Wot I Think: Undertale

I double-take when I see the sign on the front of the library. Something feels off, and I peer at the screen, and there’s definitely an extra letter that’s snuck in there somewhere. The little town of Snowdin is, as the name suggests, blanketed in thick snow, and the lights in the windows of the library look warm. Inside, the librarian looks up at me tiredly. “Welcome to Snowdin library,” she says. “Yes, we know the sign is mis-spelled.”

There is something irrepressibly charming about this.

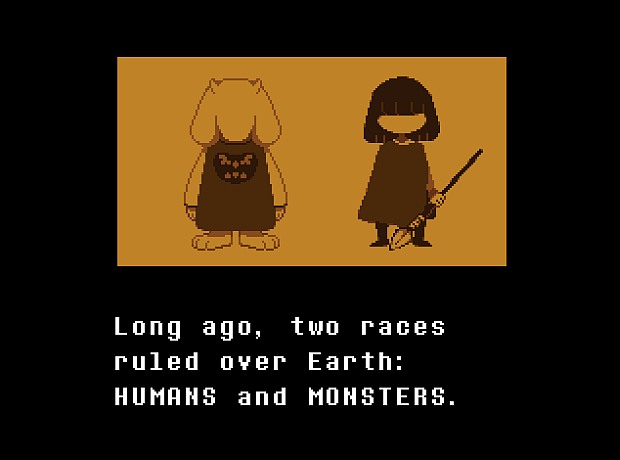

Undertale [official site], a game made mostly by Toby Fox, begins with a muted cutscene that feels immediately and deliberately evocative of The Wind Waker’s opening mural. “Long ago,” read the subtitles, “two races ruled over earth. HUMANS and MONSTERS.” And then there’s a little picture: a horned furry creature on the left and a cloaked human on the right. The human is holding a spear. The stage continues to be set with that particular blunt efficiency of the older Zelda games; there was a war, the monsters were defeated, they were sealed beneath the mountain. Years pass. A human child, the protagonist, climbs a mountain and falls down an enormous hole. Then the game begins.

It doesn’t take you long to realise that the opening cutscene isn’t quite giving you the full picture. See, down in the Underworld, myths and legends are incredibly important - they are the fabric of the monsters’ history - but equally important are talk shows and fast food and social networks and cinnamon and butterscotch pie. This is a game in which old legends are told powerfully and earnestly and, at the same time, people on ladders preparing a sign for a library make one small but important mistake.

I should say. Everything I have told you so far occurs very early on in Undertale’s story, and forms such a small part of what follows, but to talk about the game without spoiling anything at all would be very difficult. I’m going to be as absolutely judicious as I can, but if you want to go into this game completely cold, you should probably stop reading now. Actually, you should stop reading after this bit: Undertale is very, very good. Mostly.

The Underworld is filled with monsters, and while some of them very definitely know what they’re doing, most of them don’t really know what a human looks like, or what they should do if they encounter one. For them, humans are mythical creatures, simultaneously terrifying and unusual and as far as they’re concerned, a small child wearing a stripy shirt probably isn’t one.

The first major monster that you encounter is Toriel, though, and she knows exactly what you are. She takes you under her wing, and in a beautifully paced tutorial sequence, walks you through several puzzles in the ruins that she tends. Toriel’s all right. At one point, she begins to explain a puzzle involving a field of spikes and then gives up, takes you by the hand, and leads you through the safe path. Puzzles, she explains, are “ancient fusions between diversions and doorkeys” and as you continue your journey you encounter a large number of them.

Most of the time, though, and this is something I really appreciate about the game, the puzzles aren’t so much an opportunity to test your brain, but a chance to learn something about the world or its characters. In the same way that Portal 2 demonstrated that “doing something unusual involving portals” was just as interesting as “solving a puzzle room”, you’ll frequently begin a puzzle in Undertale only to find that the rules have changed dramatically, or it was never a puzzle at all.

The same is true for the game’s combat, which is utterly bizarre and entirely brilliant. Every fight in the game can be beaten non-violently, and the means for doing so are unique to whichever enemy you’re encountering. I suppose the best way to explain this would be to tell you about the time I met Woshua, who was very, very afraid of germs. He was holding a sponge. Whenever he tried to hit me, little drops of water danced across the screen, which I had to avoid in a sort of bullet-hell minigame. I could have walloped Woshua with a stick or something, but instead I went inside the “ACT” menu where several options presented themselves. I could “TALK” or “FLIRT” or “CLEAN ME” and when I suggested the last option, Woshua said “wosh ur leg” and I dodged some bits of soap flung in my direction. After doing this a couple of times, he was suitably happy with my lack of germs, and I was able to spare him via the “MERCY” menu. Most fights played out similarly, except sometimes enemies would take phone calls, or get bored, or engage in conversation, or make me answer multiple choice questions.

