The RPG Scrollbars: The Many Faces Of Villainy

SHODAN at the Better Than OK Corral

Not only does a great hero need a great villain, villains are usually just so much more fun. Whether it's the tortured lost soul who can only find peace by destroying the universe or the cheery psychopath looking to see the world burn, it's no wonder that many of the greatest films of all time have been defined at least as much by the baddie as any individual scene. Darth Vader, the Terminator, Norman Bates, Dracula... villains get people excited. A great villain lives forever, death be damned.

It's particularly relevant because the RPGs with great villains offer some of the best and most iconic that the industry has to offer. SHODAN. The Guardian. Darth Traya. Kefka. The Transcendent One. Irenicus. Ironically, RPGs both have a huge advantage over other genres and a massive disadvantage - their length. Used properly, a villain can dip in and out of the action with an excellent rhythm, presenting not just an evil plan that has to be stopped, but building up a relationship with both the player and the main characters that makes it personal. That makes their final defeat satisfying.

Prince LaCroix of Bloodlines, for instance, is a fantastic character - an eminently punchable smooth talker who can't conceal the fact that his control over Los Angeles is shaky at best, who spends most of the game trying to kill you with impossible tasks since he didn't have the political clout to actually order your execution during the intro, and who the player character is ultimately (if somewhat awkwardly given Vampire: The Masquerade generation rules) able to overpower and put in his place by outright no-selling his Domination ability and telling him where to stick his authority.

The catch is that a villain who keeps showing up to win, destroying your recent achievements, quickly gets incredibly annoying, while one who just loses all the time rarely maintains much gravitas. Even beating them repeatedly gets annoying, as the makers of BioShock 2 - not an RPG, but stick with me - found with the character of the Big Sister. This was originally one entity, but having her always zipping off before the final blow just proved annoying, resulting in the developers turning her into a whole class of enemies instead. Also, when a villain does get a major success, it has to be incredibly well handled to make it feel dramatic rather than simply frustrating.

Compare, say, Baldur's Gate 2 and Knights of the Old Republic. Baldur's Gate 2 starts, more or less, with the villain kidnapping your childhood friend Imoen by proxy in order to make you come after her. He does this first with his magic, and then essentially setting the local magic cops on her in a way that you as the player have no chance whatsoever of fighting back against, even if you try. The game however quickly gives you another character who is basically Imoen 2.0, Imoen wasn't around long enough to have seen favouritism that would affect the others, the game gives her back before too long, and the whole thing comes across as the villain being canny rather than the designer of that section being a bastard.

Knights of the Old Republic meanwhile features a hilariously easy mid-game battle with the final boss, Darth Malak, in which he gets his ass completely kicked, before your partner/party member Bastilla goes "Don't worry, I've got this!", takes over, and is promptly kidnapped. This is having just spoiled your chance to save the galaxy in one easy battle, saving nobody, and not even having the stats that would make sense for a one-on-one battle, regardless of the fact that pride has repeatedly been shown to be her downfall. The idea is to put her into Malak's clutches while showing off his power. The result is closer to "Just keep the silly bint."

Most enemies though don't get anything like this kind of screentime. They tend to suffer from what TV Tropes refers to as Orcus On His Throne; specifically that they're big and tough and totally ready to conquer the world, only for some reason they seem to have been superglued to their chair. This can still work. The Lich King of World of Warcraft spends most of the Wrath of the Lich King expansion popping up psychically to taunt the heroes, and putting them into dark situations, with the plot also resting on the (retcon) that the Lich King himself is in the middle of something of a civil war between his human side, Arthas, and demon side, Ner'zhul, that's preventing him from unleashing the full world-crushing power of his zombie army. (There's also some bullshit about planning to turn players into his new generals, though as has been pointed out many times, when it takes up to 25 of them at the appropriate level to kill just one of his previous guys in a fair fight, he should probably stick with what he's got. Especially when they include dragons. Dragons are awesome.)

