Why Creeper World's decade-long evolution keeps getting harder

Feature creep

“The whole history of the Creeper World series is serendipitous and unintentional,” says its creator, Virgil Wall, in his Texan lilt. “You know how it goes with these things, one thing led to another.”

Creeper World is a singular take on the realtime strategy that Wall has spent the past decade making. Former man of the cloth Kieron Gillen once described the original as “the most apocalyptic game I’ve played in ages”, an RTS about managing constant attritional threat. But it’s also a game about simplicity. As Wall puts it, “its original purpose was to throw strategy gaming into a crucible and turn up the Bunsen burner as hot as it could get and boil away anything except the essence.”

But that’s led to 10 years of grappling with a constant problem: how do you design follow-ups to a game that was already boiled down to its essentials?

Creeper World’s origin is in, as Wall tells me, “a piece of a failed game”. Back in the 2000s, he was a vice president of software development at a publicly traded company. He was responsible for engineering networking, banking and security software, he had a whiteboard-festooned office, and he didn’t really get to program any more. And then in 2007 he noticed the growth of the Flash gaming scene.

”It reminded me of gaming in the 80s and 90s, the intense engineering constraints where you have to tell a story and make an interesting game in a tight box. I was interested in that and I had to keep my skills sharp because I wasn’t programming anything by day, so at night I wanted to explore it.”

His first game was Whiteboard War CHOP RAIDER, an homage to Will Wright’s Raid on Bungeling Bay, and he was surprised to see it make $15,000 in ad revenue in a year. “I’m like, what? Are you kidding? Really? For three months of goofing around in Flash at night?”

So he started to make a new game, a space strategy which was similarly tightly constrained. After six months it wasn’t working out, but he liked one part of it, a fog of war mechanic whereby the player would shoot probes out which, when they hit the fog, deployed to reveal the surrounding area.

“What if the fog of war came back and you have to keep shooting it?” he wondered. ”That turned into this thing I’ve been working on for the last 10 years.”

