Wot I Think: The Bridge Review

Arch suspension

Obeying the new law that all puzzle games must rotate is The Bridge - a black and white, Escher-inspired set of reality bending puzzles from The Quantum Astrophysicists Guild. The last time we heard from it was a demo released in late 2011, but now it's here, on Steam, GamersGate and the Humble Store. But should you spend your £12? Here's wot I think.

If you've never stood with your forehead bent down touching the top of a broom, then span around it five or six times, then go do it now...

And yet people still spend money on expensive drugs. The Bridge is the gaming equivalent of the after-effects of such a spin, and then being asked to solve puzzles at the same time.

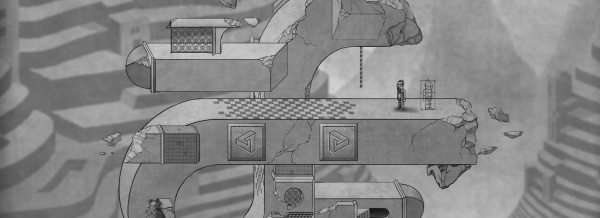

Using an Escher motif, levels ask you to do the simplest thing - open a door with a key. The issue is negotiating the rotating levels of interweaving impossible shapes and deadly stone balls. And inverted realities. And varying gravities... You move a middle-aged professor-looking chap - perhaps Escher himself - around small, constricted levels, that allow you to increasingly meddle with reality.

The game is ideally played with a controller, the world rotated with the triggers, movement on the analogue stick - that's just the best fit. And it's slow. On purpose. There's no running, no whizzing about - it's a paced game, a steady, increasingly complex set of challenges, to be negotiated at a sedate pace. Which is actually a bit of a problem at the start.

It's very easy for a long time. Levels are broken up into groups of five, with twenty-five in total for the first run through. The first ten of those are a breeze, and the lackadaisical pacing and oh-so-slow changes of scene get pretty frustrating. Get past these, and to the gradually more complicated tasks, and the speed matches the game far better.

Once things are nice and tricky, the game really finds its own. The single-screen scale (albeit varyingly zoomed out to allow slightly more elaborate sets) means there's a real tightness to the design. The smarts start shining through, as you realise that the limited set of options means you surely must be able to do it, surely! It starts requiring you to think more carefully, plot ahead, rotate things a certain way to manoeuvre other objects into the right place before you phase from the grey side to the white side, then step into the curtain that allows you to re-point the direction of one of the level's gravitational pulls. And it does all this without becoming cluttered, either on screen or in your own head.

However, it's a shame it doesn't sit still for long enough on any one idea. There are far more interesting places it could go with each level's motif, but they're abandoned too quickly, five levels before changing room, and a new set of rules come in. The last couple of levels provide a fun medley of all the various elements you've learned throughout, but it's still hard not to be left wanting more. Wanting to see a technique pushed further, to demand more out of you.

Then it rather does. I'm torn on whether explaining that a puzzle game continues after its apparent ending is a spoiler or not, but then again, trying to convince you to buy a 25 level puzzle game doesn't seem a great plan either. Finish it and you can enter a reversed world, where you go into a similar version of the same puzzles as the first time, but with the difficulty significantly ramped up. I'm just stumped on one at the moment, and hooray! Because while there were a couple of points where I wished there were walkthroughs already (I was playing before its release on Friday), I eventually spotted what I'd missed and was back on easy-ish street.

Its use of Escher-like designs permeates all, from the pencil-sketch style to the literally pencil sketched character, drawn in every level, to the levels themselves, constructed of impossible shapes. The one place it doesn't really reach far enough, oddly, is in moving around the levels. With the motif, I was really hoping for challenges which required me to take advantage of an impossible route, but more often than not you're walking inside or outside of routine patterns. Not always, and perhaps it's unfair to the game to be disappointed that when you do it's so nonchalant about it. Perhaps I just wanted something more gimmicky, because I'm a horrible, horrible sort.

Perhaps the most surprising effect of the game is the one experienced when I stopped playing. Things continued to rotate for me for a good couple of hours after, which made reading a monitor quite the thing. It's an extraordinary sensation, as my brain desperately tries to tell me that the sensible thing to do is to rotate the words I'm reading. Rotate the words? Brain, what? What are you doing?

It's all well worth a play. With the obscure quotes and meandering presentation, it does feel a little aloof, but what really counts are the puzzles, and they're in the main a real treat. It always looks utterly splendid, and it presents obscure concepts with consummate ease.