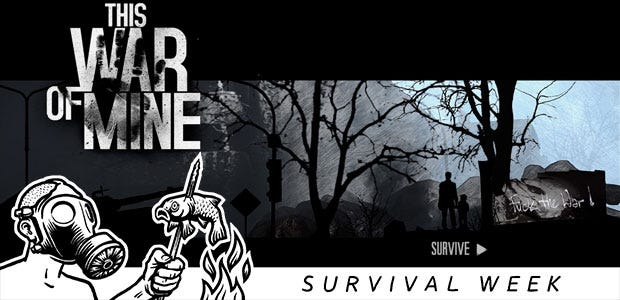

Interview: Warzone Survival In This War Of Mine

A war game with a civilian focus

"An experience of war seen from an entirely new angle". That's how 11 Bit Studios are pitching This War Of Mine. The new angle they're referring to is the fact that, instead of being an action-packed military shooter, their warzone is a city under siege and requires you to keep a band of civilians alive. Its desire not to glorify war reminds me of Ubisoft's recent Valiant Hearts but in terms of how the game works mechanically it's closer to Zafehouse Diaries – a zombie survival game with a diary storytelling element. I spoke to the game's senior writer to learn more.

Pop culture's zombies tend to be metaphors for various threats – everything from communism to prescription medication – but This War Of Mine prefers a literal approach. It keeps the crafting, scavenging and base-building common across the genre, and then switches the metaphorical zombie threat for literal effects of war. It's a game not designed to be enjoyable but engaging. I met up with senior writer Pawel Miechowski to talk about the challenges in creating a game like that. The formatting might seem a little odd but we were playing the game as we talked, hunched over Miechowski's chunky laptop at one of the Wellcome Collection's cafe tables.

RPS: Can you tell me what inspired the game?

Pawel Miechowski: It was an article by an anonymous author. It's called One Year In Hell and the man was describing his experiences [in the Bosnian war] – I think he's talking about Mostar. The river in the city quickly became contaminated because of the bodies. Obviously civilisation was down and there was no tap water or power. They needed water so they made a rainwater collector out of a barrel. When the winter struck they chopped down every wooden thing they had just to provide some warmth.

With these examples we started to think about this as a great topic for a game. But of course the game has its language – mechanics which need to be put in the game. We've stayed connected to reality as much as possible yet we were of course making a game which still needs to be engaging. For this reason there is no tutorial because when war breaks out no-one would tell you what to do, there would be no tutorial.

What people are struggling with the most is the emotional challenge. There's an article on Amnesty International which talks with a young lady who is wounded on the first day of the siege of Sarajevo. She was delivered to hospital. The hospitals were running all the time during the siege but very quickly they ran out of necessities like bandages and antibiotics. She was put on a bed next to an older lady and that night both were in bad shape. A doctor had to decide which of them should be saved – the doctor decided to save the younger lady because she had her whole life ahead of her. The same night the old lady died.

[Miechowski goes on to describe how characters in the game work – you begin with three but can lose or gain members of your core group over the course of the game]

Pawel Miechowski: All of the characters are us. Because of trying to be connected to reality on many levels we scanned ourselves and people we know. We wanted to have ordinary-looking people.

There are different civilians so we developed different personalities. Each time you start you may get a different group. By reading their bios you can start to get an idea of their personalities. You see if they're tough people or delicate people, someone who feels for others and empathises. You may find people trying to hurt a girl in a deserted supermarket. If you run away and you have an empathetic personality the character may feel bad about running away. The bio gets updated with your deeds.

They also have skills. One character might have bargaining skills so she's a good person if you need to trade. She's also a coffee drinker so if she's feeling sad you may simply cheer her up by finding a way to get her coffee. Some of them are smokers so they'll want cigarettes. Cigarettes are also a pretty good trading item. In Sarajevo, vodka was the best tradeable item because [it was desirable and useful] – people drank it to cheer themselves up and used it to disinfect wounds. To get weapons they would trade vodka to military in exchange for firearms. In the game you can make a moonshine still and, if you have the necessary components, distill vodka.

RPS: The characters each have different interpersonal skills but it seemed like everyone was able to craft items regardless of their skillset – is that true?

Pawel Miechowski: Yes. However, for example, if Bruno is a good cook he will use less resources to cook a soup and do it faster.

If I have enough components and electrical parts I can create a radio. With the radio I can not only listen to some music if I'm lucky and catch a signal but from time to time there is some news. You can figure out what people are trying to tell you to stay safe, for example. If there's an outburst of violence in the city it can make you aware of where that is.

RPS: Is the war still going on at this point of the game?