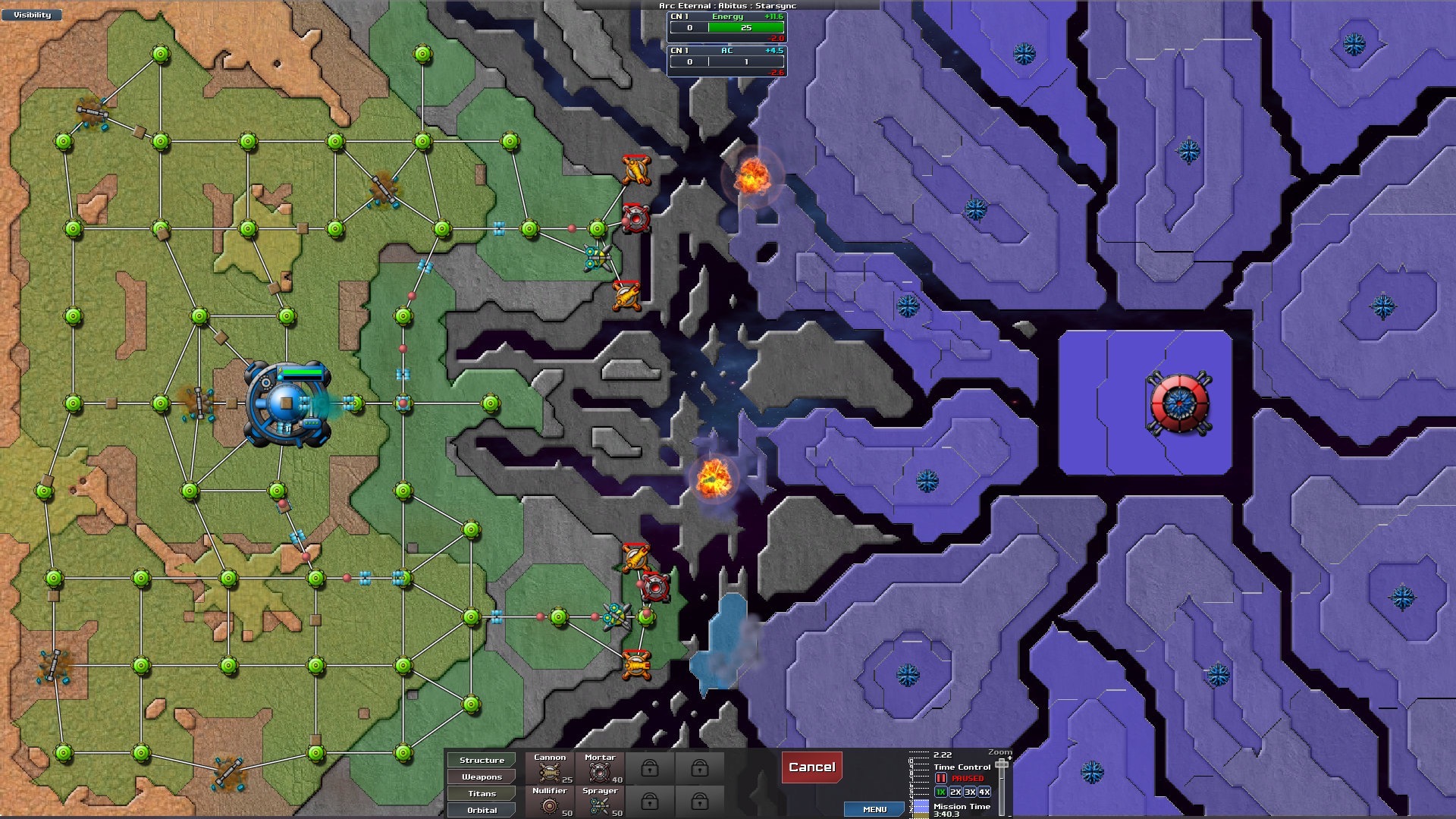

Creeper is a viscous tide of gloop that’s generated at points across each level’s terrain and its spread is simulated using cellular automaton. Your basic job is to build a network of resource collectors that feed energy to build and supply weaponry that will reclaim territory and fight the creeper back to its source, inch-by-inch.

Wall immediately liked the idea because it dispensed with various bits of RTS design he was beginning to see as cruft. You weren’t fighting an enemy which was fundamentally the same as you. It didn’t involve pathfinding (“pathfinding is usually an irritation for the developer and the player and it doesn’t have anything to do with the higher level strategic elements of getting units to the front line”), and it’d run in a browser so he could host a demo to inspire sales.

“And I wanted it to be a tight game. I saw strategy games getting bigger and bigger, the size of the maps, the number of units, five re-skinned copies of the same unit. I wanted to get rid of the stuff that plagued strategy games and make it something you could play in 10, 15 minutes and not just be tower defence.”

Wall soon discovered that such a tight space for rules brought problems.

“It became immediately obvious it’d be difficult to get enough variety in the missions,” he says. “This remains a problem in every game.”

He knew he could stagger the rate at which the missions reveal units, and add story elements and surprise one-time events. “But how does that scale to 5000 missions?” After all, another aim he had for the first Creeper World, and every subsequent game, is that it’d ship with a map editor so players would constantly feed new missions to the community.

He needn’t have worried so much. While Creeper World’s core design is tightly focused, lots of strategy naturally emerges from its concepts of line of sight, high ground and resource management, not to mention the macro of managing full frontal attack and defence, and the micro of managing advances and retreats. The first Creeper World’s map editor might have been simple, but players went to town, adding custom graphics and new modes of play, squeezing more out of the game’s 70x48 grid than he’d ever imagined. Now there are over 6,500 of them.

But there was a second problem with creating such a constrained game. How could he make a sequel that expanded on the first without bloating out the simplicity he was proud of achieving?

In Creeper World 2, Wall went in a new direction, presenting the action from the side rather than from above. It featured strategies that emerged from the first, and the new viewpoint presented new ones besides. Wall realised that creeper could generate and be contained in caves, becoming denser over time so that when you dig into a pocket it explodes with force relative to how long it’s been building up. (Deal with them by staging managed retreats, or move quick.)

For the third game, Wall returned to a top-down view but exchanged Adobe Air for Unity. Though it still worked in browsers, the additional power allowed larger maps and a much more complex simulation for the creeper. But that wasn’t really the source of Creeper World 3’s depth.

“It was sort of an accident,” says Wall. Creeper World 3’s scripting language lets map designers create new enemies, mission events and other custom elements and has become a huge part of the game. But he hadn’t planned to make it. He simply wanted a way of scheduling attacks from a spore tower, which launches airborne creeper at your base. But as he added an interpreter which could take in variables based on what’s happening on the map, he realised he’d made something more significant.

“Three months later it was a full-bore scripting language! It was thrilling to me because it was good for the game and good for the players and when I made the story missions I could get a lot of variety across them.”

Players have created Play As Creeper maps, creeper monsters that appear from the gloop, and mechanics that can teleport creeper around the map. “The community became the additional mechanic, which was not what I planned.”

The community was also an inspiration for Creeper World 3’s campaign. Using user-ratings and play counts, Wall studied the popular user-maps from the first two games to see why they were good. ”I also looked at the other end of the spectrum, the ones people said were awful. Then there were these weird maps in the middle that were low rated but highly played. People keep playing them but they don’t like them! Then there’s another category, the maps that people didn’t really play but were rated highly.”

But it didn’t stop Wall from making a mistake. He knew that Creeper World supports lots of play styles, including those who like to take their time, but he also wanted to present a big challenge at the end. The result was Farbor.

“So many people hate that mission, they’ll play the game for 200 hours and leave a negative Steam review because of it.” And that’s despite Wall posting a save that skips the mission and walkthroughs on YouTube.

The problem is that Farbor features a countdown timer: if you don’t complete it in 20 minutes, the mission seems to end. “In playtesting I discovered people didn’t like the hard ending, so I made it a soft one - the story changes but life goes on and you have another 20 minutes.” But Wall hadn’t accounted for players who rage quit before they learn they’re getting more time, and it’s become notorious. “I won’t make those mistakes again,” Wall says.