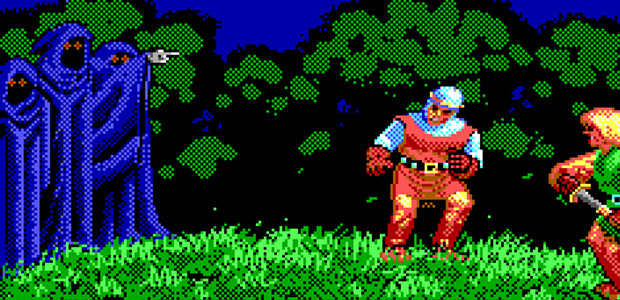

Even in this case though, the Lich King isn't afraid to get involved - to get his hands dirty. In many a classic RPG, you don't even know who or what the villain is for much of the action, or it's just some spiky-shouldered person who pops up in the intro movie and a couple of times to snarl. The Guardian of Ultima VII certainly wasn't the first to get more involved, with the Shadowlords of Ultima V being a wonderfully corruptive and intimidating force, but he was one of the earliest cases of a villain being pushed right to the foreground and harnessing new technology to create something memorable. Within the world of Britannia, his only real power is his ability to speak. This was mirrored in our world by him being one of the first major talking RPG characters - not just going 'ouch' or similar, but delivering long speeches about his evil plan in the intro. You never actually meet him in the game, with the ending being to blow up a magic Black Gate before he can come through and become godlike, but he's a constant presence throughout. He talks to you in your sleep. He laughs when you come across his evil plans. He screams at you to turn around when you approach his evil.

Played now, admittedly, things aren't quite as effective. Those speeches are incredibly camp, the guy looks like a Muppet and villains who literally go 'mwah-ha-ha-ha' are so old fashioned, he might as well be tying Penelope the schoolma'am to train tracks and twirling his moustache. Even so, he largely set the pattern for many a successful villain to come - be passionate, be ambitious, but above all else, be there. Say what you will about Ultima VII's campiness, the player never forgets who the villain is.

And it's at least a little more subtle than, say, Clouds of Xeen.

The Guardian, of course, led more or less directly to SHODAN of System Shock fame, who is a very similar character in many ways - and certainly execution. The big difference is that while the Guardian talked a big game, he didn't have many real tricks up his sleeve. SHODAN meanwhile controls an entire space station, with the whole game playing out as a glorified game of cat-and-mouse where the cat is happy to lock the mouse in the nuclear reactor or devote big chunks of a floor to creating a death machine gauntlet out of a former corridor.

Again though, it's not just raw power that makes SHODAN interesting. As with Ultima VII, the raw dialogue is... somewhat campy. System Shock 2 would greatly improve the writing quality. Even so, there's subtlety to it, like the fact that her dialogue to her robots (who as far as we can tell really aren't smart enough to care) is all self-glorification and fancy speeches as befits her self-proclaimed goddess status, while most of her comments to the player are pointed and irritable, as if annoyed at having to waste time. Likewise, because she's the computer system and therefore hooked directly into every single part of the station, pretty much every player act feels like chip-chip-chipping away at her specifically. Knock out a camera and you blind her. Hack a door and you crawl through her fingers. SHODAN makes the entire environment feel like a living creature, even when in raw script terms it's relatively simple.

Part of the issue with many villains is that their goals simply aren't sympathetic. It's not hard to write one who wants to conquer the world for funsies, or who just happens to have an invading army or believes that it's their job to save the world by destroying most of it. Very few RPGs, however, have managed to create a set-up where the villain claims they were only doing what was right, and for the response to be "And I get that." As an example, Fable 3 fails miserably here. The concept is that your brother, the king, is secretly preparing Albion for an invasion that nobody else knows about, with his deep-seated douchery actually just about saving money and preparing the land. Unfortunately, the threat turns out to be hilariously unimpressive, with the player easily able to personally afford the necessary army out of the equivalent of petty-cash.

The most successful case I can think of is Loghain, the villain of Dragon Age: Origins. He looks like the villain and he spends most of the game up to his gauntlets in dodgy dealings when he should be helping you and your fellow Grey Wardens handle the Blight. Indeed, it's easy to play through the game and see him as just another would-be conquerer, who abandoned his king to steal his throne.

Pay more attention though, especially if you follow the path where he joins the party and gets to have his say more directly, and a much more rounded figure emerges - one who has excellent reason to doubt the upcoming disaster and suspect the heroes as being merely part of a scheme from another empire. He's also shown to be ruthless, yes, but with a strong sense of honour, with abandoning the King not a particularly dreadful idea given his dreadful tactics. Once he discovers that only a blood sacrifice will be enough to save his kingdom, he's also the first to volunteer, having realised his mistakes and started looking for a way to atone. At every point though, his actions - even if ill-informed or morally questionable - are firmly focused on what's best for his country. That doesn't necessarily make him a hero. After all, many bad things have been done for patriotism. However, nor does it make him a moustache-twirler.

