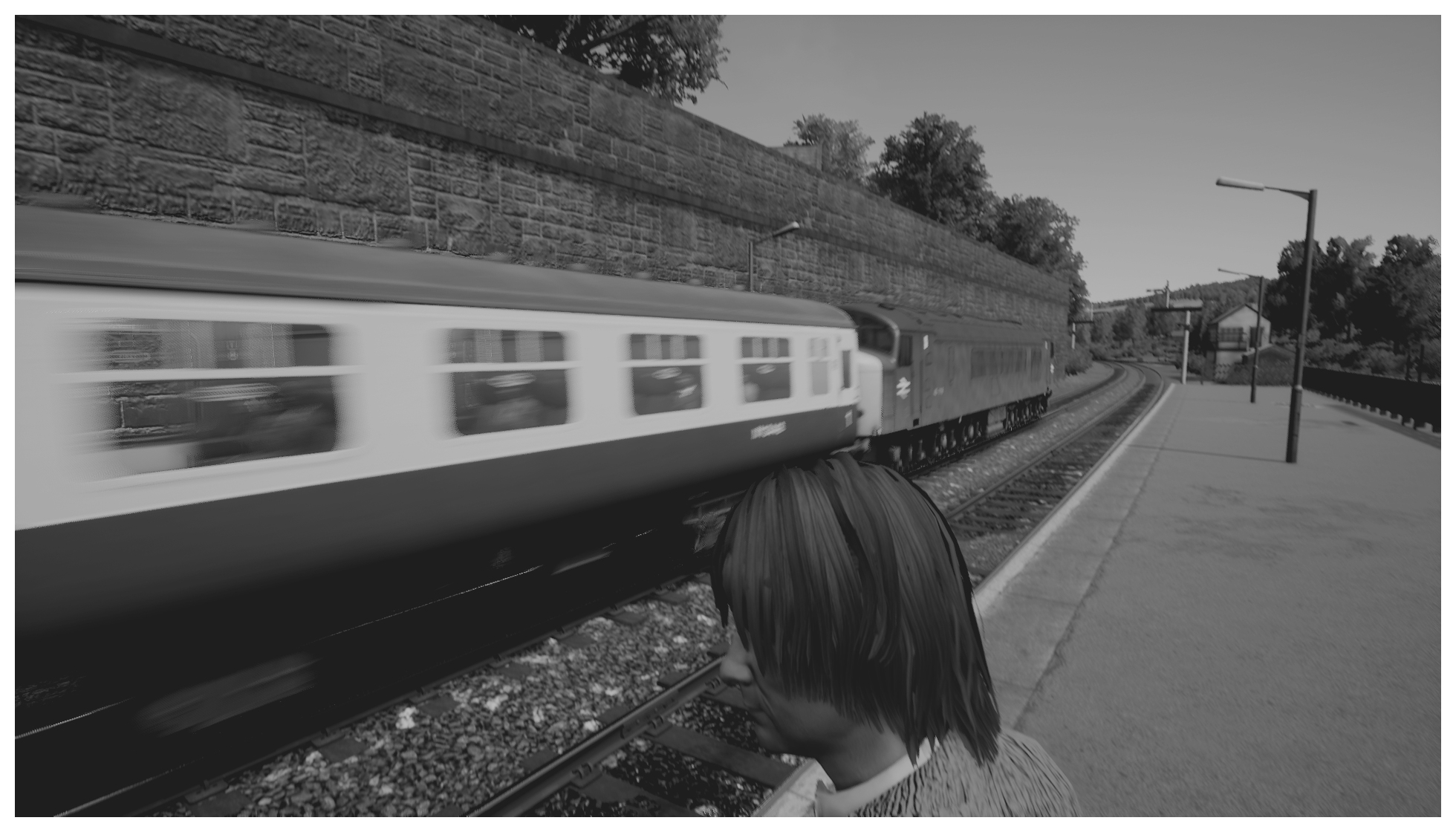

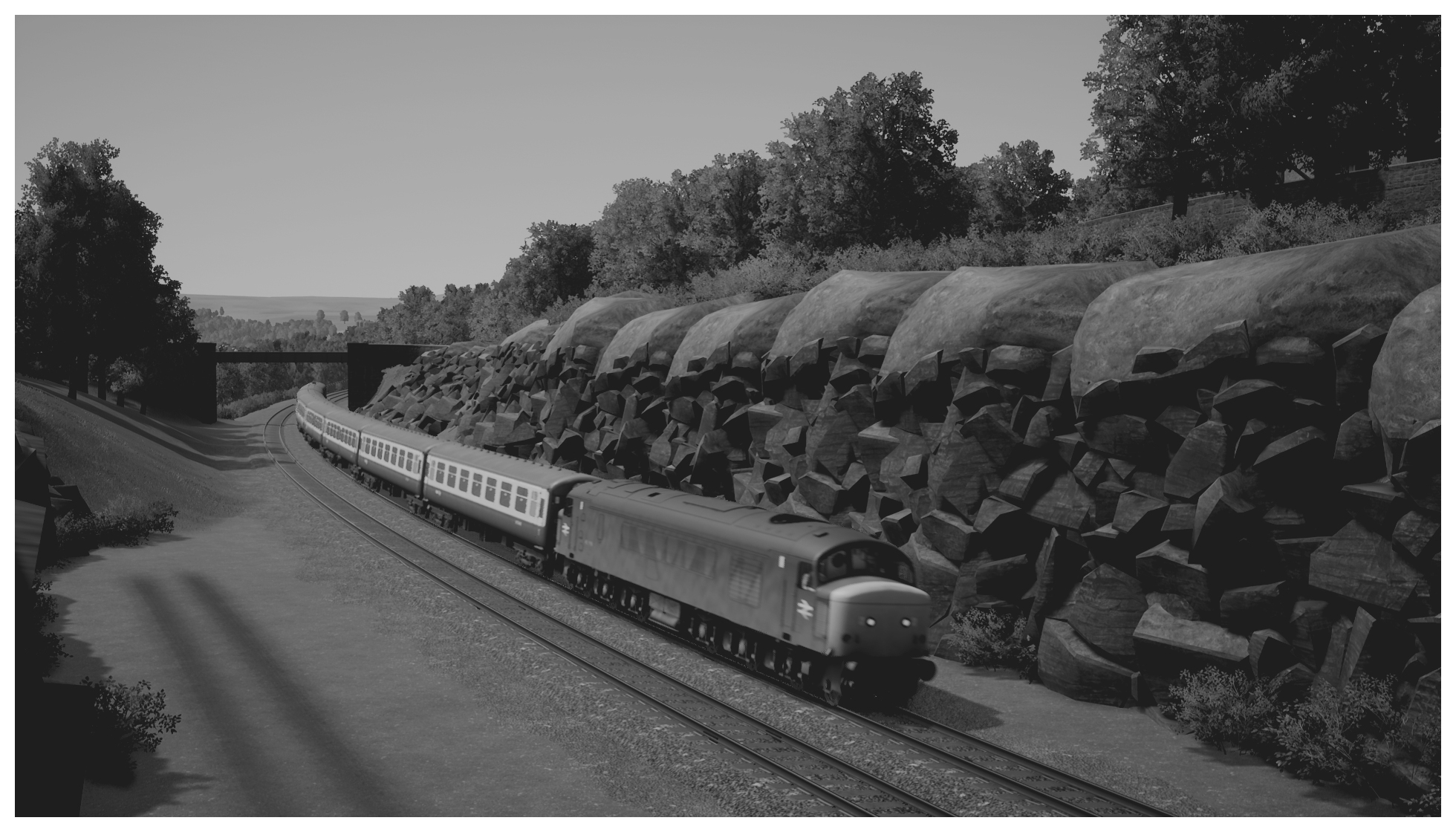

Hear that wonderfully guttural growl? That's the result of a fully opened throttle and Dovetail raising their game in the audio department. I've chosen a virtual 'Peak' for today's jaunt primarily because it sounds so splendid at maximum revs. The three rides (Classes 45, 47, and 101) included in this, the latest TSW expansion, all suit the route, look great and sound much better than I expected them to, but cabs reluctant to shake and sway, and the odd stretch of lifeless lineside undermine some of the sound gatherers' hard work.