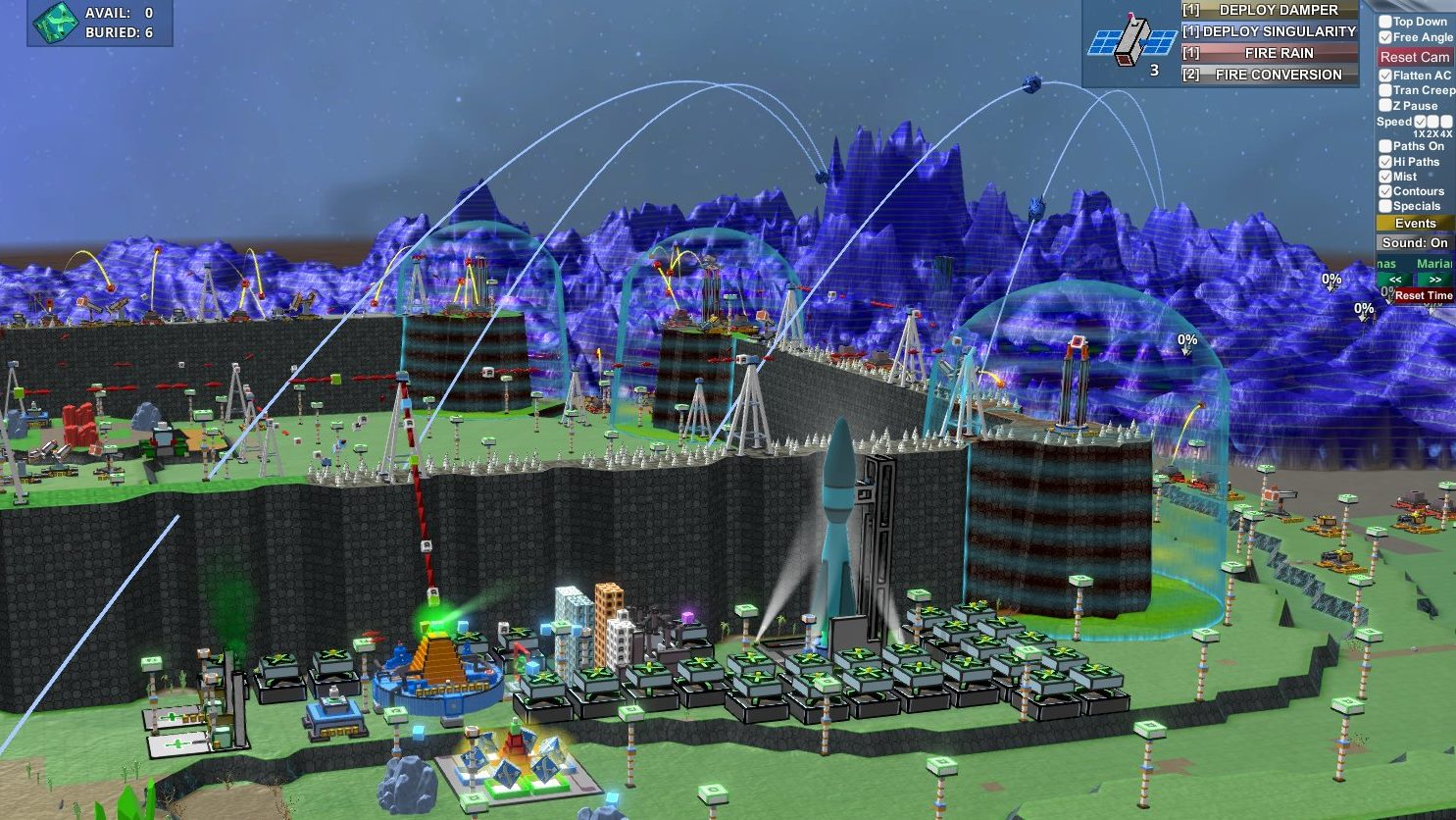

That’s fortunate, because now he’s tackling the challenge of designing Creeper World 4. The innovation here is that it’s 3D, so you can see great towers of creeper coming at you, giving an even greater sense of apocalypse.

But despite the spectacle, Wall says it’s presenting all the same problems, “but worse”. On top of maintaining all the series’ defining tight constraints, he’s anxious about leaving anything out that was in Creeper World 3. “There are far too many cautionary tales; what’s left out defines the game.” And he’s simultaneously nervous of making it play too similarly, and thus being accused of making a 3D port of a 2D game.

His process is to build new ideas and present them in YouTube videos so he can gauge reactions in the comments. One such test was on an expansion of the game’s economy with new resources needed to capture specific points on the map. Opinions were divided. He scaled back on the concept of managing factories to produce certain resources and will present the result to see if he’s found the right balance.

It’s a lot of work, but he clearly feels it’s worth it. “I added this frozen time thing and 80% of the feedback was negative,” he says. “Really? I thought it was awesome. I continued to play with it and realised they were right, it was a pleasure to develop and watch work but it wasn’t a pleasure to play.”

As much as Wall pretty much makes Creeper World entirely on his own, it’s been the games’ players who have done the most to solve the problem of extending a game that flows from a simple core.