Wot I Think: Kentucky Route Zero - Act III

Nothing to be done

Here at RPS, we're quite fond of Cardboard Computer's magical realist adventure. Kentucky Route Zero took the final spot in our 2013 Advent Calendar and while the wait for the third act has been longer than I would have liked, it's good to have Conway and his companions back in my life. The new chapter of gaming's strangest trip since Sam and Max hit the road contains a musical performance worthy of Lynch, a whiskey-soaked underworld and enough melancholic mystery to fuel a new generation of the blues. Here's wot I think.

The punk with the metal legs is quoting Samuel Beckett as she leads our troubled collective into a dive bar by the name of The Lower Depths. She’s playing a gig with a guy she refers to as her ‘cricket’, and she’s running as late as a white rabbit or the corpse of a slacker. She’s already mentioned a couple of guys she knows called Didi and Gogo, and as we gather around the beerlight she throws out a snippet of Waiting For Godot. “We are not saints but we have kept our appointment.”

How many can boast as much, goes the rest of the line as Beckett wrote it.

Billions, is the deadpan response.

Conway doesn’t know the punchline though, doesn’t even recognise the comitragic joke, so he simply acknowledges the beauty of the line and asks where it came from.

“Who said it?”

“A poet,” says the punk. Is she talking about Beckett or is she talking about Vladimir, the creation who spoke the line? He’s sometimes called Didi, a man she has already claimed a passing acquaintance with. The cast of Kentucky Route Zero are infiltrated and haunted by characters from our world and from many others. This new Act, along with interlude The Entertainment, contains the most explicit blurring of the lines between creators and the things they create. In Kentucky, Samuel Beckett may never have existed at all but his characters did and so do lonely limbo trees at the side of the road.

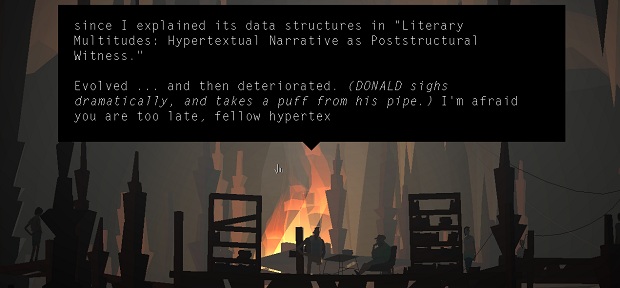

As the adventure continues, certain techniques are becoming motifs and there’s a sense of comfort and cohesion when they arise again. In the story’s most perfectly executed scene to date, interiors swim away in familiar fashion during a dreamlike player-directed musical performance, leaving audience and band stranded in a glowing nowhere. We watch them as they watch a transcendent display, and later there is a game within the game to sit alongside the play within a play.

The impossible dismantling of scenery, which has been occurring since Act I, carries the suggestion that the characters exist on a stage set. The hotspots, waiting for a cursor and a click, are the active props. Along with these visual clues the themes of memory loss, disassociation and death that run through the writing are reminders that theatres have always been home to ghosts. Whether it contains the explicit phantom of a Banquo or Daddy Hamlet or simply the echoes of past performances, the stage is a haunted place.

On one level, Kentucky Route Zero does appear to be a ghost story, taking the form of wordy tours of various afterlives. Those afterlives aren’t always spiritual, just as the debts and burdens of the characters aren’t quite loads of sin to burn away in a waiting room before the pearly gates. Conway, Shannon and their growing gang of followers cross between the Lethean underworld of the Zero and the quiet rural desolation of overground Kentucky but while the player can occasionally choose to recollect and repent, there are other functions to fulfil.

It would be a mistake to explore Kentucky Route Zero’s narrative through the prism of any one character. The controls switch liberally from one to another and the player is in the role of the prompter at the side of the stage rather than pricking at the conscience of the king Conway. We’re not directors or writers, the game tells us at every step, we’re more like an audience being taken along for a ride. That’s not to say the interactive elements don’t matter but they’re more about the specifics of our engagement with the characters rather than any direct control over them.

I feel like I’m shaping Conway, Shannon and the rest, exaggerating the former’s boozehound past and the latter’s anxious attempt to retain a clear head while the past and future grow darker. A couple of scenes are slightly overlong, intentionally meandering around an obvious truth and sticking to conversational backroads, but that’s to be expected. The game is about the search for not only a destination but a route – it was bound to meander and mostly it does so with a determination at odds with the verb.

There are brilliant lines to discover in the most unexpected corners and the personal stories of each character are becoming clearer. Player choice is involved in the specifics of those histories and my vision of Conway as a tragic figure is becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Poor guy can’t catch a break when I’m selecting his dialogue and the direction of his occasional musing.

The strong form continues and there are enough meaningful hooks and connections here to reassure those who feared the writing might tend toward the nonsensical. Kentucky Route Zero’s world is infused with dust and drink, obscured as well as obscure, and while this act contains quiet revelations, it also muddies the firewater more than the previous two. There are machines in the ghosts now and down in the distillery, the spirits who tend to the spirits respond to a portable degausser with a flicker of life.

It’s possible to look at the entire game as an elaborate puzzle, a play on words and images that is tying all of its allusions into a knot of meaning, but I suspect that would be to miss the joke, just as Conway does when he fails to pick up on the Beckett reference mentioned earlier. Maybe it’s enough to enjoy the beauty of the fabric without worrying at each individual thread and picking at every stitch.

The game doesn’t encourage too close a reading, using its bag of learning to create atmosphere rather than an encyclopaedia of references. You don’t have to know Beckett’s work or the details of the Raines Law. Conway certainly doesn’t and it doesn’t matter because in his world the writer may not have existed even if his characters still do in some form.

As the Act ends, there’s a visual gag that risks undermining the more disturbing moments that precede it but everything just about manages to hang together, fragile as a hangover on a Monday morning. Earlier, when the static of the radio crackles and tunes into warped memories, the game drifts as close to dread as it has so far. I suspect there’s a horror game in Cardboard Computer’s future but Kentucky Route Zero isn’t it. The world might be weird but it tends toward absurdity rather than atrocities. I wouldn’t be surprised, or disappointed, if the final Act ended with a pratfall or a tragedy endlessly diverted by the power of a music hall routine.

After all, it was good enough for Godot.

Kentucky Route Zero is available now.