We're now approaching the first of a series of river-hugging, canal-connected mill towns. Ashton-under-Lyne's story of rapid growth/industrialisation is fairly typical of the area. From an 1845 gazeteer:

“In 1775, the population of the town was only 2859; in 1801, 6500; in 1811, 7800; in 1821, 9222; in 1831, 14,671; and in 1841, 22,689. In 1750, the inhabitants were humbly engaged in spinning and weaving cotton by hand, in their cottages: in 1785, Arkwright's machines gave an impetus to the trade... At present there are in active operation within the borough, 77 large factories; and within a radius of two miles from the parish church are 160, of 5199 horse-power, consuming weekly upwards of 2,000,000 lb. of raw cotton, employing on the average nearly 23,000 workpeople”

Like many neighbouring communities, Ashton was knocked sideways by the Cotton Famine of 1861-65, a slump caused by overproduction, speculation, and supply disruption linked to the American Civil War. Calamity in a more sudden and violent form visited the town on June 13, 1917 when a poorly sited TNT factory exploded claiming the lives of 43 locals and leaving hundreds homeless.

From here until Huddersfield we'll be running close to the Huddersfield Narrow Canal, a man-made waterway that traverses the Pennines with the help of 74 locks and Britain's longest canal tunnel. The HNC operated for about forty years without railway competition, but from day one (1811) struggled to compete against the Rochdale Canal, a longer but broader trade artery that reached Huddersfield by a less demanding, more northerly route. The lack of virtual narrow boats on the virtual HNC is a little disappointing but isn't unhistorical. As the multi-million pound restoration effort that restored navigability to this long-neglected waterway was still in its infancy in the early Eighties, strictly speaking the canal should be modelled full of reeds and shopping trolleys.

That blur was Stalybridge, the town in which Great War spirit lifter 'It's a Long Way to Tipperary' was written, and the Chartism-influenced Plug Plot Riots gathered momentum. Described by some as Britain's first General Strike, the country-wide industrial action that threatened to paralyse England in 1842, began with steam engine sabotage (boiler plug removing) by disgruntled miners in Staffordshire and mill workers in this valley.

If you look to your right as we round the next curve you'll see the colossal cooling towers of Hartshead power station. Today, the plant – well, what's left of it – generates chills and atmospheric urbex snaps rather than electricity.

Nestling below a high rock wall, picturesque Mossley Station once boasted a Victoria Cross winner amongst its staff. Private Ernest Sykes, a Northumberland Fusilier decorated for rescuing several wounded comrades “under conditions which appeared to be certain death” in April 1917, may on occasion have looked up from his labours to see the LNWR Claughton-Class steam locomotive named in his honour barrelling past.

You may not have noticed it but we've been climbing continuously since leaving Manchester. On the top of that disappointingly bald, crudely textured hill on the eastern side of the valley sits Saddleworth Moor, a place with associations as dark as they are infamous. In 2016 a less sordid mystery briefly upstaged the search for missing murder victim remains. For a while it appeared 'Neil Dovestone', an ID-less elderly man discovered dead on the Moor, might have travelled all the way from Pakistan just to end his life at this lonely spot because he had a connection with a 1949 aircraft accident that occurred nearby. When 'Neil's' true identity eventually emerged a year after his body was found, it turned out there was no link with the DC-3 crash... no neat symmetrical story. David Lytton's reasons for choosing this particular piece of the Pennines as a deathplace may never be known.

We just dashed past Diggle, one of several stations on this line culled by the Beeching Axe in the late 1960s. That means we'll soon be arriving at Standedge, the place where Victorian navigators stopped cutting, banking and viaducting and started boring. There are actually four, three mile-long tunnels under the Pennines at this point. The earliest, the canal tunnel (1811), was followed by two single track rail tunnels (1848 and 1871) that proved to be bottlenecks and were eventually supplemented with a twin track tunnel in 1894. Lined with approximately 25 million bricks the 1894 bore is the only one still used by trains, but in an emergency its neighbours could be pressed into service for evacuation.

