Why Valheim wants to stop you using portals

Portals are historically inaccurate anyway

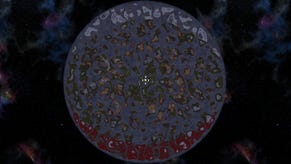

Valheim is a survival game in which you grub around in forests for wood and leather scraps and steadily build your base into a towering castle. It’s also a game in which you’re a Viking who goes on epic voyages to distant islands for fortune and enough glory to ascend to Valhalla. Why not both, right? Well, one reason why not is that these two ideals sometimes rub up against each other the wrong way.

Developer Iron Gate Studio found a particular pressure point when they came to design its portals, which instantly teleport players across the game world. “We redesigned them several times because we didn’t want people to use them too much,” co-founder Henrik Törnqvist tells me. But why would you put something in a game that you don’t want players to use?

Something important to know about Valheim is that Törnqvist and his co-lead, Richard Svensson, are really into the Elder Scrolls series, especially the stupefyingly vast Daggerfall, which contains over 15,000 settlements and dungeons. They love the sense of exploring big, open spaces, so much so that early in Valheim’s development, the world was much bigger than it is today.

But they also know that there’s a point at which all that open space stops adding anything to the experience. “You’ve got to have something to fill it, or to put it another way, there’s got to be an end point to every journey,” says Törnqvist.

So they squeezed Valheim down to better balance its sense of wilderness with its places of interest, at least in terms of how many interesting places its tiny five-person team could reasonably produce. The result is a world that encourages you to explore it, one in which you can feel enveloped by wilderness and also trust that you’ll likely come across something remarkable that makes every journey worthwhile.

As an aside, Törnqvist isn’t sure they’ve quite nailed those points of interest yet. Valheim, after all, is still in Early Access. “I talked about having really unique locations during development,” he says. “They’re something that I personally think the game lacks a bit, like coming across something really spectacular, a giant castle complex or something, and perhaps there’s only one of this castle in the world. We would definitely like to add unique stuff like that.”

Anyway, Törnqvist and Svensson wanted Valheim to be very much about being a Viking, with players building boats and sailing the seas between the islands that make up its world. All of this means that at a deep level, Valheim is a game of journeys, and it wants you to feel like a stranger in unknown lands and to need to make footholds in them.

Valheim is a game of journeys, and it wants you to feel like a stranger in unknown lands.

“We want players to build many bases as they progress, because many building pieces and such things are unlocked as you go, so you don’t have access to everything from the beginning,” says Törnqvist. “We wanted people to experience building multiple times but with different ingredients, so to speak.”

But while it’s exciting to think about the idea of building a base up and then making the commitment to leave it behind for distant shores, in practice it can feel a little bad to give up on all that work and creativity. So it was obvious from early on that Valheim would have portals to instantly teleport players across the world.

But problems soon became evident. In playtests, Valheim became a portal-building game in which players would set sail, build a portal back to base, and never take to the seas again until they had to reach the next island. “We want physical exploration to be a big part of the game,” says Törnqvist, but portals were replacing the need for most journeys.

What’s more, portals also meant players could sidestep a lot of the challenges set on later islands and biomes. They’d portal all the resources they gathered in new biomes back all to their main base so they never had to set down roots in them. “I mean, it’s a bit boring. We want players to play in all the biomes,” says Törnqvist.

To Svensson, at least, it was clear that portals had to be limited in scope. But how? One idea was to have them cost something. “But that really doesn’t solve anything,” says Törnqvist. “It just becomes more busywork to gather the stuff that you need to teleport, and that one time you need to teleport something and you don’t have the resources for it, it becomes an irritating moment, you know?”

It was clear that the issue with portals was the way they transported resources, so another early idea was to have different tiers of portals, so low-grade ones couldn’t transport any minerals, better ones could transport copper and tin, and the best could also transport iron.

Portals reveal the tension between these two sides of Valheim’s gold coin. Building games often rely on convenience, while grand adventures are often at odds with it.

Having three tiers added too much complexity to the game, but the basic idea proved good enough to ship in the current version of the game. You can only build one type of portal, and you can’t take through it any kind of metal or ore. This means that you have to physically transport the resources which form the backbone of Valheim’s crafting system through the world, while common resources like wood and stone can go through, along with special items like gems and trophies. The inventory is very clear about what can’t be teleported, marking ore and metals with a little icon and noting it in their tooltips.

Thinking about Iron Gate’s solution made me realise that Minecraft must have faced a similar issue with its portals, and it used a very different solution that I’d never before appreciated (disclaimer: I work for Minecraft’s maker, Mojang). I’ve never considered using portals to shortcut the dangers and challenges of the Nether, and the reason is in their design: if I was to place a portal near a hazardous but rewarding location in the Nether like a bastion, it will take me miles from my base in the Overworld. That’s because portals between the Nether and Overworld are linked in space, but at different scales: a distance of one block in the Nether equates to eight in the Overworld.

This option wasn’t available to Iron Gate: Valheim’s world is contiguous while Minecraft’s portals take you to alternative dimensions. But it shows that portals are difficult for a lot of open-world survival games.

Törnqvist, however, isn’t behind the ores ’n’ metals solution at all. “I personally love the portals!” he tells me. “I think they would probably be better if we let players transport everything through them.”

Unfortunately, Svensson couldn’t join us when we spoke because he was unwell, but it’s clear that portals inspired some strong discussions over Valheim’s development, and Svensson’s take took precedent, in part because he’s the game’s originator. What’s interesting, however, is that the difference between his and Törnqvist’s differing takes on portals reflects what they’re personally looking for in open-world survival games.

“I’m the guy who likes to build a house and just sit there, basically,” says Törnqvist. “Collect some stuff, build a new addition, a blacksmith. Richard is more about the adventure, exploring the world.” It’s fitting that the game they made together reflects both of these stances: Valheim is a game about being a Viking and being brave and proving yourself, and it’s also about digging in and making a comfortable life for yourself.

Portals reveal the tension between these two sides of Valheim’s gold coin. Building games often rely on convenience, while grand adventures are often at odds with it. Whether Valheim currently strikes a balance between creation and adventure, Iron Gate aren’t quite sure yet. They haven’t had many complaints about portals, but then again, it’s early days for the game and Törnqvist thinks it’s quite likely that the majority of players haven’t yet reached the part of the game in which portals become important.

“I think - and this is just me guessing - that many players just like to travel around the starting area,” he says. “That’s what I like to do, to be honest.”