Caesar from Fallout: New Vegas operates in a similar way, but with an important twist. He's the head of the 'baddie' faction, Caesar's Legion, and most of your encounters with them are hostile or deeply awful, despite some attempts to justify the cruelties as paying evil unto evil and making a point in order to prevent other, worse atrocities. You meet him, and what quickly becomes clear is that far from a crazed madman, he's a scholar, he's thought all of this out extremely carefully, and he has a very structured, careful plan. The twist is that having made a man out of the monster, New Vegas has no compunction about showing that under that is a hypocrite, a poor tactician, and a whole other layer of monsterdom that's arguably worse than the show he puts on. It's something of a flaw in the game in that there is literally no good reason to support his faction except for doing an Evil Run, but a great character study that subverts expectations by revealing that there isn't actually a clever writing twist on the way.

(Naturally, this kind of thing is fairly common in Fallout, not least with the ability to talk the Master of the mutants in Fallout 1 out of his plan on the grounds that it won't work, leading to him blowing up his own base and saving you the hassle of it.)

One of the classic rules for writing villains is that they should usually be the heroes of their own tales. Personally, I've never liked things so cut and dry. There are fantastic villains who are well aware of their status, carrying out their acts because they feel that they must. Kreia/Darth Traya of Knights of the Old Republic 2 is under no illusions about who and what she is. Her Sith name even marks her as a professional betrayer. Likewise, The Transcendent One of Planescape Torment shows no interest in anything except silent immortality, and its meddling with The Nameless One is entirely a matter of frustration for them both. Then of course you get cases like Kefka of Final Fantasy VI, who has all the depth of a paddling pool but caught peoples' attention for being crazier than your average villain, and Sephiroth of Final Fantasy VII, who... well, I won't say there's nothing to him, but let's face it, the hair, the sword, and the orchestra screaming his name really didn't hurt his credibility.

Of course, if Sephiroth is remembered for anything except his style... and I'm fairly sure he is... it's That Moment, killing Aerith mid-way through Final Fantasy VII. That opens up a whole can of worms for the genre. Specifically, when is it okay for villains to have that level of success? It's one thing to burn the player's hometown that they don't know or care about, or whole locations like Highpool and Ag Centre in Wasteland 2 to prove that they're serious. What matters to the character though has to be made to matter to the player, and simply saying 'you feel really sad about this' doesn't cut it.

Few games though are willing to let them outright get a kill that sticks and has a mechanical impact. Mass Effect features a section where the player must choose between two party members and others later on where diplomacy fails or is very difficult. Not many though have the guts to 'pull an Aerith', despite the potential power of it, and those that do almost inevitably make the actual moment that happens into the player's call, with the promise that something else could have been done. Dogs excepted, of course. From Dogmeat to the pup in Fable 2, a happy dog bounding at your feet has a worse chance than most NPCs of making it to the credits.

The reasons are many, starting with the fact that characters die so often in RPGs that making one of them stick is a hard pill to swallow, even in a world without easy access to resurrection, and that a company trying to create memorable IP would rather keep them around rather than losing someone popular. Where would Mass Effect be if instead of a choice between Ashley and Kaidan, the player had been forced to choose between Tali and Garrus? Pity the Tumblr community...

Mostly though, it comes down to the fact that it's about 50/50 odds that the player's annoyance will be aimed at the company/designer of the sequence rather than the villain who supposedly did it. That's quite a hefty risk to take, especially if it's a case like the Bastila example of KOTOR where there was clearly no need for it. Things get worse if going back, it really was a forced situation, like watching a magician's volunteer pick the three of clubs for the second time. (The Walking Dead: 300 Days features a section in a cornfield where a character's identity changes based on your decision to ensure that whatever you do, you mess up the scene - either being shot by a villain and dying, or whacking a friendly character. That's not just a problem for that scene. You get caught doing that, and the player won't trust the game again.)

As with so much, games have a unique advantage when it comes to villains in that they can make things personal. As in the above examples, there's almost endless ways to play them and subvert the expected rules. Undertale is a fun recent example, where everyone talks about the presumed final boss, King Asgore, like he's a giant lump of marshmallow rather than your actual nemesis, with the big twist being... he basically is. He fights purely because he knows a fight is inevitable, doing everything he can to put it off not because he's afraid of losing, but because he doesn't want to win. Dark Souls 2 sets up King Vendrick as its big bad, only to reveal him as a stumbling zombie no longer able to prevent you just walking up and taking his ring. I'm sure you can think of many other examples of cool villains, and as ever, comments thread below.

If there's one big thing that basically all of these great villains has in common that other games can learn from though, it's presence. It doesn't matter how much power someone supposedly has, or how many hit-points they mechanically have in their final encounter, if they're just another obstacle. The nemesis is at least as important as the hero in most games and requires suitable screen-time, character depth, and the time to make a proper impression. Facing off with them can be many things. Cathartic. Satisfying. Bittersweet. But what it should never be is simply business as usual.

A good villain deserves better than that. And a great game deserves a great villain.