While rail travellers only have to endure the Stygian gloom of Standedge Tunnel for a few minutes, narrow boat skippers sometimes spent as long as three hours under the rock, bracken, and spoil heaps of Pule Hill. To minimise construction costs, the canal tunnel was built without a towpath, which meant narrow boats had to be laboriously 'legged' through while their equine engines were led across the moor above.

Bafflingly the UE4-powered TSW is still awful at tunnel ambience. If you were sitting beside me in the cab of 45119 right now you'd see nothing but inky blackness broken intermittently by a bizarre strobe effect on the nose of the loco. Dimly illumined tunnel walls? Occasional drips of water streaking the windscreen? Not a chance.

Oh well, at least the tunnel's eastern portal with its distinctive stepped aqueduct over the line is lovingly reproduced.

On the Manchester side of the Pennines the textile industry was dominated by cotton. On the Huddersfield/Leeds side wool tended to be the focus. Marsden, the settlement flashing past at present, was dominated by Bank Bottom Mill, one of the largest and most striking wool cloth factories in Yorkshire. Dovetail's landscapers have attempted to represent impressive edifices like this, but their use of generic structures inevitably means urban vistas aren't as colourful or evocative as they might have been.

While you may never have visited Marsden before, there's a chance you've seen it on your TV screen. An isolated local shop for local people once stood on moorland south of the town.

The Colne Valley produced other things than cloth during its industrial heyday. We're currently close to the site of a factory that generated inestimable joy during the century or so it was in operation (the old Standard Fireworks factory on Crosland Hill) and two plants that were vital to Britain's war effort between 1939 and 1945. Gears produced at David Brown Ltd's premises over yonder ensured Bristol and Rolls-Royce aero engines turned flawlessly, and Churchill tanks steered crisply; tractors produced by the same company down the road at Meltham tilled British fields and helped bomb-up and manhandle RAF bombers.

This rather ugly rock cutting opens onto Huddersfield station, a competently simmed structure that arguably needs a few muffled tannoy announcements and the odd passing freight train to really come alive (Currently there's not a wagon to be seen anywhere on the line).

Known for its handsome neo-classical façade and, more recently, its pair of resident felines, the station can be viewed from St Georges Square in TSW but sightseers will probably return disappointed.

Entering Yorkshire's Heavy Woollen District, an area that gave the English language the word 'shoddy' and for years supplied the world's armies with hard-wearing fabric for uniforms and blankets, we serenade another impressive power station with Sulzer songs (Like Hartshead, Ravensthorpe hasn't survived) beetle through Mirfield (the birthplace of everyone's favourite Shakespearian actor/ starship captain) and pass a ludicrously empty fan of sidings. Dewsbury unfurls, Batley briefly distracts, and before we know it we are plunging into the line's second significant tunnel. Apart from a few outsized and unsimmed ventilator shafts lurking incongruously amongst homes and businesses there are few indications that two miles of iron road run under the town of Morley.

Our serpentine path into Leeds takes us through Holbeck, a district dominated by Victorian architecture at its most utilitarian but blessed with two period buildings that are fanciful to the point of implausibility. That eye-catching Italianate brick tower to the right isn't part of a church or university. A homage to Giotto's Campanile in Florence, it once ventilated part of Tower Works, a factory that made pins for carding and combing. A little further south sits - in real life at least - a flax mill masquerading as an ancient Egyptian temple. Said to be 'the largest room in the world' when built in the late 1830s, Temple Works featured a vast turfed and skylighted roof grazed by sheep. The elevated pasture helped maintain the humidity levels necessary for keeping linen thread supple.

Leeds. The next stop will be Leeds. Alight here for trains to Bradford, York, etc or simply to sit for a while undisturbed by topographical trivia. Obviously, I intend to travel on to Edinburgh using nothing but Wikipedia and my imagination, but I can totally understand why you might want to do your own thing at this point.

For anyone disappointed that this wasn't a proper Train Sim World®: Northern Trans-Pennine: Manchester - Leeds Route Add-On review, kick up a sufficiently pungent stink in the comments section and I may return next week with physics analysis and cold, hard judgements.

* * *