Pawel Miechowski: Yes. The city is under siege and some day the siege will be over. You don't know when because in reality no-one's going to tell you the war is going to end two weeks from now. But yes, it ends some day and your goal here is to survive.

The reason the game is not taking place in any particular siege is that we want to be totally away from any political meaning and also deliver the message that it can happen anywhere and at any time. When it happens it doesn't matter if you're English, Polish, Jewish, Arabic – you're a human and you need to survive. On a basic level we're the same humans.

Please keep in mind we are from Warsaw, Poland. Warsaw was heavily touched by the Second World War so most of us have grandfathers who survived heavy bombings and then the Warsaw Uprising. When the uprising was over in October '44 the city was completely ruined. People were trying to survive. They were called Robinson Crusoes of Warsaw. The other Pawel on our team, his grandfather was in Leningrad during the Second World War. The siege was so heavy and hard that actually there were acts of cannibalism in Leningrad. Pavel's grandfather doesn't really want to talk about [his experiences in the war] – he has some very bad memories – but he's also got some really thrilling stories.

RPS: Is there a tension there for you? When people have these experiences in real life they're so harrowing or fundamentally changing they're hard to even speak about but you're making a game...

Pawel Miechowski: We're thinking about it a lot. The game is not a simulator of atrocities, it's a take on how people struggle and what are their emotional challenges. We're fully aware this is an adult, mature game covering serious topics but there's a line. We decided firmly we're not doing a simulator of atrocities. If you're trying to be the bad guy in the game and killing everyone you meet or steal everything you can, sooner or later you will be punished. In war people were trying to stay human as much as they could so if you do evil things, empathetic personalities will suffer sooner or later.

RPS: How do the emotional effects manifest?

Pawel Miechowski: When sad, people will be more likely to refuse to do something – to craft or eat. If they're depressed they probably won't be doing anything unless you force them.

RPS: What do you want people to get out of playing This War Of Mine?

Pawel Miechowski: We want to raise awareness about how civilians suffer when war is breaking out. We want to show the other side. We're partnering with War Child so we're going to raise money for [kids in war]. From the perspective of being creators we use a parallel to movies because it works well in this case. Sometimes you're in the mood to watch an action movie or a comedy. Sometimes you watch drama – The Pianist or Saving Private Ryan with that brutal opening. We decided we see games as ready to speak about important things. We're not pioneers – we already have amazing games which do that really well – Gone Home, Papers Please.

RPS: Tell me more about the War Child collaboration.

Pawel Miechowski: They see it as possibly the best game to co-operate with because it's about suffering, not about shooting and running and having fun in war. There's a campaign – real war is not a game – so we will be trying to raise awareness of that as well.

RPS: In terms of what I've played of the game it hass only featured adults, are children part of the game too?

Pawel Miechowski: There are some situations in the game where there are children but they are not playable yet. We have ideas for future updates.

[Miechowski turns his attention back to the game on screen as he sends one of his characters out to scavenge for more resources]

Pawel Miechowski: The Steam community asked why jewellery was so – not worthless – but why it has low value. In war you need food – you can't do anything with jewellery other than trading it. In the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw there was a really horrible situation where the Germans killed everyone and people from the Polish side found a lot of dead bodies of hungry ill people and they had lots of jewellery with them – it was simply worthless.

RPS: What made you decide to get the player to manage a group of people rather than role playing as one character?

Pawel Miechowski: Because the connection between them matters. In some cases you will need one to help the other. They're also emotionally connected. If you go against their moral codes they may feel sad as well. In One Year In Hell and other cases people were telling us that living in a group is key – you won't make it as one. In a group it's easier but the group can't be too big because it would need a lot of medication and so on.

[We watch as Miechowski takes a character scavenging and finds an elderly couple still in their home. He punches them until they fall and takes their resources – it's really uncomfortable to watch and Miechowski repeatedly tells me this is for demonstration – he doesn't usually play like this. The effect on the group is marked. We check the bio of Pavle, the character responsible for the brutality. He thinks he did the right thing but he has still become depressed, he shambles about the base, defeated posture. The rest of the party are also saddened, although they appear to understand why Pavle would have done what he did]

RPS: Is it hard to playtest those scenarios?

Pawel Miechowski: As a developer you play all the possible situations and outcomes. Yet each time I do – theoretically it's just a non-existing collection of computer-generated bits, yet I don't feel good about it. During the development we were thinking that in movies and books you are spectator but if they're good stories you are able to feel empathy, love, hate with characters. With games you can do something that will make you feel remorse over what you did. So this is uncomfortable. If you do worse things you can feel the consequences of what you're doing.

This War Of Mine will be "coming soon" – the team will likely be announcing a prospective release date in the next few weeks.