And it’s all so playful! It’s so playful. The game made me laugh out loud on several occasions but, more importantly than that, it understands that this particular style of comedy in games has to be more than just funny dialogue; it requires whip-smart control over player expectation and interaction, and an awareness of the game as a complete entity. More than any other game I’ve played, Undertale is filled with callbacks and brick jokes, each landing just as you’ve forgotten the setup and each delivered with the same care and certainty as the game’s mythology. To spoil any of these moments would be remarkably unfair, but they come again and again, beginning from almost the first line.

Earlier I said that the game was mostly very, very good and this is the point in the review where I should explain the “mostly”. I feel weird about this. In fact, I feel so weird about this that I finished the review, got ready to submit it, then sighed and opened it up again.

See, the opening two thirds of Undertale are so sparklingly good, so fizzing with creativity that it feels very distinct when the game moves into its last act and things go downhill a bit. They don’t go downhill a lot, but enough that when I travelled on a little boat and found myself back in Snowdin, I felt a sad nostalgia for the early game. There is a distinct tiredness felt in the late game, some of which I feel is narratively appropriate, but other parts of which simply feel like the designer beginning to run out of steam. The clever pseudo-puzzles from earlier in the game become actual, traditional puzzles, and the game’s penultimate environment is a repetitive labyrinthine space. The dialogue is still snappy and the characters are still interesting (a late game conversation in a restaurant with a recurring character is particularly memorable) but it feels as though something substantial is missing.

Part of me wonders if the game is simply a little too long, but that doesn’t quite feel right because even after it’s finished, there are still new depths to be plumbed and they’re great. There is a wealth of stuff that only begins to arrive on a second playthrough, much of it as fresh and startling as the best bits of the first. The issue is perhaps that of pacing, then; in moving into the final act, the game loses its way a little, before picking up steam for the ending and subsequent playthroughs.

I don’t want to say that it leaves a sour taste in my mouth, but it does, just a little. When I restarted the game and saw how the world had shifted, I was reminded of how virtuosic the game can feel at its best, and I began to reconsider my thoughts on the final act. But it would be dishonest of me to say that Undertale was a game which, when I completed, I felt entirely in love with. Perhaps you’ll feel differently, and the game is such a strange and clever thing that I suspect you will. Perhaps, and this is equally plausible, the choices you make over the course of the game will cause you to see the game’s events in a different light.

There are other, smaller problems. The (largely enormously entertaining) boss fights tend to run a little long, and often travelling the distances between the bosses and a source of health replenishing items requires a trudge. But - and I’ve really given this some thought - I can still recommend the game. When it reaches its heights, it is startlingly good, and even at the worst of its lows it still manages to surprise.

The soundtrack bears mentioning. It’s enormous and varied, dropping in and out of pastiches of various styles, proving itself as playful and versatile as the writing. The game is clearly aware of this, too - occasionally during fights you’ll see things like “all the spiders clap along to the music” and you’ll think to yourself “yes. And so do I.” It’s catchy, too, but in the memorable way rather than the irritating one. I legitimately found myself whistling one of the boss themes under my breath as I wrote this, and it’s been quietly running alongside my day-to-day since I heard it.

Before Toby Fox made Undertale, he created an astonishingly complicated ROM hack of Earthbound and, in his brilliant description of how he managed it, he mentions creating the trailer. “It was a trailer pretending that a funny game was scary,” he writes, “In reality… it was actually a trailer for a scary game that pretends to be funny.” Sometimes Undertale feels a little like this. The ending especially, which I won’t talk about in detail, draws threads together from throughout the game and moves into a finale that is by turns tragic and funny and comprehensively terrifying, and could very easily turn the game into something scary “that pretends to be funny”.

But I don’t know if that’s the case. I think about Toriel guiding me through those early rooms, about the quietly austere opening cutscene, about “ancient fusions between diversions and doorkeys”. The brilliance of Undertale, its delicate balance that it manages for most of the time you'll spend playing it, is that it understands how to be scary and funny all at once. Inside the Snowdin library there are leather-bound books that contain strange prophecies, books that say profound and disconcerting things about the human soul.

Outside, the sign has been mis-spelled.

Undertale is out now on Steam or direct from the developer.